The Untold Truth Of The Commonwealth

Of global institutions, the Commonwealth of Nations is one of the most peculiar. Consisting of dozens of independent countries, the only thing that almost all of them have in common is that they were once part of the British Empire. These countries have maintained ties in the form of the Commonwealth, a consensus-based international association.

Ostensibly, the Commonwealth of Nations was formed as a way to advance all countries that are members. In a way, they emulate the United Nations through declarations of human rights, backing peaceful multilateral solutions, fighting climate change and promoting democracy.

This sounds good, but the Commonwealth has vociferous critics, such as British writer Afua Hirsch, who wrote an opinion article in The Guardian in 2018 deriding the Commonwealth as "Empire 2.0." Hirsch asserted it was ineffective and did little to help its members, especially nonwhite states. Then there is a question as to whether or not it's even relevant. In her argument, Hirsch quotes Philip Murphy, Director of History & Policy at the Institute of Historical Research in London, who said the Commonwealth was "an irrelevant institution wallowing in imperial amnesia."

So the Commonwealth is a bit more complex than it appears on the surface. Let's take a look at how the Commonwealth came into being and what are some of the untold truths behind it today.

The Commonwealth grew out of a fading empire

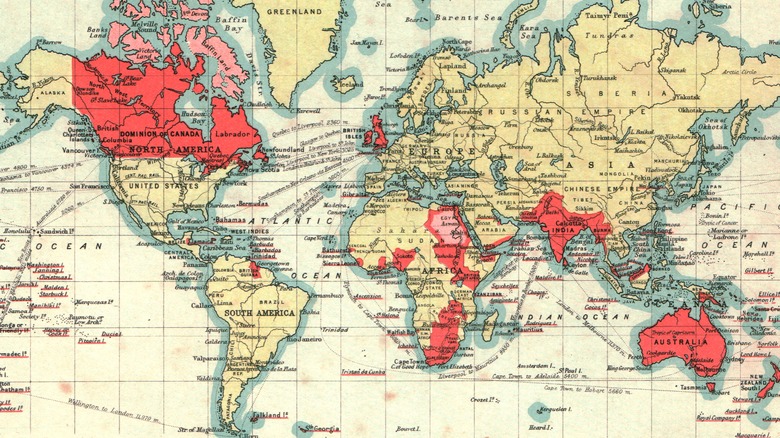

The British Commonwealth was officially established in 1931, but its history goes deeper. National Geographic explains that in the late 1800s, the British Empire had reached its zenith. Britain controlled approximately one-fifth of the world's land territories and dominated over diverse peoples ranging from India to Canada to Africa. The building of the empire took centuries, but it reached its greatest rate of expansion in the 19th century under Queen Victoria. It's telling of where Britain was going at the time when in 1877, Victoria was named Empress of India. The size and scope of the empire were summarized by the popular saying, as recorded by World Atlas: "The Empire upon which the sun never sets."

This was no hyperbole, and as the empire grew, so too were the seeds laid for its eventual disintegration. A world of far-flung colonies was hard to manage and the various dependencies, realms, and territories under the British yoke came to believe that it would be far more effective for them to govern themselves.

Canada started the Commonwealth

The Commonwealth really begins in Canada. By the mid-19th century, there were fears that Canada would be dominated by, or even annexed, by the United States. These fears, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, became exacerbated after the American Civil War when Canadians were shocked by the conflict. As a result, there was mounting pressure by Canada upon Britain to grant them greater autonomy as a united colony. The result was that in 1867, the Dominion of Canada was created.

As National Geographic points out, dominion status imparted self-government to Canada but with British imperial veto power. This was the first step in loosening the bonds of empire and thus establishing the Commonwealth as we know it today. In the decades that followed, other territories such as Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa, all achieved this status. It's notable that all these dominions were predominantly white territories. Nonwhite colonies remained strictly tied to the imperial yoke.

World War I pushed the Commonwealth into existence

While self-governance was in effect for a handful of colonies by the eve of World War I, the situation changed drastically by the war's end. One of the political principles upon which the war was fought was self-determination, which Britannica explains is allowing people who have a national consciousness to govern themselves.

