American Political Feuds That Got Out Of Hand

Politics can be vicious. Watching a presidential primary debate between candidates who are theoretically on the same side can seem like a lesson in passive-aggression and taking someone down a peg or two. But viewers don't expect actual violence to break out. Even the most contentious political debates aren't supposed to end with one politician picking up their podium and throwing it at their opponent.

Nevertheless, American politics has descended into this kind of violence in the past, and worse. Some politicians were injured or even killed over political and personal differences that seemingly couldn't be solved with mere words. Not all of this occurred on a national stage — sometimes, it is statehouses that see local politics go beyond the bounds of propriety.

While politics in modern times can seem more aggressive than ever, just be thankful it hasn't resulted in any situations like these ... at least not yet. Here are some American political feuds that got out of hand.

Aaron Burr vs. Alexander Hamilton

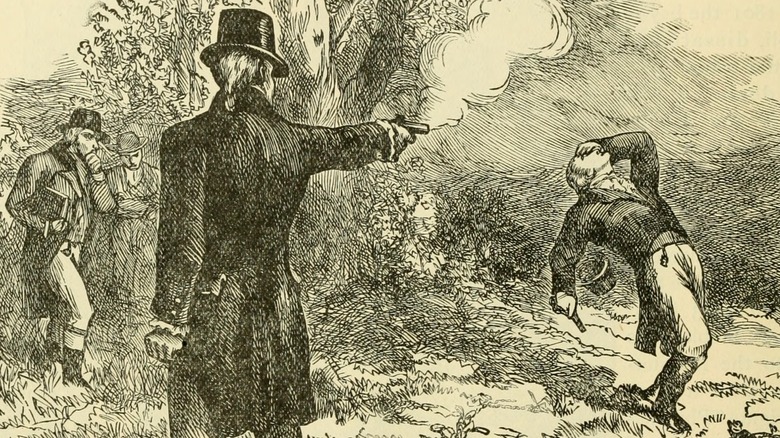

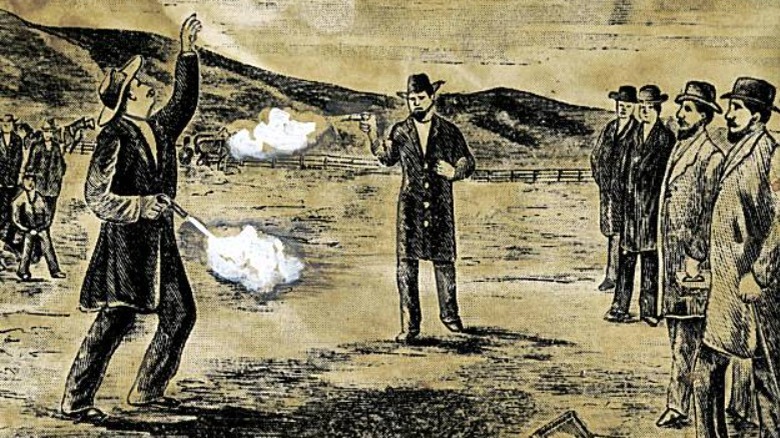

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr were political rivals for over a decade, thanks to complicated political wheeling and dealing (per Britannica). Per PBS, in the election of 1800, Hamilton even played a key role in keeping Burr from winning the presidency. A powder keg of enmity between the two was primed and ready to ignite when Burr lost the 1804 New York Governor's election, again partly thanks to the influence of Hamilton. Later that year, at a dinner party, Hamilton expressed a number of very uncomplimentary opinions about Burr, who found out after they were published in the New York newspaper, Albany Register.

It seemed that the only thing that would restore Burr's honor and his political career after all these insults was a duel, so Hamilton was challenged. Hamilton was left with little options but to accept the duel, even though his eldest son Philip had been killed in one some years prior. In the early morning of July 11, 1804, Hamilton and Burr came together in secret at Weehawken, New Jersey, along with their "seconds." Both men had served with distinction in the Revolutionary War, but Hamilton had left his shooting skills to fall fallow and also expressed his intent to purposefully miss. Burr, on the other hand, had been practicing his marksmanship prior to the duel, and it showed, with his shot hitting Hamilton square in the chest, resulting in his death some 31 hours later.

