Things People Believed 25 Years Ago That Ended Up Being Wrong

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In the early 1990s, people watched Bill Cosby portraying a devoted husband and beloved family man on The Cosby Show. Michael Ovitz was one of the most powerful executives in Hollywood, and he would seemingly rule forever. And the idea of the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox ever winning a World Series seemed impossible. Let's look at some other things commonly believed back then that turned out to be wronger than wrong:

People believed it was the end of history

As the Cold War was ending, philosopher Francis Fukuyama asked in the title of a 1989 National Interest article if it was "The End of History?" He wrote in the essay that the end of the Cold War could also bring the "final form of human government," a nicer democracy. He expanded on the idea in his 1992 book and removed the question mark from the title, calling it The End of History and the Last Man.

The book was enormously influential at the time. As The Atlantic described the argument, "Democracy would win out over all other forms of government," countries would have to "embrace some measure of capitalism" in order to survive, and this would "invariably demand greater legal protection for individual rights."

Spoiler alert: not even close. As The Atlantic says, "It's hard to imagine Fukuyama being more wrong. History isn't over and neither liberalism nor democracy is ascendant ... most disturbingly, the connection between capitalism, democracy, and liberalism upon which Fukuyama's argument depended has itself been broken." So basically, Fukuyama's "End of History" idea was wrong about everything. But it wasn't the end of his career — he still gets quoted as an "expert." Must be nice.

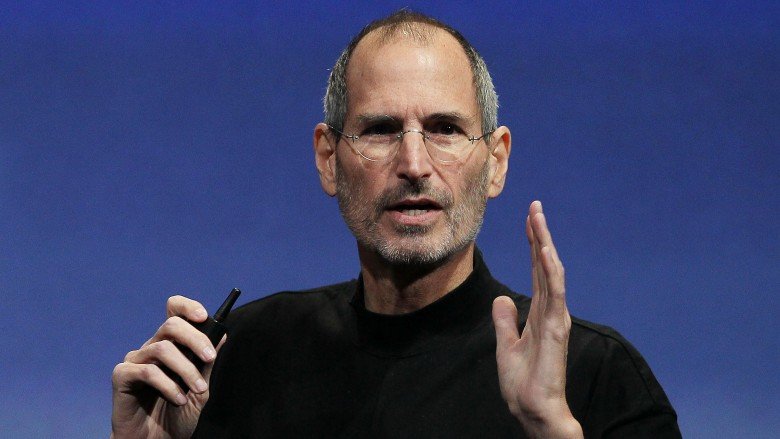

Steve Jobs was a has-been

When Apple co-creator Steve Jobs died of cancer in 2011, he was compared to Thomas Edison as an authentic American genius. Jobs had disproved F. Scott Fitzgerald's adage that "there are no second acts in American lives"; after some wilderness years, Jobs had one of the best second acts ever. If Jobs had passed away in 1992, he'd likely be perceived as a failure.

Let's backtrack. Jobs co-founded Apple Computers with Steve Wozniak in a garage in 1976 but was forced out of his own company in 1985. After that, Jobs started NeXT Computers. The company sold wildly expensive computers — up to $9,500, according to The New York Times. Over seven years, they sold maybe 50,000 units. And Jobs micromanaged everything, even the landscaping, before finally giving up on making computers in 1992 and focusing on software instead.

Apple had a disappointing time without Jobs. Its 1992 Newton PDA was a disappointment, and Apple faced big competition from Windows 95. When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company held just 4.4 percent of the U.S. market. Jobs' return to Apple obviously worked out well for all parties. Yet those "wilderness years" ended up changing Jobs for the better — he managed Apple in a far superior way when he returned. If he hadn't come back at all, we might not even remember him today.

D.A.R.E. scares worked

If you were a '90s kid, you likely participated in the D.A.R.E (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program. A friendly cop would lecture your class on the evils of drugs and alcohol, the idea being that such "straight talk" would steer children clear of addiction and other terrible choices. Unfortunately, a cop daring you to resist drugs was about as effective as Mr. Mackey mumbling "drugs are bad, m'kay."

