Abolitionists Who Were Murdered For Their Beliefs

They say politics in the United States is more polarized than it has ever been. It seems those on the right and the left no longer agree on anything, and compromise is dead. Maybe it's no surprise considering what the country has been through over the past few years.

If there is one period that could compete when it comes to extreme polarization, it is the time before and during the Civil War. Southern states demanded the right to enslave Black people and to spread slavery into new states and territories. There could be no compromising on the issue of slavery, although the U.S. gave it a try for decades. Either Black people were human, or they weren't. If they were, then slavery was evil, immoral, and reprehensible. The fight between abolitionists and pro-slavery factions was not limited to words. "The Field of Blood" notes that "Many were beaten and bullied in an attempt to intimidate them into compliance, particularly on the issue of slavery." And that's not referring to average Joes on the streets who disagreed: It's talking specifically about the violence that took place between members of the United States Congress.

It was a dangerous time to think Black people didn't deserve to be owned, whipped, and forced to do backbreaking labor. No matter what gender or race you were, demanding freedom for enslaved persons could end in social alienation, physical harm, and, in some cases, even death. These are abolitionists who were killed for their beliefs.

Elijah Lovejoy

People's beliefs on slavery were not simply binary. Even those in the first half of the 1800s who were totally against enslaving Black people believed the solution lay in a variety of different areas, many of which seem pretty horrible today. Elijah Lovejoy was one of the many whose thoughts on what to do about the massive human rights violation changed over time.

According to the Library of Congress, Lovejoy was a newspaper editor and minister. At the start of the 1830s, he felt the best option for enslaved persons was to send them all to Africa. (Amazingly, that was once considered a caring option and not something horrible racists yell at Black people.) Lovejoy's views then evolved to believing enslaved persons should be emancipated slowly over time. Finally, by 1837, he wanted every single slave freed ASAP. And he made sure everyone knew what he thought by writing editorials in the abolitionist newspaper he ran.

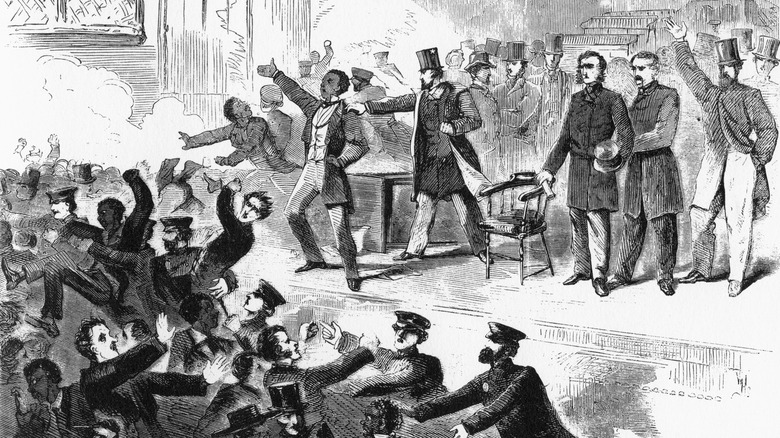

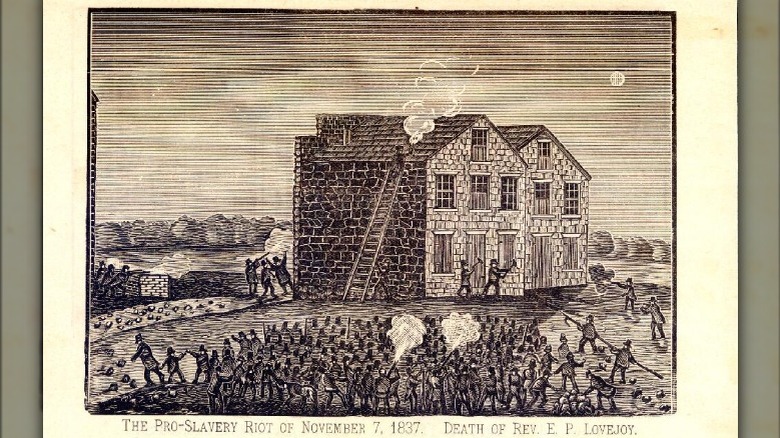

But that newspaper was located in St. Louis, Missouri – and Missouri was a slave state. His press was destroyed by pro-slavery factions multiple times. Lovejoy responded by increasing his circulation. A U.S. senator even opined that Lovejoy's beliefs on slavery were not protected under the First Amendment. When a mob came to burn down the newspaper office on November 7, 1837, Lovejoy ran out to confront them and was shot and killed. His death drew more people to the abolitionist cause, and a young Illinois state representative named Abraham Lincoln made a public statement denouncing the murder.

