Bizarre Things That Happened During The Great Depression

For a lot of people in the first world, "hardship" is when the internet goes out for the afternoon or when the grocery store runs out of avocados. Of course, this isn't really hardship — just look at the dismal years people suffered through during the Great Depression. Jobs were few and far between, life savings disappeared in an instant, and starvation was a very real thing. That's hardship. Still, in between all the uncertainty, the fear, and the heartbreak, some seriously weird things happened.

The ironic history of Monopoly

Nothing can tear a family apart quite like a cutthroat game of Monopoly. You may have heard the story of how it was invented by Charles Darrow in the 1930s, and how he sold it to Parker Brothers, became ridiculously rich, and lived happily ever after. That's not the whole story.

Author and researcher Mary Pilon (via The Smithsonian) did some digging into the real history of the game, and traced it back to a turn-of-the-century inventor named Lizzie Magie. She created The Landlord's Game, and it's essentially Monopoly with an extra set of rules. You could play by monopolist rules or anti-monopolist rules because she wanted to illustrate the consequences of hoarding wealth in a way people could understand. What happened next was possibly the most ironic thing that could have happened.

Sure, you could buy the official version Magie's distributor sold, but people made their own boards, too. That's what Darrow came across in 1935, copied, and sold the rights to. At the same time, Parker Brothers paid Magie $500 for the patent she'd gotten on her game, ensuring she wasn't going to get in the way of their money-maker. She didn't. Parker Brothers sold millions of copies starting in the middle of the Great Depression, and Magie died in 1948. A 1940 census recorded her livelihood as "maker of games," and her income as nonexistent.

Chain letters became ridiculously popular

Long before Facebook friends were asking you to copy and repost something as your status, there were chain letters. Mental Floss says they date back to at least the 1700s, but historian Daniel W. VanArsdale says they really became popular during the Great Depression. The premise was simple. You'd get a list of names and addresses, and you'd send a single dime to the top person. Then, you'd take their name off, add yours to the bottom, and give five people copies of the letter. The idea was that eventually the single dime you sent would turn into lots of people sending you dimes, and it's easy to see how people would want to believe.

While some lost dimes, others profited by setting up chain letter stores in a slightly more complicated scheme, Slate says. Pop-up stores would sell certificates supposedly entitling the purchaser to the benefits of having their name high up on the list — the higher on the list you were, the more people were sending you cash ... in theory. The stores were only around for a few weeks in 1935, but before the whole scheme crashed, brokers had made thousands selling certificates that were worthless. By the time people realized they weren't going to be making a fortune, as many as 3 million undelivered letters — and their well-meaning dimes — ended up in the dead letter offices of the postal service.

Dance marathons sound great but were actually heartbreaking

What would you do for a roof over your head and a few hot meals? Would you sign up to dance, and dance, and keep dancing, for days, weeks, and even months at a time? Lots of people did.

Dance marathons started in the 1920s, according to History Link, and they were endurance competitions where couples tried to be the last ones standing. Winners would receive some prize money, and they were so controversial that some cities banned them outright. (For example, Seattle stopped them after one woman attempted suicide after dancing for 19 days and only placing fifth.)

By the 1930s, it was a major industry employing around 20,000 people, including professional dancers, often ringers entered into competitions by shady promoters. Even though people knew about the ringers, they still entered marathons to dance (or, more accurately, shuffle) for 45 minutes out of every hour for weeks on end. Floor judges would keep exhausted dancers moving with a snap of a ruler, and some couples chained themselves together for support. Doctors were on hand to tend to the injured and the exhausted.

Why would people do this? Because they were fed, usually on high tables while they shuffled along in front of crowds who gathered to watch them wear themselves into exhaustion before ultimately collapsing until only one couple was left standing. "Heartbreaking" doesn't really cover it.

The debut of the world's first celebrity robot

Amazon's Alexa, iPhone's Siri, Windows' Cortana, Portal's GLaDOS ... we're still pretty impressed by artificial intelligence in the 21st century. It's actually nothing new, and the world's first celebrity robot made his debut during the Great Depression.

