The Unexpected Origins Of Firewalking

Would you walk across hot coals to honor a promise or prove your inner strength? This is called firewalking. And while it sounds too uncomfortable to have a name, it has emerged in cultures around the world. According to Expedition, it is still practiced today in many places, including India, Greece, Spain, China, Japan, Bulgaria, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Fiji, and Tibet.

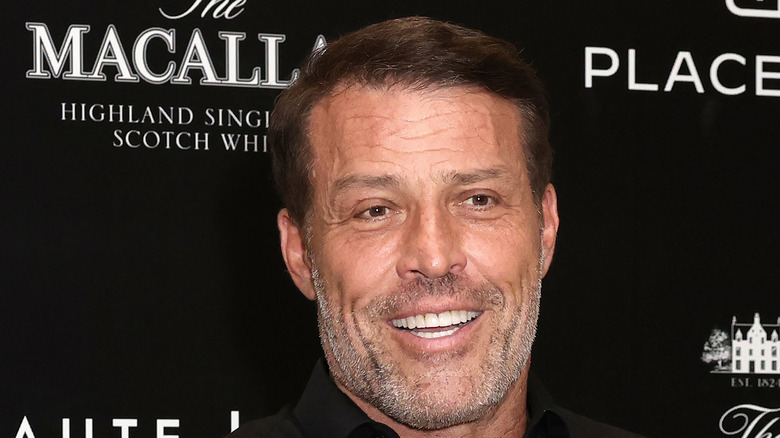

Firewalking is typically done for spiritual purposes like honoring a saint, fulfilling a vow, or celebrating the anniversary of a miracle. It is also undertaken to ensure a good harvest or to prove the innocence of someone accused of a crime, according to Britannica. Practitioners believe that only the guilty or faithless will be harmed by the practice, but scientists like David Willey have recently explained that people can walk on hot coals unscathed because of physics. It has also transitioned into the secular world through the firewalk events held by motivational speaker Tony Robbins (per the Los Angeles Times). Leading others in the practice is something you can now learn at institutions like the Firewalking Center.

First sparks

Because it is such a widespread practice with ancient origins, it isn't clear exactly when and where firewalking first emerged. Some practitioners believe it started in Central Asia, according to Expedition. In "Holiness Ritual Fire Handling: Ethnographic and Psychophysiological Considerations," Steven M. Kane attributes the first mention to an Indian legend from around 1200 B.C. when two priests were arguing about which was the "better Brahman," according to Kane. To settle their dispute, they both walked through fire. "One of the contestants, it is reported, vindicated his claim to superior holiness by emerging from the ordeal without so much as a singed hair," Kane wrote.

There are also written descriptions of a related practice in the works of ancient Roman writers Pliny the Elder, Strabo, and Virgil, among others, according to Penn Museum. In the version recorded by Pliny the Elder, who lived between 23 and 79 A.D., a family by the name of Hirpi worked out a pretty sweet deal. Expedition reports that Pliny the Elder wrote, "[A]t the yearly sacrifice to Apollo, performed on Mount Soracte, walk over a charred pile of logs without being scorched and who consequently, under a perpetual decree of the Senate, enjoy exemption from military service and all other burdens." During the Middle Ages, there were also reports of firewalking. According to Kane, a Florentine monk earned the name St. Peter Igneus when he was canonized for walking over hot coals in 1062 without getting burned.

Little fires everywhere

Since the first accounts, various firewalking traditions have sparked and burned steadily around the world. According to Expedition, generally, firewalking practices take one of two forms. The first is walking over stones that were previously heated. This is how it is practiced in Fiji and Mauritius, according to Britannica. On the Fijian island of Beqa, the tradition is said to have originated with a fisherman named Tuinaiviqalita, who was granted the ability to firewalk in exchange for sparing the life of a spirit creature he caught when fishing for eel, according to The Fiji Times.

However, according to Expedition, the more frequently-practiced variation has firewalkers traversing over hot coals. The coals are typically heated with wood until the fire is white with blue flames that extend at a maximum of 2 inches in the air. This form of firewalking is practiced from San Pedro Manrique in Spain to celebrate St. John's Eve to certain villages in Thailand, where the practice honors local saints, to the Kataragama religious festival in Sri Lanka, according to Expedition and Kataragama Devotees Trust. In Spain, participants move across a 3-by-7-foot bed of embers; in Sri Lanka, a 10-by-15-foot bed; and in Thailand, a heaped pile, according to Expedition.