David Broderick

By 1859, it was clear that the country was ripping apart over the issue of slavery. Political arguments were turning violent, even in the far-flung, brand-new state of California.

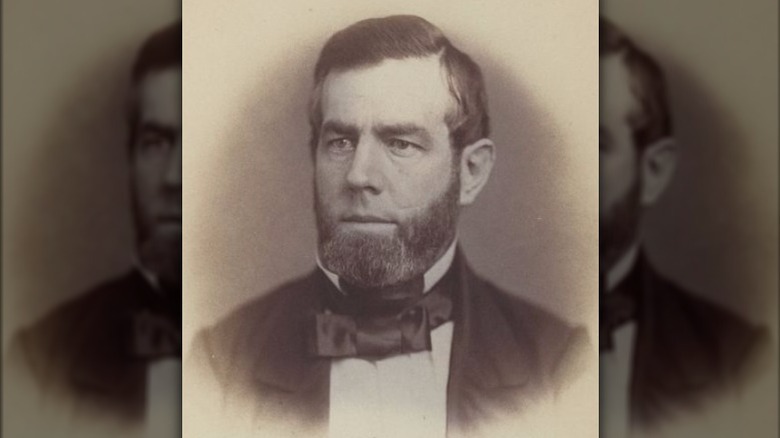

According to the ACLU of Northern California, David Broderick (a U.S. senator, pictured) and David Terry (the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court) hadn't always been at odds. Apparently, they'd actually been friends. But their political differences proved to be too much for their relationship – even though they were both Democrats. Broderick fought to make California a free state, while Terry pushed for it to be a slave state. In the end, the "Free Soil" wing of the party won out, although as the National Parks Service points out, just because owning a person was illegal in California didn't mean Black people had anything even close to equality under the law.

Still, Terry's full-on pro-slavery views eventually lost him re-election. He didn't take this well, blaming his former friend for his defeat. Then the two men started openly insulting each other. Finally, Terry challenged Broderick to a duel. Considering Terry had stabbed a fellow politician in 1856, this was always going to end badly. Their first duel was called off because the crowd was too big, but on September 13, 1859, it went ahead. After Broderick's gun misfired, Terry shot him straight in the chest. It took Broderick three days to die, allegedly saying, "They killed me because I am opposed to the extension of slavery and a corrupt administration."

Seth Concklin

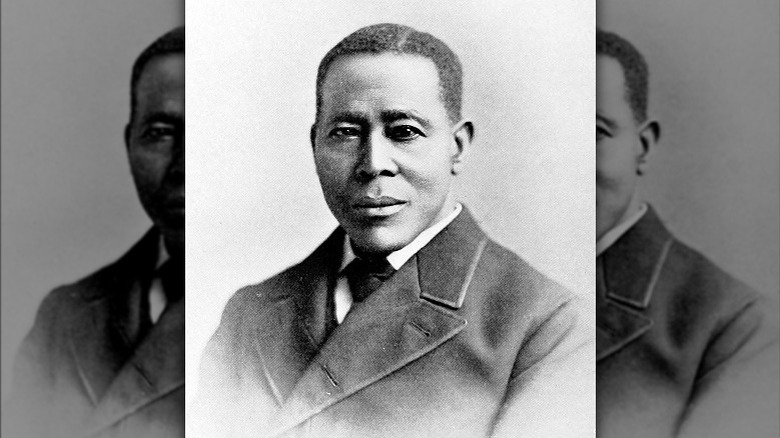

Peter Still's life could easily be a Hollywood film. According to PBS, Peter was born into slavery. Over 40 years, he managed to earn and save up $500 to buy his freedom. Then Peter made it to Philadelphia, where he knew he had family, and he started posting notices trying to find relatives. He went to the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and told his story to a man who worked there – only to discover he was talking to William Still (pictured), the very brother he was looking for.