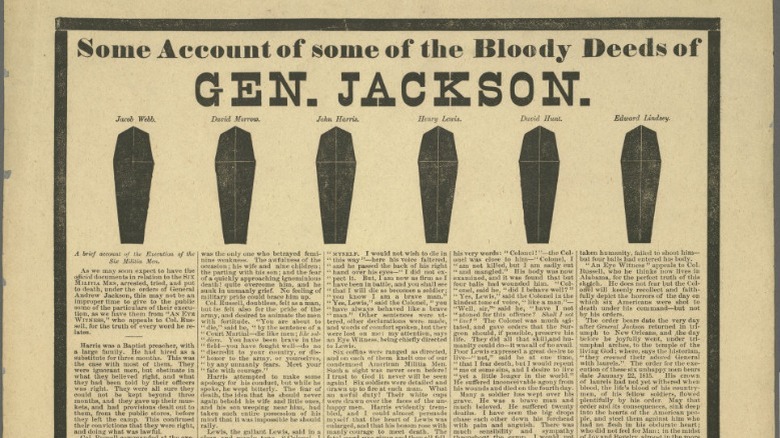

John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson had reason to be angry when he faced John Quincey Adams in the race for the White House in 1828. They had run against each other four years before, and Jackson had effectively been cheated out of the win by backroom dealing, according to the White House Historical Association. So in 1828, neither pulled any punches, but Adams' campaign was particularly vicious, including spreading insulting rumors about Jackson's wife, Rachel, in the press. When Rachel died shortly before Jackson was inaugurated, he blamed these stories for contributing to her death.

The culmination of this vicious campaign was Andrew Jackson's election to the presidency and a rabid mob of his supporters descending on the White House after his inauguration. The Atlantic says it was so bad that John Quincy Adams had to escape out a back exit to avoid the overexcited crowd, although other records say he left earlier that morning to avoid such a life-threatening situation. It would have been dangerous to meet the mob of Jackson supporters, who stormed the White House by the thousands. The Washington socialite Margaret Smith was an eyewitness and wrote to a friend about the chaos: "Ladies fainted, men were seen with bloody noses, and such a scene of confusion took place as is impossible to describe."

Charles Sumner vs. Preston Brooks

The lead-up to the Civil War was dangerous for anyone who was outspoken in their beliefs over the enslavement of Black people. Disagreements were so fraught that the book "Field of Blood" is dedicated just to the violence that took place in the U.S. Congress in the years before the country officially split in two. The most infamous act of the kind went down in history as "The Caning of Senator Charles Sumner."

The decision of whether Kansas should be a free state or a state of enslavement was so fraught that it ended in the events of "Bloody Kansas." According to the United States Senate's official website, a debate over Kansas' entry to the Union also ended in blood in the Senate in 1856. In his speech on the subject, abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner had some harsh words for one of his opponents, Andrew Butler, who was absent. Sumner said Butler kept "a mistress ... who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight — I mean the harlot, Slavery."

Butler's friend, Rep. Preston Brooks, was incensed on Butler's behalf. Instead of challenging Sumner to a duel — which would have been controversial but at least considered appropriate at the time — three days later, Brooks attacked Sumner out of nowhere, beating him with a cane on the floor of the Senate. Badly injured, Sumner would recover, but the attack further divided the nation.

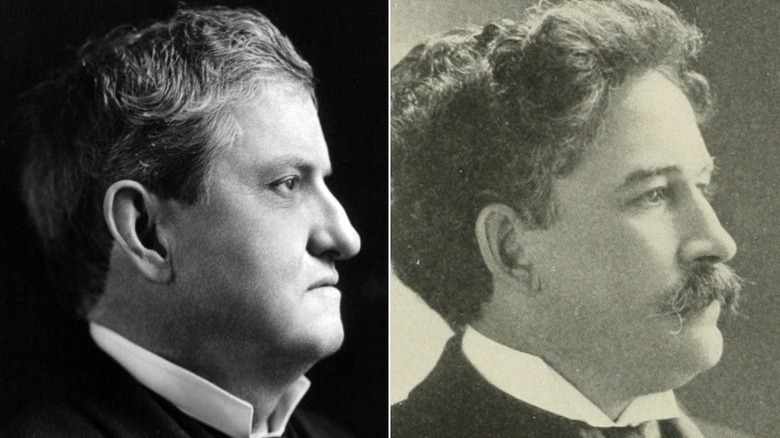

Benjamin Tillman vs. John McLaurin

John McLaurin joined the U.S. Senate in 1896 after a long mentorship by his old friend Benjamin R. Tillman, an outspoken man who had also served as South Carolina's governor before his election to the Senate (via the Senate Historical Office). Their relationship turned sour, though, after McLaurin, wooed by the Republicans, began to turn away from his former patron.