In 1999, the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology published a study bluntly titled "Project DARE: No Effects at 10-Year Follow-Up." Its results? D.A.R.E. kids were no more or less likely to abuse drugs than those who never did the program. What's more, the study linked D.A.R.E. to lowered self-esteem, noting that sixth graders in the program often felt worse about themselves ten years later than those outside the program. As Time explained in 2001, kids don't typically handle hyperbole and fearmongering statements well, and '90s D.A.R.E. was all about that. Kids hear drugs and addiction are everywhere, so they feel worse about themselves and the world around them.

D.A.R.E. is still around, albeit in a much different form that stresses a more evidence-based approach. Whether it works or not remains to be seen, though it would be difficult for it to be worse than the version we got in the '90s.

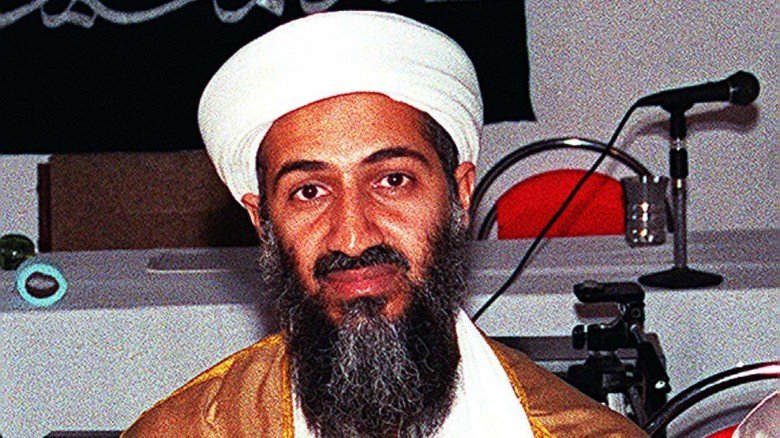

Osama bin Laden was a freedom fighter and peacemaker

Yes, there was a time when people didn't think of mass casualties when hearing Osama bin Laden's name. In 1993, Robert Fisk of The Independent wrote a very positive article about him with the headline "Anti-Soviet warrior puts his army on the road to peace." The article said that "With his high cheekbones, narrow eyes, and long brown robe, Mr. bin Laden looks every inch the mountain warrior of mujahedin legend. Chadored children danced in front of him, preachers acknowledged his wisdom." Yep, the guy behind 9/11 basically got a Tiger Beat writeup.

Bin Laden came from a wealthy family with a construction business. He went to Afghanistan to fight against the Soviets after the Russians invaded in 1979 and got involved with the mujahedin, considered "freedom fighters." Bin Laden was indirectly funded by the CIA. NBC News said that, "by 1984, he was running a front organization known as Maktab al-Khidamar — the MAK — which funneled money, arms and fighters from the outside world into the Afghan war."

The Guardian wrote in 1999 that while "it is impossible to gauge how much American aid he received," it is estimated that plenty of foreigners learned "bomb-making, sabotage and urban guerrilla warfare in Afghan camps the CIA helped to set up." However, the article said that it wasn't just about bin Laden here: "The point is not the individuals. The point is that we created a whole cadre of trained and motivated people who turned against us. It's a classic Frankenstein's Monster situation." And bin Laden ended up being the biggest monster of all.

A low-fat diet with lots of carbs is the key to dieting

In 1992, the Food and Drug Administration unveiled a food pyramid to explain to Americans what they should eat. The bottom of the pyramid suggested eating 6-11 servings a day of carbs; "fats and oils" should be "used sparingly." Meats and nuts, meanwhile, should only comprise two or three servings a day. This super-high carb, very low-fat diet was considered the way to good health and losing weight.

One of the biggest figures in pop culture at that time pushing this sort of diet was Susan Powter. She had white-blonde, super-short hair and exaggerated eyebrows, and she was big in the 1990s with her "Stop the Insanity!" weight loss crusade, which emphasized a low-fat diet with lots of carbs."It's not food that makes you fat. It's fat that makes you fat," she insisted. She was wrong — it's a lot of other stuff that makes you fat. Time wrote that her diet "caused a run on processed low-fat food like SnackWells and frozen yogurt. But those treats, it turned out, were chock-full of sugar and a whole mess of calories. Result: you gained weight."