Peter was desperate to free his wife, Vena, and their children from enslavement, but they were in Alabama and that state made it essentially impossible for an enslaved person to be freed, even if the enslaver was offered a lot of money to do so. With William's help, his brother's story got out, and at least one person who heard it was determined to free Peter's family, no matter what.

Seth Concklin worked on the Underground Railroad, but he didn't listen when told how dangerous this attempt would be. Peter gave Concklin a bonnet of his wife's so she would know the stranger really was sent by her husband. "The Sage of Peter Still" says Concklin managed to get Vina and her three children all the way to Indiana (technically a free state), but there they were arrested. Vina and the children were returned to Alabama, and Concklin was found drowned: he was bound and had been badly beaten up. Somehow, this was passed off as an "accident."

Charles Doy

According to the House Divided Project, in January 1859, 11 enslaved people were running for their lives through Kansas, assisted by three white abolitionists and two free Black men. But "slave catchers" in the area lay in wait for the group's covered wagons to pass, and took them away at gunpoint. One of the white men, John Doy (pictured sitting), would rot in prison until he was convicted for his participation in June. But one month later, John escaped from jail with the help of a group of 10 fellow abolitionists (pictured standing).

One of the men who busted John Doy out was his son, Charles. It wasn't just filial piety that motivated Charles. Like his father, he was a staunch abolitionist. He'd even been driving one of the wagons transporting the "freedom seekers" when his father was arrested, and had also spent time in prison for it. While John managed to escape death on more than one occasion, Charles would not be so lucky.

On July 23, 1860, the New York Times reported that a few weeks earlier Charles Doy had been "Hung By a Pro-slavery Mob." Charles and two others were arrested on trumped-up charges of stealing a horse. One of the men was shot dead but Charles managed to get away ... for a little while. He was soon found hiding in a house by the mob, who then murdered him. The New York Times eulogized that while Charles "defied danger like a hero, he endured suffering with the fortitude of a martyr."

David Walker

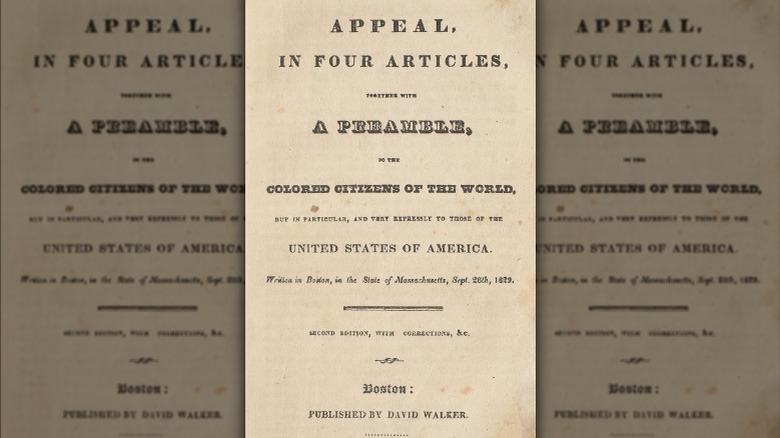

While it could be extremely dangerous for a white person to be outspoken about their abolitionist beliefs, it was even worse for free Black people. David Walker was born to "a free mother and a slave father" in North Carolina in 1785, Documenting the American South records. Walker was born free, a status "inherited" from his mother, but life in a slave state was still horrific for a Black person. He eventually left for the North, saying, "If I remain in this bloody land, I will not live long ... I cannot remain where I must hear slaves' chains continually and where I must encounter the insults of their hypocritical enslavers."

Seeing slavery firsthand made Walker determined to help abolish it. The North Carolina History Project states that once he settled in Boston, Walker gave lectures on the evils of slavery to huge crowds, hid freedom seekers in his home, and "emerged as one of the United States' most radical Black pamphleteers." Walker wanted immediate action. His 76-page pamphlet "Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World" encouraged enslaved Blacks to take up arms in a violent rebellion. And that was just the first printing, as two updated editions published in 1830 were "increasingly militant and inflammatory." His friends told him he was in danger, and to flee to Canada. Blackpast says a huge bounty was placed on his head.

That same year, Walker died suddenly, aged 44. At the time, it was "widely believed" he had been poisoned.