During a Senate debate over a treaty to annex the Philippines in February of 1902, Tillman launched into a furious verbal tirade toward McLaurin's empty seat, the latter then being elsewhere in a committee meeting. Charges of treachery under "improper influences" and Republican rewards of political favors for McLaurin flew from Tillman to the vacant chair, but not for long. Tillman's accusations soon caught the ears of McLaurin, who abandoned his meeting to rush back to the Senate Chamber and confront the former South Carolina governor.

McLaurin had harsh words for Tillman, accusing him of "a willful, malicious and deliberate lie," after which Tillman flew toward McLaurin with his fists flying (per the Senate Historical Office). Tillman's windmilling punches managed to not only land on McLaurin but also on several other members trying to separate the two. Once separated and after a closed session, the two did apologize, but with such contempt that another fight nearly ensued. For their actions, both senators were eventually censured, and Tillman suffered another indignity — a snubbing by President Franklin D. Roosevelt (via The New York Times).

Robert S. Robertson vs. the Indiana General Assembly

In 1886, Indiana voted for their next lieutenant governor and successor to Governor Isaac P. Gray, who was tapping his feet waiting to fill a recently vacated U.S. Senate seat, as described by the Indiana Historical Bureau of the Indiana State Library. The expectation was that another Democrat, Senate President Alonzo G. Smith, would win, but the Indiana General Assembly was thrown into turmoil when a Republican, Robert S. Robertson, won instead. Faced with the prospect of a Republican successor to a Democrat governor, the Indiana General Assembly bitterly resisted Robertson's attempts to assume his elected office as lieutenant governor and president of the senate. Court appeals eventually found the Indiana Supreme court, which ruled in Robertson's favor on February 23, 1887. Bolstered by this, Robertson strode into the Senate chamber the next day and demanded his seat, pushing through the agitated crowd towards the protesting Smith.

Amongst this furor, a doorkeeper suddenly grabbed Robertson by the throat and "threw him some 15 or 20 feet from the steps," as reported by the Indianapolis Journal. Smith demanded Robertson's removal from the chamber, exclaiming, "If this man persists, remove him from the floor." Forcibly removed outside, Robertson made a further speech, inflaming more fighting beyond the chambers. The event extinguished Governor Gray's ambitions for the U.S. Senate and even gave more momentum to the eventual 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, with the direct election of U.S. senators.

Roger Pryor vs. John 'Bowie Knife' Potter

In 1860, one year before the U.S. civil war, Roger Pryor and Owen Lovejoy engaged in a heated argument over slavery in Congress, as told by Wisconsin Life. The abolitionist Lovejoy was in the middle of an animated condemnation of slavery when Virginia Congressman Pryor jumped up and shook a fist in his face to the approving jeers of Pryor's fellow pro-slavery members. Rising to Lovejoy's defense was a furious Wisconsin member named John Fox Potter, his broad black mustache trembling with outrage.

This hirsute gentleman from Wisconsin would go on to make an unforgettable name for himself after Pryor accused Potter of interfering with the records of the debate (Pryor also claimed that language was falsely added) and challenged him to a duel. Potter accepted the duel but upped the ante by stating terms for combat that were as overtly masculine as his lip foliage. As reported in The New York Times, Potter agreed as long as the duel was fought with bowie knives, commencing from four feet away.

Denouncing this as barbarous, Pryor backed down, earning Potter considerable respect from his peers, as well as the nickname "Bowie Knife Potter." Bowie knives were sent to him from around the country, and he was once personally presented with a giant seven-foot bowie knife, inscribed with "to John Fox Potter who will always meet a Pryor engagement," further heaping scorn on Pryor.

Roger Griswold vs. Matthew Lyon

In 1798, U.S. Representatives Roger Griswold and Matthew Lyon had an ongoing disagreement over the new nation's diplomatic stance toward France, per the Office of the Historian at the U.S. House of Representatives. Lyon opposed war preparations, while Griswold supported then-president John Adams with a more hawkish approach in the face of hostilities. The two politicians — Griswald, a Federalist from Connecticut, and Lyon representing Vermont as a Republican — had little love between them following a prior incident, when Lyon had spat tobacco juice in Griswald's eye after being accused of being a coward.

The House of Representatives took a vote on January 30 over whether to expel Lyon for the spitting offense when tensions again boiled over between him and Griswald, as described by ConnecticutHistory.org. Griswald's Federalists were unable to gather a two-thirds majority in the vote to secure Lyon's expulsion, so instead, Griswald took it upon himself to decide the matter with his hickory walking stick. On February 15, the day after the vote, Griswald went up to Lyon on the house floor and commenced beating him with the stick. Lyon defended himself by grabbing a nearby pair of fire tongs and fighting back. Fists flew, and eventually, members of Congress had to pull the two fighting politicians apart, all of which was merrily illustrated in satirical press cartoons.