Since then, the FDA has made several revisions to its food recommendations, most recently with MyPlate in 2011. This new stab emphasizes veggies and fruits, suggests reducing your carb/grain intake, and make little mention of avoiding fat. There was also a National Institutes of Health study in 2014 that showed people lost more weight (and body fat) on a low-carb diet than a low-fat one. The idea of filling up on white bread, rice, and cereal — as the original food pyramid had — is completely outdated. So don't stop the insanity — stop the unlimited breadsticks at Olive Garden.

Killer bees will kill us all

Most people know nowadays that bees are really important to our ecosystem. In fact, there is concern that too many bees are being killed off thanks to "pesticides, parasites, disease and habitat loss," according to the BBC. That's because bees pollinate a lot of the food we eat. And then there's the delicious honey and (less-delicious) wax that can be used to make candles.

But in the early 1990s, people feared bees, specifically the dreaded "Africanized honeybees." According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, they were brought to Brazil in the '50s with the idea that they'd be suited to the South American climate. The bees were ultimately called "killer bees" and swarmed around the world until arriving in the U.S. in 1990.

When they arrived in the U.S., a couple people died after disturbing large colonies, and concern grew that the bees would kill many more people. As the BBC noted, the reputation of killer bees was that they were "huge and are equipped with lethal venom." However, the reality was that "killer bees are actually smaller than regular honeybees" and "their venom is also less powerful." The main difference is that they're more likely to sting and pursue targets for longer distances than regular bees do. But the killer bees were never the threat they seemed to be based on horror movies like The Swarm.

Cities will continue to decay as people flee for the suburbs

There are a lot of complaints these days about gentrification — the idea of wealthy people renovating and revitalizing forgotten, crime-ridden urban neighborhoods. Ultimately, with more affluent people moving in and rents going up, longtime residents can't afford their own homes. Some of the negative effects of this have been overblown, according to The Washington Post. But 25 years ago, the idea of gentrification was a mere pipe dream. The standard attitude then was that suburban growth, which started after World War II and accelerated in the 1960s and 1970s, would leave the cities bereft forever.

A 1990 report by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress didn't think things would ever change in the next 25 years. A tangible symbol of how bad cities had gotten was Times Square, once the place to be in the city. Then it became a nightmarish dump, filled with urban squalor and porn. In the early 1990s, the idea of fixing it seemed impossible. ”It wasn't so much that it was scary,” David L. Malmuth, a Disney filmmaker, later told the The New York Times. ”It was dead. It was this odd street in the center of the city where there was almost no life.”

The New York Times described Disney's early '90s attempts at redevelopment of Times Square as being "the first tangible sign that the long-awaited redevelopment of a tawdry stretch of Eighth Avenue is more than a pipe dream." The change of Times Square was a symbol that cities weren't dead and that putting money and effort into change could actually have tangible results. It was a microcosm for how cities became hot again.

Russia would become a healthy democracy

After the Soviet Union's 1991 collapse, it seemed Russia was done. As Hendrik Hertzberg reported for the New Republic in 1992, he could purchase neckties for a nickel each and lunch for three for $0.38. That bodes not well for a nation's health. The World Bank backs this up — it says Russia's gross domestic product (GDP) was $506 billion in 1989. By 1992, it had fallen to $460 billion, and by 1999, it was just $196 billion.

The solution, in many people's eyes, was to democratize Russia. According to Stephen Cohen's 2001 book Failed Crusade: America and the Tragedy of Post-Communist Russia, the Clinton administration attempted to turn Russia toward capitalism and democracy. As Vice President Al Gore explained in 1999, "Our policy toward Russia must be that of a lighthouse. ... They can locate themselves against this light." In other words, if America guides Russia toward the "right" path, all will be well.

That ... didn't work. According to Cohen, a U.S.-style Russia was a crashing failure. The economy improved a bit, but not enough. In fact, this attempted transition begat "more anti-Americanism than [Cohen] had personally ever observed." According to Alfred B. Evans' 2011 essay The Failure of Democratization in Russia, it wasn't until Russia adopted a "semi-authoritarian" approach in the 2000s that the country's economy started to recover. So the economy came back, but it wasn't because of democracy.

