The Most Dangerous Dinosaurs To Ever Exist

Picture this — it's 1676, and you're a museum curator in England tasked with identifying a huge, strange-looking "stone" that someone found in a limestone quarry. It looks like a bone to you — specifically, half of a femur — but it's way too big to belong to any animal you're familiar with.

To his credit, Robert Plot figured out that he was actually looking at a petrified bone. However, since no one had heard of dinosaurs at the time, he suggested that it belonged to a giant human, as in the biblical sort. Over 80 years later, physician Richard Brookes made an even ballsier move — noticing the bone fragment's resemblance to a pair of testicles, he gave it the totally mature scientific name Scrotum humanum. It took 61 years before paleontologist William Buckland could give it a proper name (Megalosaurus), ending its whirlwind journey towards becoming the first non-avian dinosaur to receive a valid name.

Since then, scientists have come a long way from naming prehistoric predators. Experts now know, for example, that the "terrible lizards" called dinosaurs weren't really lizards. In fact, they're more closely related to birds, which are technically living dinosaurs. They also know from fossil analysis that quite a few of these animals were indeed quite terrible. Here are some of the most dangerous non-avian dinosaurs to ever roam the planet. (Sticking strictly to extinct dinosaurs, of course. Otherwise, birds like the cassowary would have a decent shot at making this list.)

Tyrannosaurus rex: the tyrant lizard king

Arguably the most popular prehistoric predator ever, Tyrannosaurus rex is typically the first animal that comes to mind when anyone hears the word "dinosaur." Its existence marked the end of an era for Earth. It was among the last non-avian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event wiped them out.

Based on what paleontologists can tell from fortuitously well-preserved fossils — including the remarkably complete "Sue" and "Stan" (via National Geographic) — T. rex lived up to its ferocious name. A 2009 analysis of T. rex showed that it was probably able to move its eyes and head rapidly and fluidly, hear low-frequency sounds, and even smell food from a distance akin to modern vultures. And as Gizmodo reported in 2014, it could likely see as well as, or even better than, today's birds of prey. According to Smithsonian Magazine, T. rex's maximum bite force reached almost 12,800 pounds, the most powerful bite of any land animal to ever exist. Or, as National Geographic put it, its mighty maw could crush a car or hoist multiple pick-up trucks.

It's no wonder paleontologists call T. rex the apex predator of its time. Virtually every part of its (possibly feathered) ancient anatomy could have made it an efficient killing machine. Research from 2017 suggests that even its relatively small and oft-mocked arms, which featured sickle-like claws, were probably strong enough to cause deep wounds up close.

Spinosaurus: the snouty, sail-backed swimmer

Most people probably know Spinosaurus as the dinosaur from "Jurassic Park III" that made short work of T. rex (via Cinema Blend). Much of that interpretation of the sail-backed dinosaur turned out to be scientifically inaccurate, though. Spinosaurus was indeed a massive Mesozoic threat but in an entirely different manner from its Hollywood depiction.

Ernst Stromer described the first (and at the time, only) known Spinosaurus remains in the 1915. Twenty-nine years later, during World War II, a bomb destroyed them, leaving only Stromer's drawings intact (via National Geographic). Spinosaurus remained a mystery for decades, until the description of new specimens in the late '90s and early 2000s allowed scientists to further study this bizarre dinosaur. Experts now know that Spinosaurus was among the largest meat-eating dinosaurs ever (over 49-feet long, based on recent estimates), and that it likely led an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle, as reported by Sci-News. Digital analysis of its fin-like tail revealed that Spinosaurus could have used it like a paddle, swimming with wide feet and nabbing prey with its narrow, sharp-toothed snout — a prehistoric "river monster" unlike any other dinosaur science knows of.

However, scientists still are not sure why it had a massive back sail. Previously, scientists suggested that it was for body temperature regulation, energy storage, scaring enemies, or attracting mates. A newer idea is that Spinosaurus could have used it to herd prey into a "bait ball," akin to sailfish and thresher sharks (via Cambridge University Press).

Utahraptor: the plunderer from Utah

Another iconic but inaccurately portrayed dinosaur from the "Jurassic Park" franchise — and perhaps the most popular one — is Velociraptor, a human-sized, hyper-intelligent hunter with scaly skin and sickle-like foot claws. In reality, Velociraptor was turkey-sized. According to Yale News, author Michael Crichton depicted a different dinosaur, Deinonychus, but used Velociraptor's "more dramatic" name. Interestingly, just before the 1993 release of "Jurassic Park," paleontologists in Utah stumbled upon what the filmmakers had envisioned — a super-sized version of Velociraptor (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Utahraptor is the largest-known member of the Dromaeosauridae family (which Velociraptor and Deinonychus are both part of). Its name honors John Ostrom and Chris Mays, two significant figures in Utahraptor's discovery. Experts say it could have reached a maximum length of 23 feet and could have weighed over 600 pounds. This big, bulky dromaeosaurid probably sacrificed speed for stability. It was likely an ambush hunter that delivered stronger kicks, picked larger targets, and relied heavily on its massive jaws to kill its prey. In many ways, it was akin to a smaller tyrannosaurid.