David Starr Hoyt

If you attended an American public high school, you probably learned about Bleeding Kansas. This was a period before the Civil War when the territory of Kansas was created, and lawmakers decided to let the locals determine if enslavement of Black people would be legal there, Legends of America explains. This led to a very violent period, starting in 1854, where many people died. (The most famous abolitionist involved in Bleeding Kansas was John Brown, who later led a botched raid on a federal armory in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, where many people were killed. He was executed for treason.)

Major David Starr Hoyt wanted Kansas to be a free territory and eventually a free state. He'd fought in "every battle" of the Mexican-American War, according to Legends of Kansas, and in 1856, he took his military experience and a few thousand men to the territory to fight for what he believed in. After defending the city from pro-slavery mobs during the "Sacking of Lawrence," Hoyt tried to negotiate a truce with the pro-slavery faction on their own turf at the nearby Fort Saunders. He made it to the fort and allegedly left again, but never arrived back in Lawrence. His mutilated body was discovered a day later.

When Hoyt was murdered, he had a map of the Mississippi River Basin in his pocket. You can see this very map today, complete with large, dark stains of Hoyt's blood, in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

William Hopps

According to the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, Ephraim Nute Jr. was a missionary and "an outspoken and aggressive abolitionist" who was one of the many who moved to the territory of Kansas ready to fight during the Bleeding Kansas period. Nute fought with words, drawing huge crowds to his sermons. He was also a conductor on the Underground Railroad.

In August of 1856, the Reverend Nute's sister and her family came to Kansas from Illinois. His brother-in-law, William Hopps, was not outspoken on abolition like Nute was, but he was related to him and from a free state, which in Kansas at the time was enough to get him killed. "The Incredible Story of Ephraim Nute: Scandal, Bloodshed, and Unitarianism on the American Frontier" records that on August 19, Hopps went out in a buggy and ran into a pro-slavery man named Fugit, who had just made a bet in a bar that he could kill a "Yankee." In front of two children, he did, then mutilated Hopps' body and returned to the bar, announcing, "I went out for the scalp of a damned abolitionist, and I have got one."

The Reverend Nute recorded that this was the third person to be killed after leaving his house in a single week. He wrote to a friend on August 22 and detailed his brother-in-law's murder, as well as mentioning the murder of Major David Starr Hoyt which had occurred less than two weeks earlier. Many eastern newspapers ran articles on Hopps' murder, bringing more people to the abolitionist cause.

Jeremiah Chamberlain

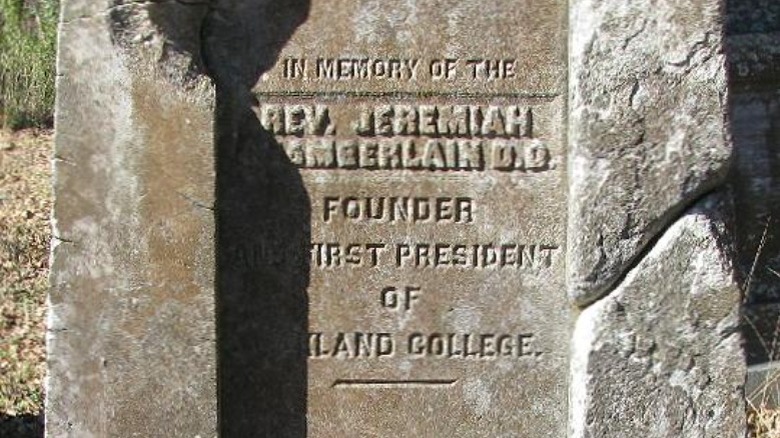

According to the Archives and Special Collections at Dickinson College, Jeremiah Chamberlain was a preacher and missionary who became the president of various colleges throughout the United States, including the first president of Oakland College in Mississippi in 1830. This put him in the deepest of the Deep South for the next two decades, in very different social and political circumstances than he had grown up in outside of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Perhaps because of his Northern upbringing or his religious convictions, Chamberlain was an abolitionist and pro-unionist. This would have been controversial in the area he lived, especially as the country crept closer to Civil War. In 1851, a man named George Briscoe, described as a "local landowner" who was pro-slavery, came to Chamberlain's house on the Oakland College campus. When Chamberlain went out to meet him, witnesses heard an argument and saw Briscoe stab him in the chest. Chamberlain died almost immediately, his wife cradling him in her arms.

