The Bizarre So-Called Curse Of Abraham Lincoln's Only Heir

As historian Todd Arrington explains (via National Park Service), Robert Todd Lincoln was the eldest and longest-surviving son of President Abraham Lincoln and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. His younger brother, Edward, died as a young child in Illinois long before his father was elected president. Another brother, William, died during Lincoln's presidency, in 1862. Robert's youngest brother, Thomas, known as Tad, died in 1871, a mere 18 years old. In contrast, Robert, the oldest son, lived to be nearly 83 years old. Nevertheless, Robert himself might not have taken his long life as a blessing.

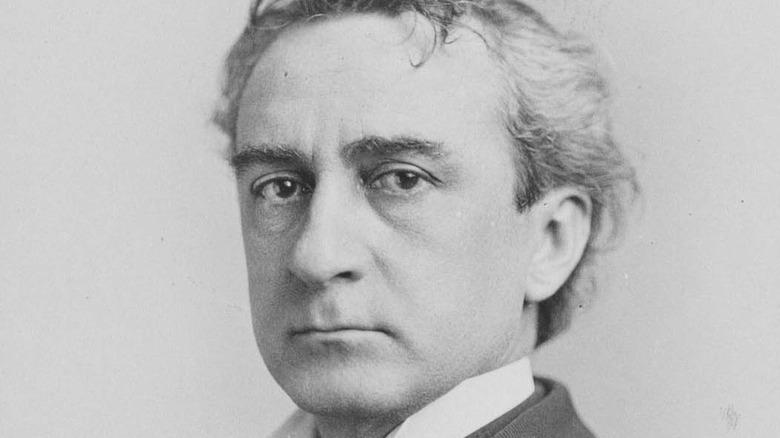

The History Reader says that Robert Todd Lincoln did not resemble his more famous father in either looks or demeanor. He was seven inches shorter and stockier in build, and he was apparently boring and unpleasant to talk to, lacking his father's charisma and charm. Despite this, during his lifetime, Robert served as the U.S. Secretary of War and Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of St. James, as well as working as a successful lawyer and president of the Pullman Palace Car Company, a position which made him a millionaire who lived in a 24-room mansion. He was even asked to run for U.S. president multiple times, but he refused. In spite of this apparent good fortune, however, Robert Todd Lincoln is said to have thought himself cursed and allegedly said once when invited to the White House, "There is a certain fatality about presidential functions when I am present." What, you would be right to ask, is that all about?

A Booth saves a Lincoln

Before the string of coincidences that led Robert Todd Lincoln (and others) to believe his presence was detrimental to the health of American presidents, he was involved in a bizarre incident that serves as a great example of the bittersweet mix of good luck and tragic coincidence that plagued Robert throughout his life. As HistoryNet records, Robert was traveling by train from New York to Washington, D.C., on a break from his studies at Harvard some time during the Civil War — probably 1863 or 1864. While switching trains in Jersey City, New Jersey, Robert found himself on a crowded train platform, crammed back so that his body was pushed against the stationary train. Suddenly, however, the train started moving, which knocked Robert off his feet and caused him to fall into the gap between the platform and the train.

Before the president's son could be crushed by the train's wheels, making a clean sweep of dead Lincoln boys, Robert found himself grabbed by the collar and hoisted up to safety. When he looked up to see who had saved his life, he instantly recognized him. And why wouldn't he? It was only the most famous Shakespearean actor in America, Edwin Booth (above). If the last name seems familiar, it's because Edwin was the brother of John Wilkes Booth, the less successful actor who would go on to assassinate Robert's father, Abraham Lincoln, in Ford's Theatre in 1865. (It is perhaps of note that Edwin was estranged from his brother precisely because Edwin was pro-Lincoln, but he didn't even know until years later that he had saved the president's son.)

The curse begins

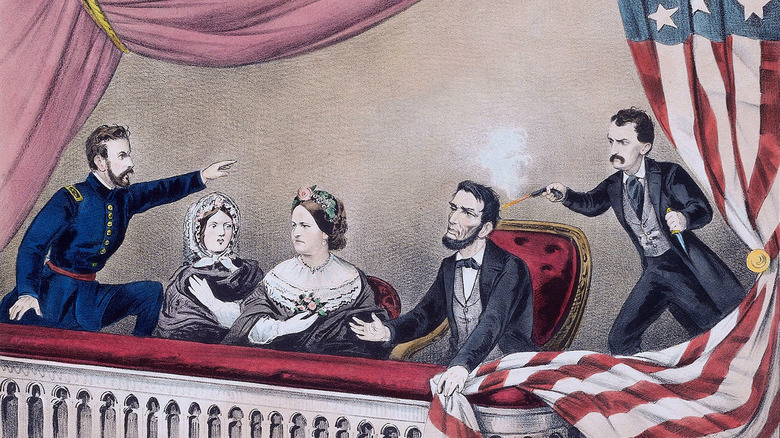

Within a year or so of Robert's close call on the train platform, his first encounter with presidential death hit, and hit as close to home as possible. As Todd Arrington recounts, in April 1865, Robert Todd Lincoln was serving as a captain in the Union Army as staff under General Ulysses S. Grant and was at the White House with his father and mother. His parents invited Robert to come with them to see a play at Ford's Theatre, but he said no, as he was intending to go to bed early that night. That was the night that resulted in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln during a performance of "Our American Cousin."

