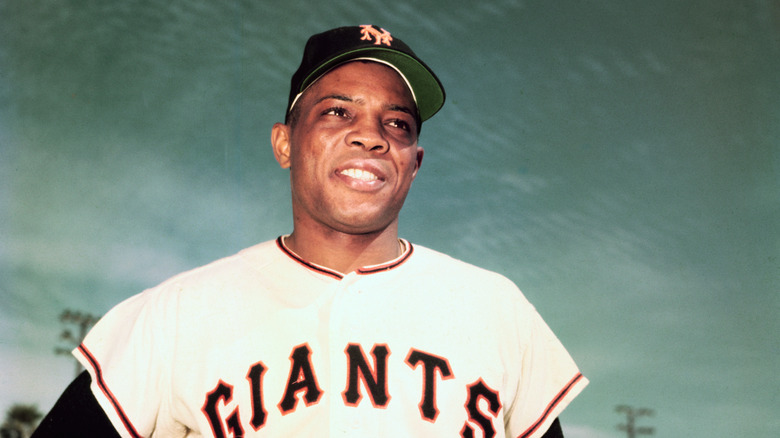

Baseball Legend Willie Mays Dead At 93

Baseball legend and candidate for all-around greatest baseball player who ever lived, Willie Mays, died on June 18, 2024 (via San Francisco Chronicle). He was 93 years old.

On one hand, we can talk about Willie Mays' skill and legacy in terms of numbers: 2,062 runs, 3,283 hits, 660 home runs, 1,903 runs batted in, a .302 batting average, Rookie of the Year in 1951, Hall-of-Fame inducted in 1979 (all per the MLB), two-time National League MVP, 24-time all-star, once for each year he played, two-time All-Star MVP, 12-time Gold Glove (these latter per the Baseball Hall of Fame), and on and on it goes.

These impressive figures, on the other hand, reveal only part of the story. Mays didn't just bring his a nigh-magical set of offensive and defensive skills to baseball, he brought a down-to-earth charm, charisma, and joy that made a game what it ought to be above all else: fun. Footage on YouTube shows Mays heading out into the streets after games to play stickball with neighborhood kids, "swatting a rubber ball with a broomstick, kidding with the crowd," and encouraging and instructing the next generation. The "Say Hey Kid" was just as chatty on the field, conjuring friendships amongst competitors as often as he did admiration amongst fans. Far beyond his stats, this is what made Mays a legend.

Born into an athletic family and gifted from a young age

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born into an athletic family in 1931. His father, Willie "Cat" Sr. was a semi-pro baseball player and center fielder like his son, and his mother was a high school sprinting champion, as Notable Biographies tells us. Mays was basically surrounded by baseball from infancy. His father, after divorcing from his mother when Mays was 3 years old, taught him the basics off the field, and let his son sit in the dugout during Birmingham Industrial League games.

By age 13, Mays was playing on a semi-professional team called the Gray Sox. From 13 to 16, as Biography says, he also played on the Fairfield Industrial High School basketball and football teams. At age 16, he entered what was called "The Negro League," the national professional league for Black people, as center fielder for the Birmingham Black Barons. There, he earned far more than he could otherwise: $250 a week. He was also able to finish high school.

A scout for the New York Giants, one of the newly "integrated" teams (Black and white people combined), visited a Black Barons game and was captivated by Mays. In 1950, Mays joined the minor leagues on a $4,000 bonus and $250 a week salary, and by the end of 1951, Mays had already made his way up to starting center fielder in the majors for the New York Giants themselves.

A lasting legacy that continues to inspire

Many of Willie Mays' career highlights can be watched in compilations on YouTube. "The Catch" in 1954 — an over-the-shoulder deep catch and second base throw — is still regarded as possibly the greatest defensive play in the history of baseball. As Mays himself says on YouTube, his father told him that "defense is the No. 1 thing in baseball," and Mays' goal was always to play defense better than offense. Nonetheless, fans went to Giants' games expecting not only to be wowed by center field acrobatics, but by home runs and fleet-footing base running. Mays always wanted to leave the crowd satisfied, saying that if people paid money, he should try to put in "110%." All of this while he missed nearly two years of his career due to military service, from 1952 to 1954, as USA Today says.

Mays used the coronavirus pandemic to finish his 2020 memoir, "24: Life Stories and Lessons from the Say Hey Kid," which he wrote with friend and baseball columnist John Shea. "Baseball is his whole outlet," Shea said on The New York Times, "his way to express himself." Mays was a regular at Giants baseball games throughout his life, making connections and brightening rooms wherever he went. "My thing is keep talking and keep moving," he said.

Mays is survived by one son, Michael. His wife Mae Louise Allen passed away from Alzheimer's-related complications in 2013.