Why A NASA Astronaut Pranked Everyone With A Fake Cockroach

NASA's space expeditions aren't the sort of environments in which one expects to find practical jokes and childish pranks, but perhaps in November 1969, everyone was feeling a bit more relaxed and in the mood for jokes. After all, the organization was coming off the massive success of the Apollo 11 mission just under four months earlier. In July 1969, the United States landed a spacecraft on the moon and astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on its surface, followed closely by Buzz Aldrin, per the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Apollo 12's mission employed Commander Charles "Pete" Conrad, Lunar Module Pilot Alan Bean, Command Module Pilot Richard Gordon...and possibly a tiny stowaway who eluded NASA's pre-flight attempt at capture.

In a YouTube video produced by the Kennedy Space Station Visitor Complex, Apollo Spacecraft test team project engineer Bob Sieck and manager Ernie Rayes relayed the preparation of Apollo 12's spacecraft pre-launch. Per Rayes, "One of the quality guys was doing the final closeout look and said 'Hey guys. I just spotted a roach.'" Rayes joked that he couldn't have seen a roach because no one would have given him the badge necessary for entrance. A test conductor told Sieck they couldn't use chemicals to exterminate the insect because it would harm the interior of the ship. An attempt to catch the roach via sticky paper and bait proved unsuccessful, and the spacecraft became known to the test team as the "roach coach" and the "cucaracha."

One very small step?

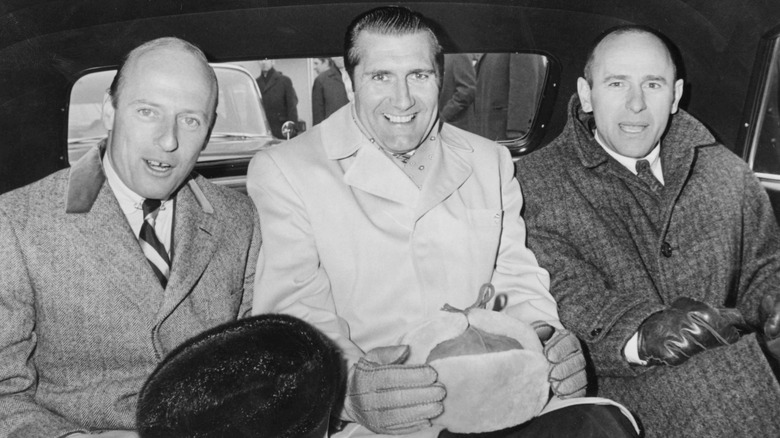

The mystery of the missing roach was the last problem to be cleared before approving Apollo 12 for launch. The cockroach remained hidden and it's entirely possible that the insect flew to the moon alongside Pete Conrad, Richard Gordon, and Alan Bean (shown above). Conrad referenced the stowaway during a televised press conference held with the crew during their return to Earth, holding up a piece of paper with a roach taped to it, as reported by How Stuff Works.

In NASA's transcript of the commentary from within the spacecraft during Apollo 12, page 907 features Conrad asking for George Low and telling listeners "He sent us a letter about not having a certain passenger aboard the spacecraft...and we just wanted to show it to George so that he could write the proper letter to allow him to have made the flight." When someone on the ground responds "You found him, huh?" Conrad responds in the affirmative and jokes that the roach was in the food locker and is "very fat."

According to Jonathan H. Ward's 2015 book "Countdown to a Moon Launch," Conrad had smuggled a plastic roach onto the ship with this very prank in mind. Per the Lunar and Planetary Institute, the mission was a success amid the roach concern and subsequent jokes. Conrad and Bean performed two moonwalks, during which they installed several instruments to be used for multi-year experiments and collected 75 pounds of sample material from the lunar surface.

Pete Conrad loved pranks

The United Kingdom's National Space Centre once referred to Pete Conrad as "the ultimate astronaut prankster," noting that upon becoming the third person to set foot on the moon, he referenced Neil Armstrong's famous "one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind" line and yelled "Whoopie! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me." This reportedly won Conrad $20 in a bet concerning whether astronauts' moon speeches were written ahead of time or recited on the fly. At one point, Conrad was actually declared "not suitable for long-duration flight" thanks to his penchant for mischief, which included gift-wrapping a stool sample and leaving it for a supervisor. Even after he calmed down enough to be permitted to go into space, he continued his shenanigans, making up a code so astronauts could secretly tell each other racy jokes, and discussing an entirely fictional astronaut named Walter Frisbee with reporters.

Per his 1999 obituary in The New York Times, Conrad went on four space missions and spent a total of 49 days, 3 hours and 37 minutes in space, which set a record at the time. He set another record when he endured a total of 28 days on Skylab. He retired from NASA in 1973 but continued his interest in space, even predicting a future in which space tourism became commonplace. He died from injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident on July 8, 1999. He was 69 years old.