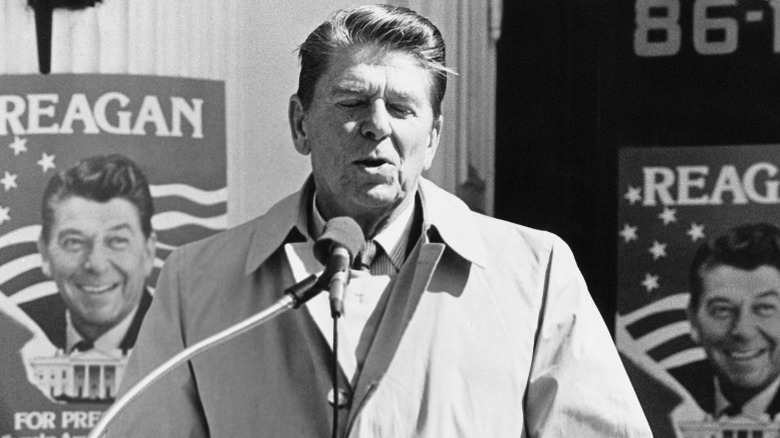

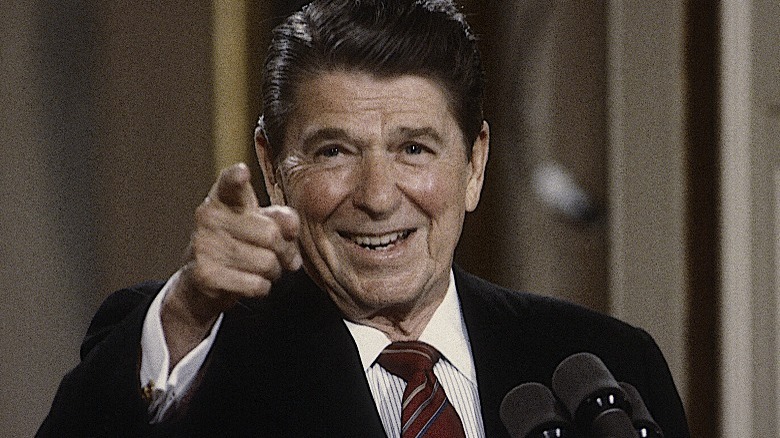

Questionable Things About Ronald Reagan's Presidency

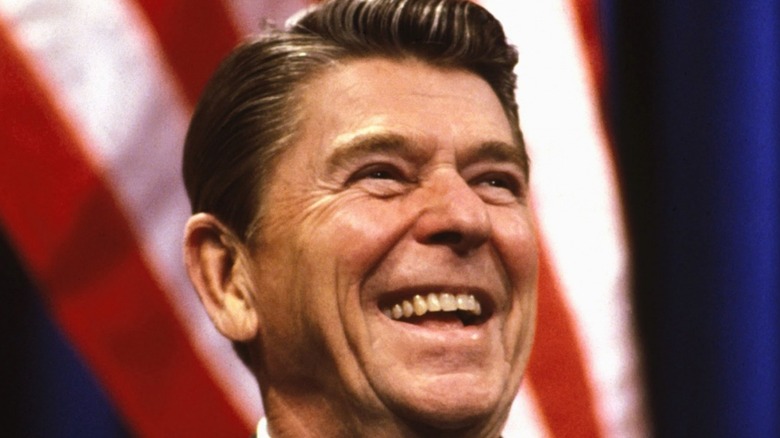

Though Ronald Reagan left office over three decades ago in 1989, he is still one of the most well known and popular presidents. Republicans today still see him as one of the best presidents in history and still champion his ideals on the campaign trail (via the Miller Center). Reagan was incredibly popular during his presidency, winning reelection in 1984 by getting 49 out of 50 states in the electoral college. Many people give him credit for helping the United States "win" the Cold War against the evil empire of the Soviet Union, and his political legacy towers over the executive office decades later.