British colonies latched onto this concept and could point out the hypocrisy of a country that fought for those high-minded principles still maintaining an empire over those who wanted to rule themselves. The UK's National Archives notes that the next step was to grant greater autonomy to the dominions in a new "mandate" status. Meanwhile, a greater clamor for independence from other territories grew, particularly in India, where violence over their independence mounted.

By 1926, the push for equality among the dominions was great enough that they were acknowledged to be of equal standing to Britain. This was formalized in 1931 with the Statute of Westminster, which established what was then called the British Commonwealth of Nations. The first members of the Commonwealth were (per National Geographic) the UK, Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Then after World War II, it became apparent that the British Empire would no longer hold. In 1949, through the London Declaration, those countries already within the Commonwealth opened up membership for all, and the political association renamed itself the Commonwealth of Nations. Many newly independent states chose to join in the years that followed.

The Commonwealth is marked by a common past of colonization

The common denominator of the Commonwealth is that for the most part, it comprises territories that had been part of the British Empire. According to Britannica, in the immediate years after the passage of the Statute of Westminster, membership in the Commonwealth was limited to only those countries that swore allegiance to the British Crown as the titular head of state. For example, India and Pakistan originally entered the Commonwealth upon their independence in 1947. However, when they moved to become republics in 1949, this meant that they would have to leave the Commonwealth. To allow them to stay in the Commonwealth the rules were changed under the London Declaration.

So without the allegiance requirement, it seems that the only thing holding the Commonwealth together was an imperial oppressive past. Despite this dark genesis, it seems that joining the Commonwealth was the thing to do in the mid-20th century. Dozens of countries joined the Commonwealth from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Some Commonwealth countries have their own monarchs

There are different classifications of Commonwealth countries. According to National Geographic, a Commonwealth country that recognizes its head of state as the British monarch is considered a "Commonwealth Realm." This includes countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, which have historically had the closest ethnic and cultural ties to the United Kingdom. Yet it also includes some other countries, such as Belize in Central America, the Bahamas, and the tiny island country of Tuvalu. In total there are 15 Commonwealth Realms, including the United Kingdom itself.

In truth, having the British monarch as your head of state is not a permanent thing. Some nations may decide on their own to remove the monarch and just remain in the Commonwealth. The most recent example of a country giving up the monarch is Barbados, when on November 30, 2021, it abolished monarchy. There was no revolution. Heck, the BBC reported that Prince Charles (now King Charles III), attended the event marking the changeover and Queen Elizabeth II sent her best wishes.

To make things even more confusing, there are five countries in the Commonwealth that have their own separate monarchs. Brunei, Swaziland, Lesotho, Malaysia, and Tonga all have their own monarchies of which all are constitutional or with very limited monarchical powers.

The British monarch is not the guaranteed head of the Commonwealth

Even though all the countries of the Commonwealth have different governments and some recognize the British monarch while others do not, the Commonwealth itself has a titular head. And this happens to be the British monarch.

However, there are a couple of caveats. The first is that the role is ceremonial and symbolic. The second is that the job is not hereditary. The member countries need to discuss and decide who is the Head of the Commonwealth.

Despite the second caveat, in 2022, upon the death of Queen Elizabeth II, her son, King Charles III, will succeed her as the head. This was the doing of the queen herself, according to The Guardian. In 2018, she gathered the leaders of Commonwealth countries to a retreat at Windsor Castle, whereupon she informed them that it was her "sincere wish" that he succeed her.

And who could refuse Queen Elizabeth? The decision was unanimous. Whether Charles' son, William, the Prince of Wales, will succeed him remains to be seen.

The Commonwealth is huge

While the Commonwealth has been criticized for being largely ineffectual, it does have the virtue of being big and growing bigger. There are 56 sovereign countries that are currently part of the Commonwealth. This represents 2.5 billion people of which most are young, averaging about 26 years in age. The majority of these countries (32 at last count) are actually small population-wise; that is, with a population of under 1.5 million. The smallest member happens to be Narau with a population of some 10,000, while the largest — with a whopping population of 1.2 billion — is India.

Despite population differences, each country in the Commonwealth has, at least technically, an equal say. It's probably because of its small country-skew that the Commonwealth is particularly interested in issues such as mitigating climate change since that would have more of a direct and dramatic impact on these areas. Also, the members tend to have more open trade with each other. While there are no formal trading agreements, the Commonwealth claims that it costs about 21% less to trade between Commonwealth countries than others. It's unclear if this is because they're in the Commonwealth or due to other factors.