His name was Elektro the Moto-Man, and The Atlantic says he was built by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation for the 1939 New York World's Fair. The fair's entire theme was one of strange optimism, given the times, and Elektro was envisioned as a part of "The World of Tomorrow." He was a massive hit, performing 26 different activities including blowing up balloons, smoking a cigarette, flirting with audience members, and calling people "toots" because it was still the 1930s. He could respond to voice commands, walk, and use a vocabulary of around 700 words (with the help of his interior record player). To see that in 1939 had to be truly amazing. Westinghouse kept Elektro around through the 1950s as a demonstration of just what they could do, and he's still pretty impressive. Especially his attitude.

The Kennedy fortune

The most commonly told story of how the Kennedy family got their wealth is that patriarch Joe Kennedy had his fingers in Prohibition-era bootlegging. But author Daniel Okrent (via The Daily Beast) looked for evidence of this and found nothing. He did find that as the end of Prohibition was looming on the horizon, Kennedy started arranging deals to be the country's new importer of European booze. That's so legal it's disappointing, but there's more to the story.

Kennedy still needed some serious clout and cash to make those deals, right? According to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum's bio on Joseph Kennedy, he stepped up to take the helm of the bank his father helped found, Columbia Trust, and was well established among Boston's elite by 1917. He made a ton of financial decisions, invested in a burgeoning movie industry, and by 1929, he was a multimillionaire. He continued to be a multimillionaire while others lost everything, as he dumped all of his stocks shortly before the crash. According to the bio, he did it because of "a personal sense of foreboding and on the advice of trusted associates." The Washington Post says he did it because his shoeshine boy suddenly had stock tips to give. You decide: legit or no?

A city of 5,000 popped up along the Mississippi

It doesn't matter why you hate your apartment, it can't compare to the reasons people had to hate their living arrangements in the Hoovervilles of the Great Depression. Hoovervilles were the shanty towns that popped up across the country, named for the president who wasn't doing much of anything to help repair the damage done to the country.

When the stock market crashed, the Missouri History Museum says St. Louis was one of the biggest cities in the country. It boasted a population of 820,000, and by 1931 around 200,000 of those people were unemployed. Unemployment continued to climb, with more losing their homes as well as their jobs. That's how St. Louis became the site of one of the largest Hoovervilles, a town the St. Louis Post-Dispatch says was built from crates, canvas, and scrap sheet metal. Around 5,000 people banded together along the banks of the Mississippi, living in 600 shacks, organizing four churches, and relying on the kindness of volunteers for their survival. The so-called Welcome Inn organized the distribution of food and clothing, and matched the homeless with big-city sponsors who gave them work when and where they could. They even lived there through three floods, and it wasn't until 1936 the Works Progress Administration came in and tore down most of the shacks. So that's ... progress?

President Hoover's denial

They say ignorance is bliss, but we wish some reporter had asked President Herbert Hoover if that was the case. The Atlantic says Hoover's outright denial that anything was wrong was made even more ironic by the fact that he'd engineered the revival of a post-World War European economy, and he'd managed to get all those people fed. When it came to his own, though, he went on record as saying, "No one is actually starving." It gets weirder, as Prologue magazine says he clarified by claiming he knew of "one hobo who had managed to beg ten meals in a single day."

That's not something you say to parents wondering if they're going to be able to feed their children. At the same time Hoover refused to organize government relief programs, he kept throwing massive parties at the White House. It was to boost morale, he said, kinda like what the four-piece band thought as the Titanic was sinking.

Historian Thomas Ladenburg says the problem was a bizarre one. Hoover had grown up an orphan, working the coal mines to earn enough to put himself through Stanford. He'd been successful without any help, so that meant everyone else was going to band together, work hard, and pick themselves up by their bootstraps without any assistance, because that's how it works, right?