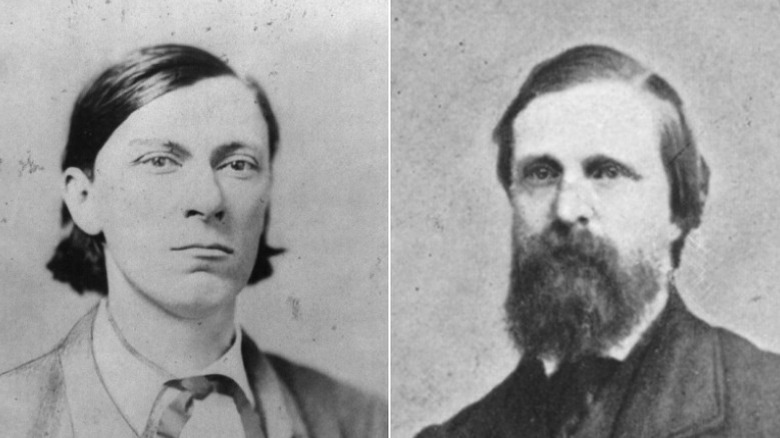

David Broderick vs. David Terry

The disagreement over enslaving Black people saw many political friendships destroyed in the mid-1800s. One of those was that of California Democrats David Broderick and David Terry. Despite belonging to the same party, the National Parks Service says the two stood on opposite sides over the slavery debate in California in the 1850s.

David S. Terry was a chief justice of the California State Supreme Court who had already shown an inclination to violence and was staunchly pro-slavery. United State Senator David C. Broderick believed California should be "Free Soil." With no middle ground on such a major issue, their friendship fell apart. Then, Terry failed to win reelection to his spot on the court. According to the ACLU of Northern California, blaming Broderick for his failed reelection bid, Terry insulted his former friend in a speech. When Broderick returned the insults, Terry challenged him to a duel. Despite duels being illegal, not only did Broderick accept, but so many people showed up to gawk on the day the event was planned that it had to be rescheduled. When they finally met on the field of honor without the mob of spectators, Broderick was at a real disadvantage. He'd never fired the kind of pistol the pair were using while Terry had been practicing extensively. Terry shot and killed Broderick, who was later hailed as an abolitionist hero.

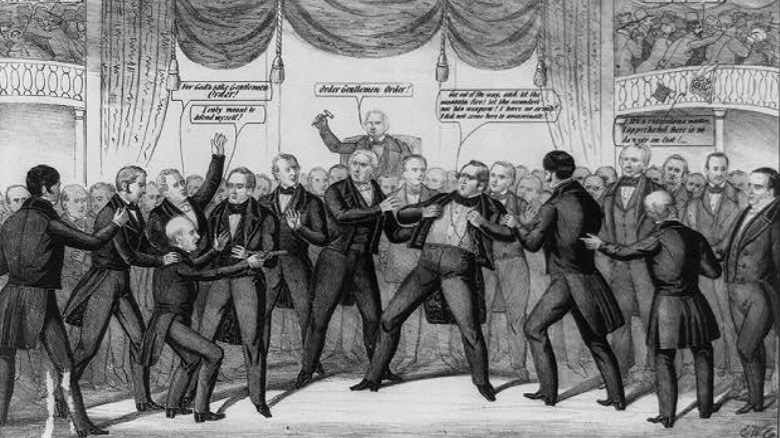

The mass brawl in the U.S. House of Representatives

The introduction of Kansas to the United States as a state was seemingly impossible to even discuss without violence. Just two years after a debate over the proposed state ended in the caning of Charles Sumner, an even bigger fight broke out in the U.S. Congress. As the United States House of Representatives History, Art, and Archives explains, the debate over whether or not to ratify the proposed "Lecompton Constitution" for the state of Kansas was contentious, and the debate raged well into the night.

Perhaps worse for wear, around 2 a.m., Pennsylvania Republican Galusha Grow and South Carolina Democrat Laurence Keitt began yelling insults at each other. Suddenly, fists were flying. And not just from the two men — over 30 other members of the House finally snapped and started to take their anger out on their opponents the way they had probably been wanting to for a long while. Even the threat of arrest wasn't enough to calm the brawlers. But then, there was an unexpected moment of respite when Rep. John "Bowie Knife" Potter and Rep. Cadwallader Washburn snatched Rep. William Barksdale's toupee off his head. Even in the midst of their fistfight, the members had to stop and laugh at this sight, allowing the sergeant-at-arms to regain control of the chamber.