As fossil evidence shows older dromaeosaurids sporting feathers, it's almost certain that Utahraptor was covered with feathers, too. And if that makes Utah's state dinosaur sound less intimidating than the raptors of "Jurassic Park," take a minute to picture a ginormous, muscular murder chicken inching menacingly towards you, its foot sickles ready to deliver some disembowelment. Trust us, you'd be too busy running to laugh.

Allosaurus: the strange, delicate lizard

If the Cretaceous period had T. rex, the Jurassic period had Allosaurus. According to LiveScience, Allosaurus was likely powerful enough to take down dinosaurs that were nearly thrice its size.

Amazingly, a 2015 study found that Allosaurus could open its jaws nearly 16 degrees wider than Tyrannosaurus rex, In addition, Allosaurus had serrated, dagger-like teeth that curved backwards, likely to prevent its unfortunate prey from getting away (via the National History Museum). Meanwhile, a 2002 CT analysis of a cast of an Allosaurus' braincase showed striking similarities with crocodilian brains. It also suggested that Allosaurus may have had a particularly good ear for low-frequency sounds and was probably keen at detecting (but not necessarily evaluating) smells.

While Allosaurus was one of the most successful predators of its time, fossil evidence suggests that it wasn't above hunting — or even scavenging the corpses of — its own kind during lean times (as reported by ABC News). Still, experts regard Allosaurus to have been an active hunter, as evidenced by bones that sustained damage from what was likely a Stegosaurus defending itself with its spiky tail (via Smithsonian Magazine).

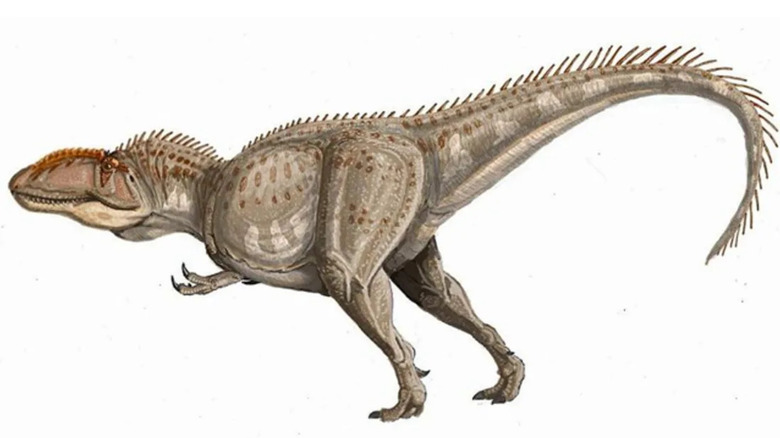

Majungasaurus: the (possibly cannibalistic) lizard from Mahajanga

A ferocious Cretaceous-era carnivore, Majungasaurus' freakishly shaped skull highlights this dinosaur's most noteworthy feature – sharp, serrated teeth. A fairly recent study, as per the American Association for the Advancement of Science, revealed that Majungasaurus regrew its teeth up to 13 times the rate of an average carnivorous dinosaur, kind of like how sharks lose their teeth and constantly grow new ones throughout their lifetime. According to experts, this could be explained by bone-gnawing tendencies. Majungasaurus could have chewed them up to get whatever nutrients it lacked.

Interestingly, it's also one of the few non-avian dinosaurs whose fossils strongly suggest cannibalistic behavior. In a 2007 paper, researchers noted that many Majungasaurus bones featured tooth marks that were similar to the ones seen on various sauropod (long-necked) fossils. Furthermore, the spacing, size, and serration marks on said fossils matched Majungasaurus' teeth quite nicely.

Like its other meat-eating relatives, Majungasaurus had one more noteworthy and somewhat ridiculous characteristic — its short, stubby arms that featured small, paddle-like hands that it probably didn't (or couldn't) use for grabbing prey (via LiveScience). Regardless, not even its comically tiny guns could stop toothy, short-snouted Majungasaurus from becoming the top predator of Mesozoic-era Madagascar.

Giganotosaurus: the sprinting, slicing meat-eater

When paleontologists first described it in a 1995 paper, they thought that the approximately 41-foot-long Giganotosaurus was the largest meat-eating dinosaur that ever lived. And while experts now know that Spinosaurus was longer by a few feet, that doesn't make Giganotosaurus any less impressive (or dangerous). In fact, its sheer size meant that it was the top dog of its ecosystem.

One of Giganotosaurus' most noteworthy features is its thin, pointed tail. LiveScience explained how experts saw this as a hint of this gigantic predator's surprising agility — it could have acted as a stabilizer of sorts, maintaining the ferocious meat-eater's balance as it made sharp turns and chased after its prey. With its strong legs, scientists estimate that it could have reached a top speed of 31 mph while sprinting (compared to T. rex's approximate maximum running speed of 25 mph). Interestingly, some experts argue that Giganontosaurus could maintain its own body temperature regardless of its environment (and grow really fast).

Due to its relatively weaker bite force than T. rex's, Giganotosaurus likely took down its prey by slicing its target's flesh, wounding its prey, and wearing it down to the point where the predator could easily overpower it.