The Anastenaria ritual

One example of a firewalking practice that has survived from the ancient era is the Anastenaria ritual in northern Greece. According to The New York Times, the name Anastenaria comes from the Greek word, anastasi, which means resurrection. It is performed as part of a three-day festival in the town of Lagadas to honor the Greek Orthodox saints Constantine and Helen. However, some experts believe it emerged from the ancient Greek worship of Dionysus. There is also a local legend dating from 1250 A.D. that connects the practice to the Orthodox church, according to Expedition. A fire started in the church of St. Constantine in Kosti, and villagers heard groans coming from inside the burning building. They believed that the icons were moaning for help, so a brave few raced into the church to save them. They emerged with the icons entirely un-singed, a sign of holy gratitude. The descendants of those first rescuers then promised to commemorate the miracle by walking through fire once a year.

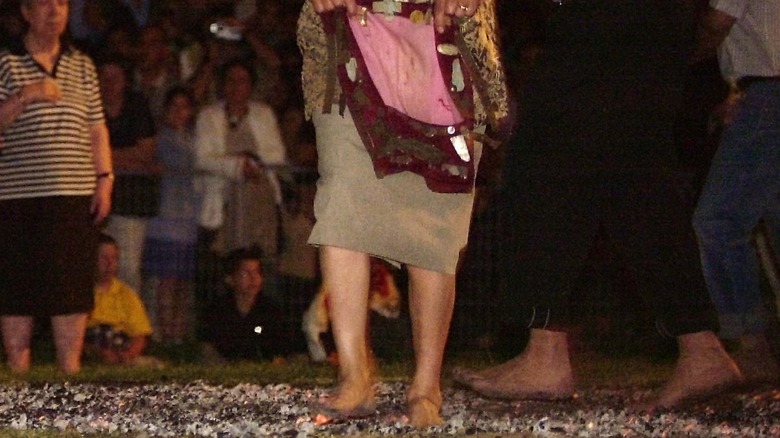

Today, firewalking is accompanied by music and dancing, according to The New York Times. The icons are placed in a shrine called a konaki besides sacred red cloths called amanetia. Demetrios Ioannou had a chance to observe the ritual in 2016. "The celebrants removed the carpet, scattered the burning coal on the ground and, one by one, started walking on it, barefoot, with closed eyes, almost drunk with the emotions of the moment," he wrote for The New York Times.

The science of firewalking

While firewalking is a part of many religious practices and has an element of mystery and mysticism to its success, scientists in the twentieth century were able to figure out why it works, according to David Willey. In 1935 and 1937, the University of London Council for Psychical Research organized two firewalks to try and understand how the practice worked. While some participants received minor burns, three emerged entirely unscathed. Based on these results, the council determined that firewalking was possible because burning wood does not conduct heat very effectively and because the walkers' feet didn't stay in contact with any single coal for long. Wiley, who has conducted his own firewalks, also thinks that the ash from the burning embers can act as a light barrier.

A paper published in the Skeptical Inquirer in 1985 by Bernard J. Leikand and William J. McCarthy came to a similar conclusion but added another possibility. Some firewalkers may benefit from something called the Leidenfrost effect. This is what happens when a liquid comes in contact with a hot surface, according to Science Notes. The first layer of liquid to touch the heat will vaporize, protecting the rest of the liquid from boiling immediately. This same protective layer could cushion the feet of firewalkers if their feet are sweaty or damp, Leikand explained. However, a protective liquid-vapor layer isn't necessary for firewalking to work because firewalkers in Sri Lanka actually dry off their feet before stepping on the coals.

Firewalk with me

During the 20th and 21st centuries, a new tradition of firewalking emerged. During the early 1980s, self-help and self-motivation courses began to use firewalking as part of its program, David Willey explained. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the firewalks conducted by life coach Tony Robbins as part of his Unleash the Power Within event. For Robbins, firewalking serves as a metaphor for finding the strength to fix persistent problems in one's life. "We are trained, almost innately, to be scared of fire and to keep away from it. That is why walking through a pathway of fire is a powerful expression of moving beyond one's fears," he told HuffPost.

There have been some accounts of people being injured at Robbins' firewalking events. After a session in San Jose, California, in 2012, The Mercury News reported that at least 21 people were treated for burn injuries. "I heard wails of pain, screams of agony," passerby Jonathan Correll told the paper. However, HuffPost reported that the media accounts were overblown. People at the events often yell and scream to psych themselves up for the walk but not necessarily out of pain. Robbins said that usually 1% of people will experience hot spots or blistering and at the San Jose event that only a third of that 1%, or 21 out of 6,000, had this happen. Additionally, there are also medical professionals on-site during Robbins' walks.