William Graves vs. Jonathan Cilley

The 1800s were a complicated time both politically and when it came to how men felt about their honor and perceived insults to said honor. The death of U.S. Rep. Jonathan Cilley did not need to happen except for extraordinary circumstances brought on by these issues.

According to "Ancient American Politics," the Democrats and the Whigs were increasingly at odds with each other in the 1830s. The Democrats believed one newspaper, in particular, was too pro-Whig. The United States House of Representatives History, Art, and Archives records that Rep. Cilley accused the editor of the newspaper, John Webb, of taking bribes in a speech on the floor of the House. Webb was furious and decided to challenge Cilley to a duel. However, he asked his friend Rep. William Graves to deliver the challenge in the form of a letter.

When Graves tried to hand Cilley the letter, the latter refused to take it from him. For reasons that no longer make sense, Graves decided this refusal was so insulting that he needed to challenge Cilley to a duel as well. Despite the fact that the only issue between the men was this undelivered mail situation, Cilley accepted. The day of the duel, both men missed their first two shots, but they decided to keep going. On the third shot, Cilley was hit and bled to death.

Henry Foote vs. Thomas Hart Benton

It may not surprise you by now that politicians in the decade before the Civil War were quick to anger over the subject of slavery. One can see why this subject brought more passion from those who were pro- and against the "peculiar institution," more so than, say, deficit spending. But perhaps it is shocking just how often these arguments led to violence.

It was at a funeral, of all places, that the U.S. Senate's official website says tempers flared so badly that then-Vice President Millard Fillmore had to warn the members to calm down right then and thereafter. He made clear he knew things in the chamber were heading toward violence, saying, "A slight attack, or even insinuation, of a personal character, often provokes a more severe retort, which brings out a more disorderly reply, each Senator feeling a justification in the previous aggression." Per the U.S. Senate's official website, Mississippi senator Henry Foote and Missouri senator Thomas Hart Benton were two of the members exchanging heated insults. Two weeks after this warning, on April 17, 1850, the rivals came precariously close to a deadly encounter in the U.S. Senate. After an angry back-and-forth, Benton made a menacing advance toward Foote. Foote, knowing he was in danger, pulled a pistol in response. Fortunately, Foote agreed to put down the gun before the situation got any worse, after which the two men were physically separated.

Joseph Anthony vs. John Wilson

According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, it seems everyone who witnessed the only deadly episode on the floor of the state's general assembly had a slightly different version of what happened. What is known is that the members were debating a bill on wolf scalping. The bill would have allowed citizens to be paid by the state for every wolf they killed, with the scalps being proof of the deed. Rep. Major Joseph J. Anthony made a comment about the bill that Speaker of the House Colonel John Wilson took personal offense to, and after some back and forth insults, Wilson pulled a knife and stabbed Anthony to death. A local paper called the killing "another example of the barbarity of life in Arkansas," one which had no less than "stained the history of the state."

Wilson's defense against the charges was that he was simply defending his honor. This worked, as the jury decided he was "guilty of excusable homicide," which was them saying that they knew Wilson was responsible for the death of Anthony, but they understood why he did it, so it was acceptable. Wilson was even reelected after his trial, this time to the Arkansas House of Representatives. There, once again, he got so mad he tried to attack a political opponent, although this time he didn't kill him, which was an improvement.

Sen. Markwayne Mullin vs. teamster head Sean O'Brien

Sen. Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma and Teamsters Union head Sean O'Brien are no strangers to butting heads, although they've usually reserved that for social media. On November 14, 2023, the two nearly came to blows during O'Brien's testimony before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. During questioning, Mullin read one of O'Brien's old tweets from June 2023, where O'Brien challenged Mullin to a fight, writing, "Quit the tough guy act in these senate hearings. You know where to find me. Anyplace, Anytime, cowboy." O'Brien has been a very vocal critic of the senator, repeatedly taking to X (formerly known as Twitter) during the year to call out Mullin's tactics, and both already verbally sparring at a March hearing.

Mullin — a former MMA fighter — then proceeded to challenge O'Brien to fight there and then on the Senate floor. After the two told each other to "stand your butt up," Mullin got up as the chamber shouted for calm, including Sen. Bernie Sanders stepping in to restore order. Several more minutes of slinging insults and challenges ensued, although without any physical altercation. Mullin and O'Brien then appeared to calm down and agree to work out their differences over coffee — a rather anticlimactic ending to a rather tense exchange.