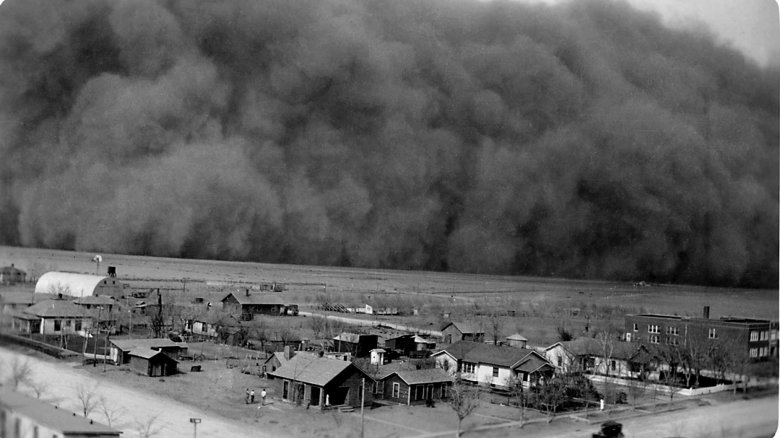

The 350-million-ton storm

Farmers have it tough, and if you've never thanked one, you probably should. It's hard work, and during the Great Depression farmers' lives went from bad to worse. At the same time the stock market was crashing, the land farmers had been plowing for decades was turning on them. Topsoil and prairie grass was gone, and the dust storms came.

It's hard to imagine the scale we're talking here. On May 10 and 11, 1934, a single storm picked up 350 million tons of dust, dirt, and silt from the Midwest and dumped it across the East Coast. According to The New York Times (via History), ships floating hundreds of miles off the coast were covered in a fine layer of dirt from the Midwest. The Washington Post tries to put the insanity in perspective like this: That's 3 tons of dirt for every person living in America at the time. The storm was 1,800 miles wide, and 6,000 tons got dumped on Chicago alone. Even New York City stopped, as people were unable to travel or do business in the darkness of midday.

That's not the only storm that ravaged the country during the Great Depression, either. Black Sunday plunged the Midwest into complete darkness on an April afternoon in 1935, and another storm brought 40 mph winds for 100 straight hours, proving things can always get worse.

Miniature golf was huge

Life was pretty terrible, but people still needed a way to pass the time. Entertainment was a luxury, but miniature golf was a luxury many people could afford, especially when they made the courses themselves. The Jacksonville Historical Society says it was so popular it was called "The Madness of 1930," and movie studios were so afraid courses were going to take people away from the theater they tried to keep their biggest actors from playing. They couldn't.

Mental Floss says miniature golf courses were originally called "rinkie-dink" courses, and their popularity came because they were easy to set up. Obstacles could be made from whatever was lying around, which is a big bonus when you have next to nothing to work with. Informal courses used garbage cans and gutters, while commercial courses started advertising bigger and better gimmicks, from trick shots and traps to (in one case) a trained monkey who had been taught to steal golf balls. Knowing how competitive people can get, this may have been unsafe for the monkey. Hopefully he was trained to dodge, too.

Car manufacturers invented obsolescence

You know the drill. You save up for something awesome, only to buy it right before the next generation of it is announced a month later. You can thank General Motors and the Great Depression because according to Timeline, they're the ones who invented planned obsolescence.

Originally, people would buy a car when the old one broke. Ford had made them all pretty much the same, after all, and there's no reason to buy a new one to keep up with the Joneses when all the Joneses are driving the exact same Model T. But when GM needed to find a way to survive the Depression. How to keep people buying cars? By making new, must-have models, different products, and a desire that was way more powerful than a mere want. It had to be a need.

In all fairness, GM wasn't the only company that did it. In 1932, one real estate agent even suggested doing the same with things like clothing and furniture, assigning them "best-by" dates and putting it into consumers' heads they needed to buy the newest models. That specific idea didn't catch on, but the world never looked back.

The U.S. Mint stopped minting

How bad was it really? When the background processes you never really think about just stop, it helps put things in perspective. That's what happened with the U.S. Mint for years at the height of the Great Depression.

CoinWeek says there's a sure-fire way to know that 1931 half dollar you're thinking about investing in is a fake: There's no such thing. As the Depression ground on, more and more coins were stuck piling up in the vaults of the U.S. Mint. There were so many coins in storage that the Mint just stopped producing more. There were no Buffalo nickels or Mercury dimes minted in 1932 and 1933, no half dollars made between 1930 and 1932, and no silver dollars made between 1929 and 1933. The coins that were minted during these times were produced in much smaller quantities than usual, even Lincoln pennies. Where they'd minted around 277 million pennies in 1929, only a little over 24 million were made in 1931. You might say that the Great Depression nickel-and-dimed everyone, even the U.S. Mint.