It's not known for certain if Chamberlain's anti-slavery beliefs are what got him killed. It's possible that the men had some other beef with each other than no one knew about. But considering the increasingly fraught relationship between abolitionists and pro-slavery supporters in 1851 Mississippi, Chamberlain's outspoken beliefs are the most likely explanation. The evidence even led Oakland College's 1905 Alumni Directory to label the murder an "assassination." The motive was never known for certain, however, because Briscoe fled and died by suicide while hiding from the law.

Joaquim Firmino de Araújo Cunha

For some pro-slavery individuals, even being roundly defeated in the Civil War wasn't enough for them to accept that it was over, that Blacks were people, that their side had lost both morally and literally. But the U.S. was not the only place in the world where white people could own Black people. According to the Economist, after the war, thousands of disgruntled Southerners looked even further south, to Brazil. One of these was James Warne, a doctor who'd fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War, who moved to South America in 1866, just eight months after the fighting ended.

But Brazil was also looking to put an end to the evil of slavery. Many in the country were working towards abolition, and by the end of the 1880s, it looked like they would be triumphant. But the law still required police to arrest "runaway slaves," the BBC Brazil explains, and to put down any demonstrations against slavery. But in one town, the police chief Joaquim Firmino de Araújo Cunha refused to do any of that, and instead assisted enslaved people in their escapes, including hiding them in his own home.

This made the pro-slavery faction homicidally angry. On February 11, 1888, a mob of an estimated 200 people, led by Dr. Warne, surrounded Firmino's home. He tried to escape by jumping out a window but fell to the ground where he was beaten to death.

The murder was international news. Three months later, Brazil banned slavery.

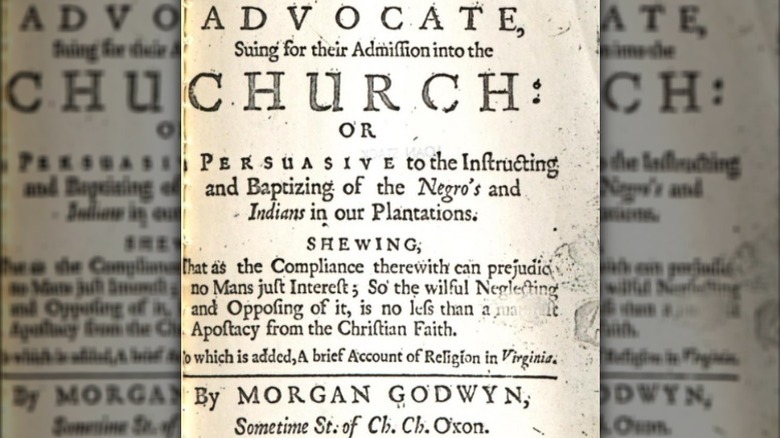

Morgan Godwyn

The debate over enslaving Black Africans did not start in the mid-1800s. As far back as 1685, the minister Morgan Godwyn was openly preaching against the slave trade in London's St. Paul's Cathedral, according to The Mysterious Disappearance of Morgan Godwyn: Rethinking Press Censorship and the Debates over Slavery in the Early British Empire. Since that was nearly 200 years before the U.S. Civil War, you know he wasn't successful in convincing the British to stop the atrocity.

But Godwyn was very determined. He published multiple books on the evils of enslaving people. "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition" records that he called their horrible situation a "Soul-murthering [sic] and Brutifying-state of Bondage." He railed against the "hellish principles" that kept Blacks enslaved, especially when people tried to use the Bible as justification. Godwyn practiced what he preached (literally), heading to Virginia and Barbados to minister to enslaved people. Perhaps realizing that abolition was nowhere near, he tried to get enslavers to at least allow Blacks to have Christian instruction and religious services. At the time, even this was too radical for most.

Godwyn's final book, published in 1685, straight-up called out those who were pro-slavery for putting money over the teachings of Jesus. Then he disappeared. There is some mystery surrounding exactly what happened to him, although "The Slave's Cause" unequivocally states, "Godwyn was murdered for his antislavery views." Considering his activism and the trouble he'd been in before, this is certainly a likely outcome.