However, Reagan's legacy is not free from criticism by a long shot. His economic policies led to an increase in trade deficits and the national debt, while tax rates for the wealthiest tax bracket were reduced by over 40%. His foreign policy in the Middle East resulted in one of the most infamous presidential scandals in American history, though his administration managed to survive. These are the most questionable things about Ronald Reagan's presidency.

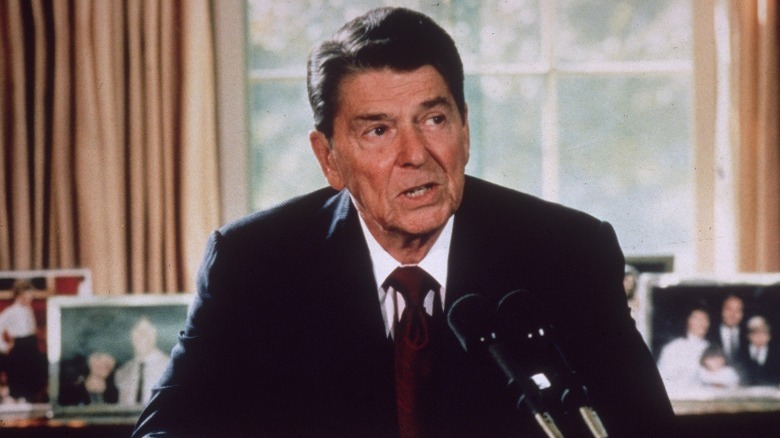

Allowing weapons to be sold to Iran

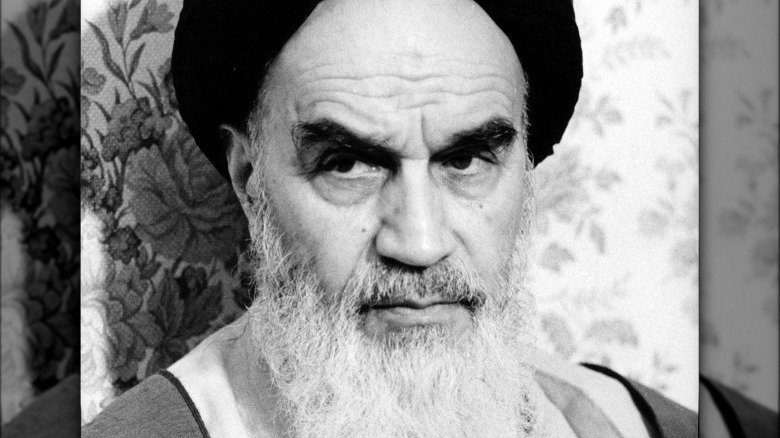

One of the most damaging scandals during the Ronald Reagan presidency were the revelations that his administration secretly organized arms deals between the Israeli and Iranian governments in the mid-1980s. According to John Prados in "Safe for Democracy," the ordeal stemmed from the kidnapping of numerous American citizens in Lebanon in 1984 by Shiite terrorists. The White House knew that the Shiites were controlled partly by the Iranian government, but the CIA initially threw cold water on any plans for cooperation with the Iranian Ayatollah Khomeini (pictured above).

That was until April 1985, when the National Security Council (NSC) found out that the Iranian government wanted to buy various weapons from the United States. It would have been political suicide for Reagan to openly sell the Iranians weapons just a few years after the Iranian Hostage Crisis, but soon a deal was worked out where the Israeli government would instead sell the Iranians weapons with American approval. The White House approved the program on August 8, 1985, which involved the release of American hostages at the same time.

Eventually, three U.S. hostages were released in exchange for more than 2,000 missiles of various types and spare aircraft parts. However, four more Americans and a British man were also kidnapped, and a CIA agent who was being held hostage in Lebanon died. The scandal broke in 1986, first in Lebanon and then in the U.S., severely damaging Reagan's credibility and image.

Illegally funding the Nicaraguan Contras

In 1979, a Marxist government came to power in Nicaragua called the "frente sandinista de liberación nacional" (FSLN), more commonly known as the Sandinistas (per "Safe for Democracy"). Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan's predecessor, immediately authorized the beginning of a covert action program aimed at taking out the Sandinistas and their Marxist government.