A number of different people ran to tell Robert that his father had been shot and taken to the Petersen House across the street from the theater. Robert hurried there and found his father still alive but unconscious. According to the elder Lincoln's private secretary (and future Secretary of State) John Hay, Robert spent the rest of the night weeping at his father's bedside and comforting his grieving mother. Robert was still there at Lincoln's bedside when the president succumbed to his gunshot wound and died on April 16, 1865. Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be assassinated, but not the last, and to Robert's great distress, not the last presidential assassination that he would be present for in the next couple of decades.

Witness to an assassin's bullets

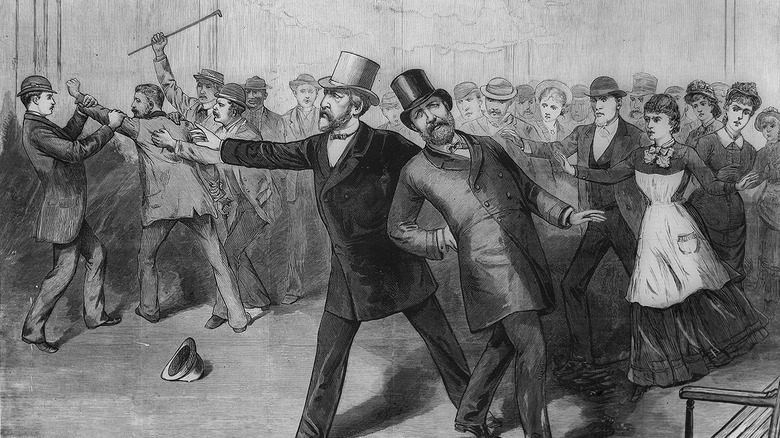

As Todd Arrington explains, the Republican Party spent the next 15 years after Abraham Lincoln's death trying to recruit Robert Todd Lincoln to run for office. Robert declined, probably rightly assuming that they were largely banking on the prestige of his last name more than an interest they had in him personally. Eventually, however, he did give in and agreed to serve as Secretary of War under Republican president James Garfield starting in 1881 (per Biography). This, unfortunately, set Robert up for his next encounter with presidential death.

On July 2, 1881, President Garfield was traveling to New England, but Robert wasn't able to depart until the next day, so Robert went to meet the president at the train station to tell him that he would see him there a day later. While he was walking toward the president and about 40 feet away, assassin Charles Guiteau came up to Garfield and shot the president twice. Robert immediately flashed back to the murder of his father and later said to The New York Times, "How many hours of sorrow I have passed in this town." Garfield held on for another 80 days but died on September 19, after which Vice President Chester A. Arthur ascended to the presidency. Arthur ended up replacing every member of Garfield's cabinet with men of his own choosing, except for one: Robert Todd Lincoln, who continued to serve as Secretary of War until the end of Arthur's term as president, after which Robert returned to private legal practice.

Death at the World's Fair

As Todd Arrington continues, over the next 20 years, Robert Todd Lincoln worked as an attorney before being appointed the U.S. Minister to the Court of Saint James in the United Kingdom during President Benjamin Harrison's administration, after which he became first the general counsel and ultimately president of the Pullman Palace Car Company, which made him tremendously wealthy. It was in 1901, 20 years after he had witnessed the assassination of James Garfield, that Robert took his family to Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, on the way back to their home in Chicago from a family vacation in New Jersey. The Expo was a world's fair designed to promote and celebrate cultural and economic exchange between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

Just as the Lincolns' train pulled into the station in Buffalo, Robert was handed a telegram informing him that President William McKinley had just been shot twice in the abdomen by the anarchist Leon Czolgosz. Robert immediately left the station to go to the home of the Expo president, where McKinley had been taken to rest after surgery. After a visit with the president — and a subsequent one two days later — Robert was convinced that McKinley would be fine, as his health seemed to be improving. The Lincolns then returned home, and McKinley died of infection a week later. When Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in as president, Robert sent him a letter saying, "I do not congratulate you, for I have seen too much of the seamy side of the Presidential Robe to think of it as an enviable garment."

Was Robert Todd Lincoln really cursed?

As The History Reader points out, Robert Todd Lincoln experienced other great tragedies, besides a connection to the first three presidential assassinations. In addition to the deaths of his three younger brothers, Robert's only son, Abraham Lincoln II, died at age 16 from a blood infection. Likewise, his mother, who had already become infamous for her strange behavior, became increasingly erratic until Robert had to have her committed to a mental hospital, ruining his relationship with her for the rest of her life. Todd Arrington also notes that Robert's last public appearance was at the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922, where President Warren G. Harding oversaw the dedication before dying 14 months later. No one seems to add this to Robert's presidential death total, however, presumably because it wasn't an assassination and because so much time passed in between their meeting and Harding's death.

Arrington points out that while it's tempting to see Robert as "cursed," you have to remember that Robert was a politically prominent person during a time of great political strife, whose association with the presidency made him much more likely to be around presidents than a normal person. Also, he wasn't actually present at the assassinations of either his father or McKinley, just kind of in the same city. Cursed or no, Robert Todd Lincoln certainly lived a life surrounded by death that would be difficult for anyone. His own death came in 1926 just before he turned 83, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.