Commonwealth members can leave or be kicked out

Being in the Commonwealth is not a permanent state of affairs. Members join and leave willingly, and at times have been kicked out of the organization or suspended. Most of the time, this had to do with public policy or changes in the form of government.

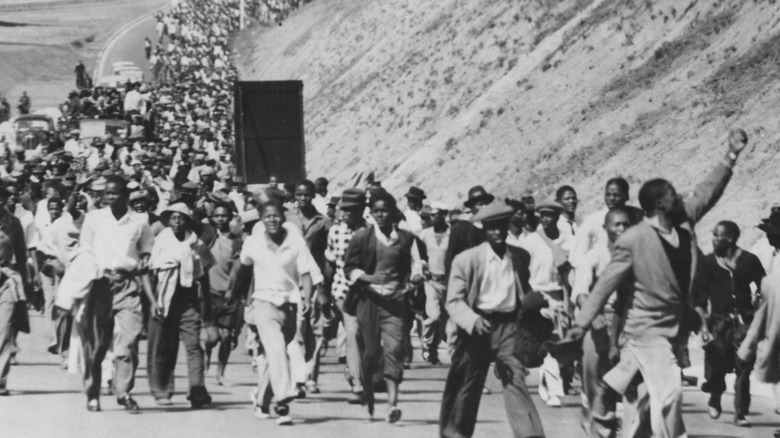

One example is South Africa, which upon deciding it was going to be a republic, withdrew from the Commonwealth in 1961. The real reason for this is explained in SAHO (South African History Online), which states that since the new republic carried on the racist policy of apartheid, the government knew that their application would be rejected. It was only in 1994 (per Britannica) and the end of apartheid that it was readmitted.

Then there is Pakistan. It first left the Commonwealth in 1972 over objections when other Commonwealth countries recognized Bangladesh as a country independent of Pakistan. It then rejoined in 1989, but 10 years later it was suspended in 1999 after a military regime took control of the country (via Reuters). Its membership has gone back and forth since.

Other countries, such as Fiji, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, have all at times been suspended due to the growth of authoritarian regimes. However, as noted by The Guardian, similar issues in Singapore, the Maldives, Swaziland, and the Solomon Islands have seemingly gone unnoticed. The fact is that the Commonwealth can do little about this since the organization has little real power except through moral condemnation.

The Commonwealth has fought for human rights ... sorta

The Commonwealth has a charter that espouses a number of principles. These include supporting democracy and human rights and promoting international peace, gender equality, and sustainable development. In other words, these are ideals to create a more peaceful, just, and fair world.

In some respects, the Commonwealth has been a strong advocate of these values. Perhaps the best example of this is the Singapore Declaration of 1971. The text of the declaration, provided by the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, advocated for an end to racial discrimination, greater equity for all, international cooperation, and a commitment to democratic principles.

Of course, there has been some criticism such as that leveled by Afua Hirsch's opinion piece in The Guardian, which pointed out how there is inequality among Commonwealth countries and that its enforcement of democratic values among its membership is patchy. Hirsch cited how the Commonwealth has suspended some countries from membership while others not, writing, "The Commonwealth is undoubtedly good at making declarations. In Singapore in 1971, it added the elimination of global disparities in wealth to the bucket list – that one is not working out so well."

The Commonwealth is not an alliance

It's sort of nebulous what benefits one gets from being in the Commonwealth. It's not a trading bloc like the European Union, and if you're a citizen of a Commonwealth country, it doesn't provide you with any particular right or benefit. And, of course, if you were a former colony of Britain, why in the world would you want to rejoin it in any form?