When Reagan took over in 1981, he quickly approved a $19 million plan to arm and train a group of Nicaraguan rebels, known as contras, to foment insurrection against the Marxist Nicaraguan government. However, in 1984, after roughly $80 million in CIA support had been given to the contras, the U.S. Congress actually stepped in and blocked any more funding. This was a blow to Reagan who was using Green Berets to train the contras, but his administration soon came up with a plan to circumvent Congress.

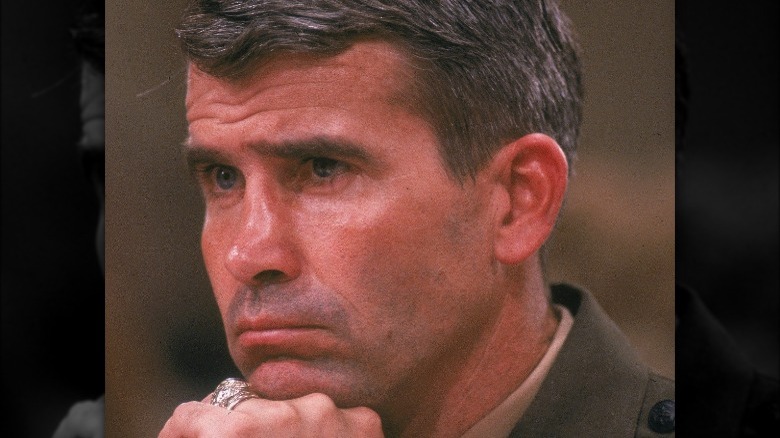

First, Reagan got the Saudi Arabian government to start giving the contras tens of millions in aid, then, an NSC staffer named Oliver North came up with the idea of using money from the Israeli-Iranian arms deals to finance the contras. However, after the Iranian arms deal leaked to the press it was only a matter of time until the link between that and the congressionally circumvented funding of the contras emerged (per Brown University). An investigation into the matter criticized Reagan and the White House for their conduct. Eventually, 14 people were charged in the affair, resulting in multiple felony convictions.

Mining the Nicaraguan coast

In April 1984, while the Reagan administration was waging their secret war against Nicaragua, a damning report was published in the Washington Post. The Post reported that the CIA had gone about placing underwater mines around the Nicaraguan coast to "harass and discourage shipping." This resulted in several commercial ships being damaged when they unknowingly ran over the mines.

The Post reported that the mining was done "probably with the general knowledge of President Reagan," and that it had been done without any forewarning given to Congress. The Post further linked the CIA with the contra rebels, reporting on their extensive contacts and $21 million in funding. Joe Biden, a Senator at the time and member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, spoke out about the funding of the contras, saying he opposed further funding of both them and the corrupt El Salvadoran government.

It turns out the Post was right. As shown in "Safe for Democracy," Reagan had been informed about the mining operation, and he approved it. Nicaragua sued the U.S. in the International Court of Justice over the mining two days after the Post report. The court ruled the Reagan administration's actions were illegal, but Reagan refused to acknowledge the ruling or remove the mines. The revelations about the secret mining led to massive amounts of domestic criticism, as well as the congressional blockade of contra funding, which eventually led to the Iran-Contra affair.

His disastrous Lebanon policy

In 1982, the Reagan administration entered U.S. troops into the ongoing Lebanese civil war, and it had predictably horrible results. As written in "Crisis and Crossfire," in the midst of the war, Israeli troops were battling militant factions of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and had invaded the capital city of Beirut. After a ceasefire broke down in June, Ronald Reagan had first introduced troops to help the PLO evacuate and broker a peace treaty between Israel and Lebanon. However, that far from ended any fighting.

Journalist Thomas L. Friedman was reporting from Lebanon at the time, and he wrote about his experiences in the book "From Beirut to Jerusalem." Friedman argues that Reagan's quick withdrawal of the Marines after the PLO evacuation led to a massacre of Palestinians in Beirut, which necessitated the Marines' return barely two weeks later. Reagan placed 1,200 Marines onshore to try and act as a "stabilizing force," but they quickly found themselves fighting in a war. In early 1983, a suicide truck attack blew up the U.S. Embassy in Beirut and killed 63 people. A few months later, another suicide truck attack killed 241 Marines.

