The Woman Who Saved Emily Dickinson's Poetry

It might have seemed a no-brainer that Emily Dickinson would be a widely published and recognized poet in her native Amherst, Massachusetts — after all, her paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was well known in the community as the founder of Amherst College (via Biography). Although she was a gifted and talented student, Dickinson left her academic life and retreated to a life of solitude. Little is known of exactly why the future poet would become a social recluse; some speculate it was due illness or social anxiety.

Although posthumously she is considered one of America's best and most prolific writers, Dickinson was secretive about her poetry during her life. Perhaps that gives some context to her poem "Success is counted sweetest," which begins, "Success is counted sweetest / By those who ne'er succeed. / To comprehend a nectar / Requires sorest need" (via Poetry Foundation). Notably, this poem was one of only 10 that Dickinson had published in her lifetime; she was not a complete unknown in the writing world (via Britannica).

Dickinson would eventually find success, just not necessarily during her lifetime. And one woman managed to break through to the Dickinson family just enough to shine a light on the poet's talent.

A breath of fresh air

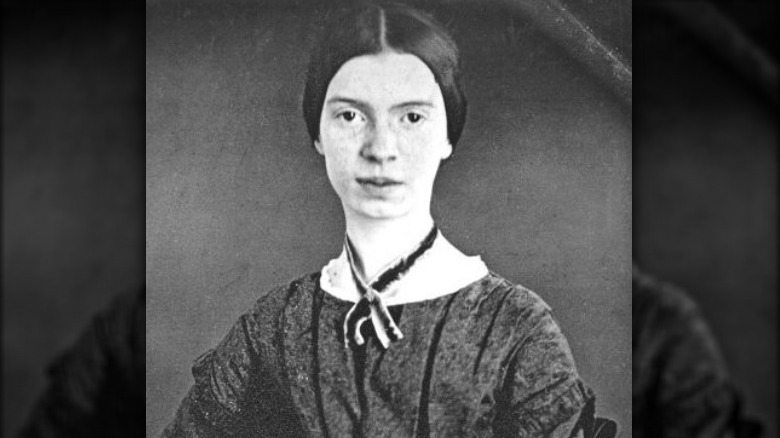

Known for being extroverted, pretty, and full of life, Mabel Loomis Todd studied piano and voice at the New England Conservatory in Boston (via Emily Dickinson Museum). She was also a skilled painter and had several of her own short stories published. Originally from Washington, D.C., Loomis came to Amherst with her husband, David Todd, an astronomy professor, in 1881. We know from a letter to Todd's mother that Emily Dickinson (above, left, with her siblings) was known as a town recluse. Emily's brother and sister, Austin and Lavinia, invited the entertaining Mrs. Todd to their family residence to play and sing for Emily and their ailing mother. Emily and Mabel struck up a strange friendship that would last until the poet's death. The Dickinson brother, who was married, had his eye on the young and outgoing Mabel, so his invitation might have been more in the romantic sense than out of genuine concern for his sisters and mother who lived next door to him.

Emily and Mabel only communicated via notes between rooms even as Mabel was performing in the house. The musician was not permitted to see Dickinson's face for reasons not entirely known. Mabel, who would eventually have an affair with the much older Dickinson brother, wrote (via New England Historical Society), "It was odd to think as my voice rang out through the big silent house that Miss Emily in her weird white dress was outside in the shadow hearing every word." Sometimes Dickinson would send in poems from the other room.

She could not stop for death

To say that Austin Dickinson's wife was not thrilled about the frequent visits to her in-laws' residence next door is an understatement. She was filled with jealousy towards her husband's mistress. And rightly so; Mabel (above) carried on a steamy romance with Austin for 13 years.

Emily Dickinson died at the age of 55 of heart failure in May of 1886 (via Biography). Her sister, Lavinia, found hundreds of poems and reached out to her sister-in-law, Susan, to have them published (via Emily Dickinson Museum). Susan had now soured on the entire Dickinson family and didn't exactly hurry to help fulfill her sister-in-law's request. Tired of waiting on Susan, Lavinia stole the poems back and gave them to Mabel, begging her have them published on her Emily's behalf.

Although she found the situation to be precarious, Mabel spent nine years transcribing and editing hundreds of Emily's poems into three volumes of work. For this task, she enlisted the help of one of Emily's friends in life, Thomas Wentworth Higginson. A graduate of Harvard Divinity School and a Unitarian minister with connections to The Atlantic Monthly magazine, Higginson helped get some of Emily's early work published when she was 31, and the two remained friends for the rest of her life (via Emily Dickinson Museum). Together, Higginson and Mabel made small changes in punctuation and some rhymes. At other times, they created titles that would attract 19th century readers.

Mabel Loomis Todd helped shape history's view of Emily Dickinson

Marketing-wise, Mabel delivered lectures on the strange and unusual life of Emily Dickinson at Amherst and to this day, her words continue to shape the lore around the reclusive poet. Additionally, Mabel worked to publish Emily's many letters in a two-volume series.

When Austin Dickinson died in 1895, tensions were high between his wife and Mabel. After having lost a lawsuit over a disputed land inheritance, Emily's advocate retaliated by locking away Emily's poems and letters to keep them from the Dickinson family. Mabel decided to pursue a life of lecturing around the northeastern United States and to spend more time accompanying her husband on eclipse missions around the world. She also went on to found organizations such as The Amherst Historical Society. When Mabel had a stroke in 1913, she and her husband moved to Florida. Emily's niece took over remaining publishing duties and donated what remained of the poet's work to Amherst College.