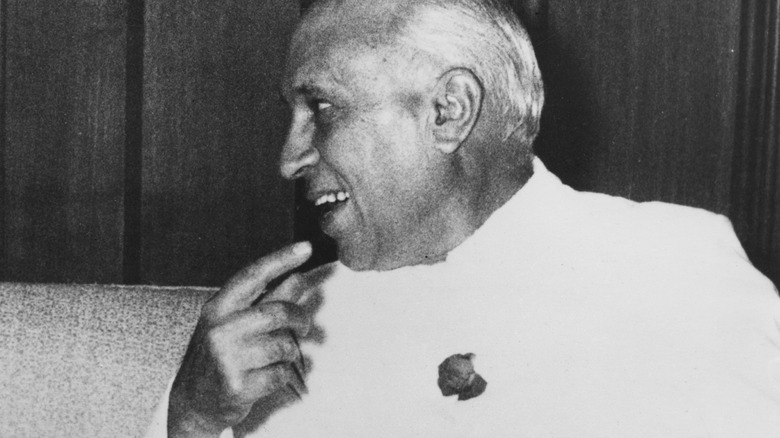

The answer to this question is explained by The Conversation, which reports that many of the leaders of newly decolonized nations were often educated in British schools and highly exposed to British culture. Both Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Muhammed Al Jinna of Pakistan went to school in the UK, for example.

Yet as colonial memories faded, countries chose to remain in the Commonwealth. To developing nations, such as those in Africa, it provides an additional forum for them to promote their interests and issues. Yet at the same time, critics have said it's mainly ineffectual and seems at times somewhat reluctant to condemn members that have moved toward more authoritarian governments despite its charter embracing democracy and human rights.

The Conversation cites that the Commonwealth did nothing in the face of questionable elections in Uganda in 2021 and also noted how in 2013, Mahinda Rajapaksa of Sri Lanka used a Commonwealth summit in hopes of cleaning up his image, which had been besmirched by accusations of war crimes.

The Commonwealth is really three organizations

The actual nuts and bolts of the Commonwealth are based on three organizations that fit together in a very loose framework. The first is the Secretariat. As reported by the UN, the Secretariat is the visionary and administrative part of the Commonwealth. This body is the one that coordinates the meetings, hosts conferences, and espouses some of the primary goals of the Commonwealth to protect democracy, advocate for human rights, promote tolerance, and bolster sustainable development while protecting the environment. The leader of the Commonwealth is the Secretary-General, who is selected by consensus from member states.

Any economic leverage from the Commonwealth comes from the Commonwealth Foundation. This body offers financial support for development and other projects through grant funding. Many grant-funded projects of late have been to mitigate or address the COVID-19 pandemic.

The third body is the Commonwealth of Learning. It's the only international organization solely devoted to education and works to promote the use of technology to encourage distance learning and the exchange of knowledge. Their efforts have brought educational technology to those who otherwise would not have access to it.

Some Commonwealth states have no connection with the British Empire

Even though the Commonwealth started with the former territories of the British Empire, some countries that never had that connection have opted to join. This started with Mozambique in 1995.

Britannica explains that Mozambique was a former Portuguese colony that had a highly fractious and disruptive history full of wars and coups. Its decision to enter the Commonwealth was somewhat puzzling since there were no direct benefits to the country. "The Historical Dictionary of Mozambique" argues the decision was because the country was geographically surrounded by other Commonwealth countries, and that in 1994 it had adopted a multiparty political system similar to other Commonwealth states.

Since Mozambique, the BBC reports that Rwanda (a former Belgian territory) joined in 2009. Rwanda's admission has not been without controversy since its president Paul Kagame has been accused of having an authoritarian regime. Kagame has been credited with helping to develop the country and notes that he upholds human rights, stating that there is "nobody in Rwanda who is in prison who should not be there."

Then in 2022, the former French colonies of Gabon and Togo joined. These two countries seemed to be mainly motivated to reduce French dependency while at the same time extending their ability to network with other countries around the world.

The Friendly Games are the Olympics of the Commonwealth

One way that the Commonwealth maintains its ties is through regularly scheduled games. Held like the Olympics every four years, the Birmingham World reports the Commonwealth Games (also called the Friendly games) brings member states together for two weeks of competition.

According to the Olympics website, the games first started in 1930 and have been held ever since, except for a hiatus during World War II. Probably the most notable happening of the games has been Roger Bannister's feat of breaking the four-minute mile at the 1954 Vancouver games. Many of the events at the games are similar to those found in the Olympics. The 2022 games website lists boxing, gymnastics, and weightlifting among the other sports. However, the games also feature less-common sports, or those more associated with the British, such as cricket, rugby, and netball.

The games have become quite an international competition. In the 2002 games, 72 nations competed, the most ever. How is this possible since there are more competing countries than Commonwealth members? The reason is that subsets of a political unit sent their own competitors. For example, the UK itself competed separately as England, Scotland, Wales, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man, among others national units.