With his tail between his legs and reelection in his eyes, Reagan soon withdrew the Marines from Lebanon for a final time, culminating his disastrous policy in the country. For the price of 300 lives, Reagan merely inflamed tensions in Lebanon and deepened anti-American fervor in the Middle East.

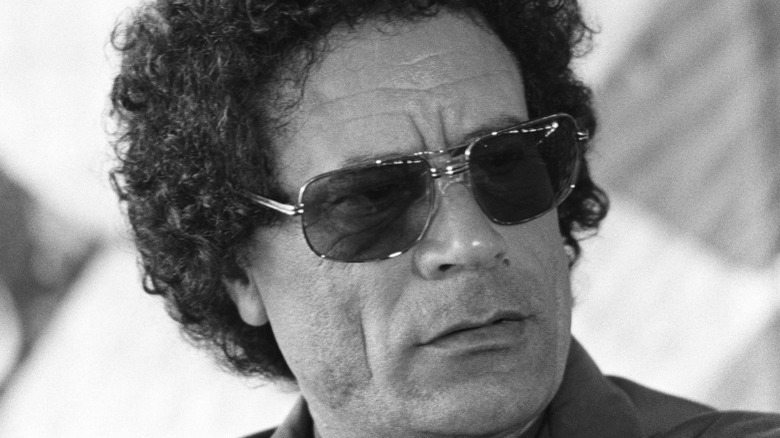

Intervening in Libya

One of the preeminent sponsors of international terrorism in the 1980s was former Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi (via "Crisis and Crossfire"). In 1981, Ronald Reagan decided to take a stand against Qaddafi that almost ended in disaster. He stopped importing oil from Libya and also ordered the U.S. Navy to start patrolling near the Libyan coast. After a couple of Libyan jets fired on the Navy, they retaliated in kind, downing both of them. Luckily, the U.S. didn't end up getting involved in a war in Libya, but Qaddafi started to increase his level of support for anti-U.S. terrorism.

Five years later in 1986, Reagan brought the Navy back to the Libyan coast, where they once again were fired on by Libyan forces. The Navy took aim at Libyan radar sites and patrol boats, destroying many of them. In response, Qaddafi ordered the bombing of a nightclub in West Berlin because of its popularity among U.S. servicemen. There were dozens of casualties in the bombing, and Reagan ordered a bombing campaign in Libya which almost killed Qaddafi.

While Qaddafi's appetite for financing terrorism diminished, international public opinion came down very hard on Reagan. Many criticized his administration's actions during the entire fiasco, especially when it came out that some of the U.S. bombs had gone off track and killed innocent civilians. Furthermore, Qaddafi retaliated in 1988 by bombing a civilian airliner that killed nearly 200 Americans.

Purging Social Security rolls

Starting in late 1981, the Reagan administration started purging over 100,000 people from the disability rolls of Social Security (as reported by The New York Times). As Brent Hull shows in his article for The Progressive Magazine, part of this was from existing policies started before Ronald Reagan, but the purging was exacerbated by a newly adopted policy under his administration that re-evaluated the benefits for many recipients.

As The Times reported, critics of the administration argued that many of the people being removed from the rolls were done so "arbitrarily and illegally" due to an "overzealous" administration. They pointed out the high proportion of those with mental disabilities, and the head of the Social Security program even admitted that "some people who are entitled to benefits are losing their benefits." Judges agreed, and by June 1987, 63% of people who had filed appeals over losing their benefits had gotten them restored (per the Chicago Tribune). In the interim, several people had fallen on hard times after having their benefits cut off, and a former Social Security analyst claimed that the Reagan administration was "oblivious to the pain it was causing deserving beneficiaries."

The Times reported again in 1992 about lawsuits that were still going on due to the Reagan administration's "systematic campaign to purge the Social Security disability rolls." As Hull noted, the policy was eventually ruled unconstitutional in 1986 by the Supreme Court.