You could retire early if you invested in comic books

There was once a time where buying comic books as an investment was a big thing — it was assumed that the value would always go up. The Weekly Standard noted that Action Comics #1, the first comic book with Superman, was worth $400 in 1974. By 1984, the value had shot up to $5,000, and by 1991, it was going for $82,500. That wasn't the only comic book increasing in value. Detective Comics #27, Batman's debut, sold for $55,000 in 1991.

Comic books were becoming a big investment as "stores were popping up all across the country to meet a burgeoning demand." Because of this, "even comics of recent vintage saw giant price gains," where a "comic that sold initially for 60 cents could often fetch a 1,000 percent return on the investment just a few months later." Sadly, this was a bubble that peaked in 1992, collapsing not long thereafter. Greater demand decreased the rarity. In addition, the market became flooded with tons of new comics, plenty of which just sucked.

Ultimately, the "the Golden Age glamour books" from the earlier days of comic books came back a little, the piece notes, but the ones from the '80s and '90s never really did. These days, comic books are considered "loss leaders," with the real money coming from comic movies, TV shows, toys, amusement parks, and all the rest. That mint Age of Apocalypse #1 you've kept in a baggie for 20 years? Good luck fetching even a fiver for it.

AIDS will get worse

One of the most shocking announcements in sports happened in 1991, when Magic Johnson revealed he was HIV-positive and was retiring from the Lakers immediately. Journalists were so stunned by the news, according to PBS's Frontline, that some of them cried.

Contracting AIDS then was considered to be a death sentence. It was also considered to be a gay disease. So Johnson revealing he, as Frontline put it, "admitted to having contracted the disease from unprotected heterosexual sex" was a real shocker. It seemed, then, like AIDS was going to continue to be an epidemic that would get worse and worse.

However, over 25 years later, not only is Johnson still alive, but he's healthy as a horse. AIDS, meanwhile, would become a treatable disease in the United States, thanks to what was called the "triple cocktail" of drug therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control, about 1.2 million people in the U.S. are living with the disease, and the number of diagnosed cases declined 19% from 2005 to 2014. While people still do die from AIDS, it's no longer the automatic death sentence it once was.

Crime would continue to be on the rise, thanks to superpredators

Crime was a huge issue in the early '90s, with people being concerned about "superpredators." As The New York Times put it in 2014, the idea of superpredators was "based on a notion that there would be hordes upon hordes of depraved teenagers resorting to unspeakable brutality, not tethered by conscience." There was talk by criminologists like James A. Fox, that a "blood bath of violence" was going to destroy the country. John DiLulio, Jr. was a political scientist who warned then that "the rash of youth crime and violence" was hurting the inner city, and that "other places are also certain to have burgeoning youth-crime problems that will spill over into upscale central-city districts, inner-ring suburbs, and even the rural heartland." He insisted then that "all of the research indicates that Americans are sitting atop a demographic crime bomb. And all of those who are closest to the problem hear the bomb ticking."

So you may be wondering why we're not a 24/7 cesspool of death and crime. Well, as The Times noted, the whole "superpredator" thing was total hokum. Instead, crime dropped rapidly, and America became safer. The superpredator notion was so dispelled, in fact, that Hillary Clinton using that word in a '90s speech was brought up against her during her 2016 presidential campaign.

Power lines cause cancer

In the early '90s, there was concern that living near power lines was detrimental to one's health. Specifically, the electromagnetic fields emitted from these high-voltage lines were supposed to cause cancer, especially in children. Ted Koppel once said on ABC's Nightline (via Gizmodo) that "The potential danger from EM fields is making millions of human beings into test animals."

Then there was the New York Times, who wrote that "palpable dread gripped parts of the country after reports that clusters of cancer had developed among children whose families lived near high-voltage power lines." Ahhh! Power lines bring death! Well ... not really. Studies done in the 1990s, when looked at later on, proved that there was no real risk. John Moulder, an expert in the field, told RetroReport in 2014 that "no one has found a way that power line fields can do anything at all to cells or animals ... there's no way it can cause cancer."

Yet despite this, the fear of power lines still persists with some people. Moulder explained, "Once something like this becomes part of our collective memory, there is no way to remove it from that memory." Alternative fear-facts? It would appear so.