Vetoing the 1988 Civil Rights Act

While it is mostly forgotten today, in 1988, Ronald Reagan vetoed a monumental piece of Civil Rights legislation. The legislation was the 1988 Civil Rights Restoration Act, which was meant to broaden Civil Rights regulations that had been diminished due to a 1984 court decision (argues "American Civil Rights Policy from Truman to Clinton: The Role of Presidential Leadership"). Reagan vetoed the legislation when it initially passed due to several concerns. It was the first time in more than a century that a Civil Rights bill had been vetoed, with the previous one coming courtesy of Reconstruction-era president Andrew Johnson (via Politico).

He was concerned that the bill augmented the federal government's power by "dramatically expanding the scope of federal jurisdiction over state and local governments and the private sector" including houses of worship and farms. Another issue Reagan had with the bill was he thought it was "a particular threat to religious liberty." Reagan had previously not supported Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s as the governor of California or in 1984 as president.

Unfortunately for Reagan, both the House and Senate overturned his veto in less than a week. The Senate had six more votes than needed to override the veto on a vote that split the party in half, and the House overwhelmingly overrode Reagan's veto by a margin of 159 congressmen.

Increasing the War on Drugs

One of the most unfortunate legacies of Ronald Reagan's presidency was his dramatic escalation of the War on Drugs. As the Drug Policy Alliance shows, the War on Drugs had started in the early-1970s during the Richard Nixon presidency. By the 1980s, the wider public was beginning to pay attention to the ongoing drug addiction epidemic that was plaguing the country. When Reagan was just beginning his second term, less than 10% of the country felt drugs were a serious problem, but within four years, that had exploded to a whopping 64% of Americans believing drugs were the "nation's number one problem."

Much of this was due to media coverage of the cocaine and crack epidemics that were ripping apart the inner cities. As a response to increasing illicit drug use and crime, Reagan announced the "Just Say No" campaign aimed at stopping youth drug use. During his second term, in 1986, he helped Congress pass a landmark piece of anti-drug legislation — which has been heavily criticized since (per History).

One of the most controversial aspects of the bill is that it introduced mandatory minimum prison sentences for specific drugs. Many saw this as racist because of the disparities in sentencing it created that seemed to target Black Americans instead of whites. Prison rates skyrocketed due to the legislation, and prisons are where the effects are still being felt most prominently today.

Ignoring the AIDS crisis

Another tragic legacy of Ronald Reagan's presidency was his administration's handling of the AIDS crisis. As History explains, the crisis began in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the early-20th century, but it was not until the Summer of 1981 that it became an epidemic in America. It broke out within the gay male communities of Los Angeles and New York, alarming health officials who were unsure of what was going on.

Unfortunately, public reaction to the AIDS crisis in America was incredibly shameful. The gay community was unfairly stigmatized and ostracized by outsiders, and within the community there was widespread fear about contracting the disease and dying. Just having AIDS was enough to label someone as gay back then, at a time when federal protections largely did not exist regarding gay rights.

Reagan's administration was incredibly callous and unsympathetic to those affected by the disease, ridiculing it as the "gay plague" and laughing about it during press conferences. Reagan himself refused to even publicly mention the word for years until 1985. The government refused to increase funding for AIDs research even though there were already thousands of deaths. It wasn't until a close friend of Reagan died that he started to push for federal increases for AIDS research. In 1987, Reagan started to take the crisis even more seriously, but by then nearly 50,000 people had already been infected, and many had died.

The failed Strategic Defense Initiative

While Ronald Reagan is often credited with helping end the Cold War, not all of his defense schemes targeting the Soviet Union paid off. One of the most maligned and criticized was his 1983 initiative known as "Strategic Defense Initiative" or SDI. As shown in "The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917-1991," SDI was a defense scheme whereby "space-based weapons, including beam and particle weapons, lasers ... would attack Soviet ballistic missiles" that were being fired at American targets.

The initiative was immediately ridiculed by critics who nicknamed it "Star Wars" as an ode to the movie which had recently come out. Reagan claimed the plan was going to be an effective deterrent and that it would also bleed the Soviets dry economically by forcing them to spend more on defense. Critics countered by pointing out easy ways for the Soviets to circumvent any potential system, and argued that it was actually the Soviets who could use the program to their economic advantage.

In the end, it was the critics who were right, as the fledgling program never took off. Most components, like the famous x-ray laser, didn't work — even after $17 billion in funding. The administration even rigged a public test of SDI to try to prove it worked, which convinced no one and only made the whole scheme more pathetic.

Playing both sides during the Iran-Iraq War

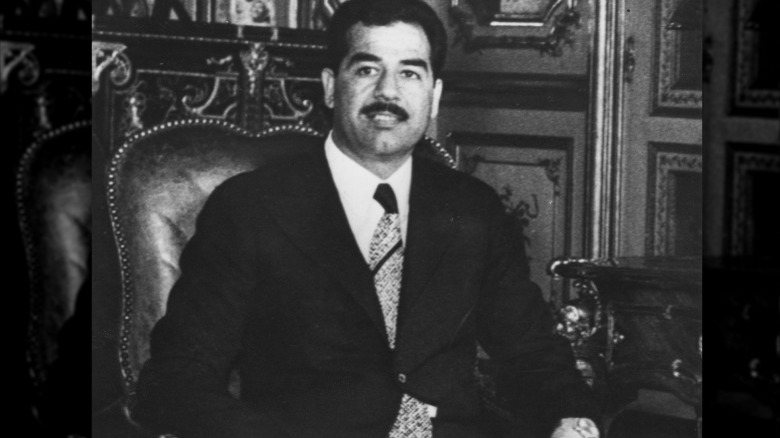

The name Saddam Hussein is one of the most reviled and hated in the United States. Yet, for a brief period in the 1980s, Ronald Reagan had another term for the ruthless dictator: customer. For most of the 1980s, Iraq was fighting their neighbor to the west, Iran, in a brutal and bloody war (according to "The Cold War"). The U.S. was incredibly hostile to Iran at the time over the recent 1979 Iranian Revolution and 1980 Iranian Hostage Crisis, where dozens of Americans were kidnapped and held for ransom.

While publicly Reagan claimed the administration was neutral in the war, they quickly started subsidizing the Iraqi government with economic aid and arms. However, at the same time they also started providing Iran with weapons during the Iran-Contra scandal. For nearly a decade, the Reagan administration fed the Iran-Iraq war by providing arms to each side.

In 1987, the administration started to seriously work to promote an end to the war, but Iran refused to comply. Amid increasing tensions in the Persian Gulf, U.S. forces in the area accidentally shot down an Iranian civilian aircraft, killing almost 300 people. Eventually the war ended in 1988, but only after incredible amounts of casualties. While the Reagan administration certainly isn't to blame for the war, its policies exacerbated the conflict and provided more firepower for the bloodshed.

The Reagan Doctrine

Ronald Reagan's foreign policy for his second term was widely known as the Reagan Doctrine. Yet, as shown in "The Cold War," the "principal intellectual support" for the doctrine was actually given by his ambassador to the United Nations, Jeanne Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick argued that "authoritarian" and "totalitarian" governments were inherently different from each other, and that the U.S. could work with authoritarian governments. She claimed that they could be persuaded to eventually commit to democratic reforms — just so long as they weren't communist.

By following Kirkpatrick's ideals, the Reagan Doctrine found itself mixing with some pretty tricky bedfellows. The administration openly sided with racist and violent regimes like those in power in South Africa, El Salvador, Chile, and Pakistan. In particular, Reagan pressed hard for Congressional approval to aid the El Salvadoran government, a government that murdered 60,000 civilians through roving death squads during a six-year period that coincided with Reagan's entire first term.

In many cases, like in the Philippines and Haiti, Reagan's support for corrupt regimes only ceased when he thought their government might be overthrown. Until then, he was perfectly content to keep funding them, regardless of their human rights records.