Ankylosaurus: a tank with a built-in wrecking ball

Were you expecting this list of dangerous dinosaurs to feature meat-eaters from start to finish? Ankylosaurus, the dinosaur equivalent of a tank fused with a wrecking ball, would probably beg to differ.

Among all the armored dinosaurs paleontologists have identified so far, Ankylosaurus is one of the largest, clocking in at about 20.5 feet, according to a paper published in 2004. The distinctive bony knobs and scutes (also called osteoderms) adorning Ankylosaurus' back makes it one of the most easily recognizable dinosaurs in popular culture. Based on LiveScience's description, Ankylosaurus' oval-shaped scutes formed within its skin and were probably covered with keratin, the same material that makes up human fingernails and rhinoceros horns. Bony plates and spikes formed rows running down Ankylosaurus' hips and back and likely extended to its legs and tail. It even sported a pseudo-helmet of plates and horns, protecting its head and eyes.

Apart from its natural armor, though, what truly made Ankylosaurus a formidable foe was the massive club at the tip of its tail. Based on modern estimates, the massive, fused bone club could have been powerful enough to break an attacker's legs. In fact, the Redpath Museum features a specimen of Gorgosaurus, a meat-eating dinosaur, with a right leg that apparently broke and healed while it was still alive. It's believed that an Ankylosaurus left that carnivore with a (literal) lasting impression.

Argentinosaurus: the long-necked Argentine giant

The second plant-eater on this list, Argentinosaurus, is here because of one big reason — it was, well, big. In fact, it may have been one of, if not the biggest land animal to walk the planet. Since paleontologists have yet to find a complete Argentinosaurus skeleton, they had to work with whatever remains were available, as explained in a Phys.org article. Using some vertebra and leg bones, experts were able to estimate the late Cretaceous long-neck's length and weight — roughly 119.75 feet long and approximately 100 tons.

SyFy Wire speculated that super-sized sauropods like Argentinosaurus were able to thrive precisely because of their immense bulk. After all, since it would take even a large-sized meat-eater like Tyrannosaurus or Giganotosaurus too much time and effort to take down a single sauropod, it makes sense that they'd go after smaller, easier targets instead.

And of course, there's the possibility of getting crushed under Argentinosaurus' massive foot. In 2019, researchers described a rare fossil find from the Jurassic period — a prehistoric turtle seemingly squished by a sauropod (via Scientific American). Now imagine what an Argentinosaurus' foot could do.

Mapusaurus: the meat-eating Earth lizard

Being super-sized didn't automatically mean that dinosaurs like Argentinosaurus were completely safe from other dinosaurs that wanted to eat it for lunch. Meet Mapusaurus, the massive meat-eater that experts believe was bold enough to hunt and feast on Argentinosaurus and other huge dinosaurs.

ABC News reported that when paleontologists unearthed the remains of this 40-foot-long predator in a bone bed in Argentina, they actually found several individuals, including a few younger ones, grouped together. While it's possible that the corpses just ended up getting deposited there by a seasonal stream, some experts have suggested that this could be the first evidence of social behavior among meat-eating dinosaurs.

Given how it probably would have required a bit of teamwork to take down a titan like Argentinosaurus, the idea of Mapusaurus hunting in packs isn't that far-fetched. As paleontologist and co-discoverer Phil Currie told ABC News, "Carnivores, when you find them all together like this, were probably packing animals with coordinated hunting efforts."

Carcharodontosaurus: the shark-toothed lizard

The mere thought of a shark can make people feel extremely terrified and uneasy. This is largely thanks to how pop culture has depicted the marine macropredator over the years (looking at you, Steven Spielberg). It's not really that surprising, then, that a dinosaur with teeth similar to a great white shark's would end up being named after it.

A 2019 article on Reuters described Carcharodontosaurus as one of the best-known species of its group — and as it turns out, there's a good reason behind its shark-like chompers. As paleontologist Soki Hattori explained, "The teeth of carcharodontosaurs, including Carcharodontosaurus, exhibit characteristic undulations of the surface along the margin of the thin, blade-like 'shark-tooth.'" This means that these predators were likely able to tear the flesh off their targets with minimal effort.

Aside from its size and terrifying teeth, experts like Donald Henderson of the Royal Tyrrell Museum say that Carcharodontosaurus also had strong jaws and neck muscles (working in conjunction with its center of mass) going for it. Henderson shared in an interview with Inverse that at least one particular species of Carcharodontosaurus, C. saharicus, could have lifted an animal weighing up to 935 pounds in its mouth. (For a bit of perspective, that's about three dirt bikes!)

Tarbosaurus: Asia's answer to T. rex

People tend to describe Tarbosaurus as the Asian counterpart of T. rex, and they're not exactly wrong.

In 2012, LiveScience laid out some of the key differences between the two closely related dinosaurs. For starters, Tarbosaurus grew up to almost 40 feet long, which is about 5 feet shorter than the largest T. rex specimen. Furthermore, Tarbosaurus' arms were even shorter than its North American relative's. In fact, the Australian Museum's dedicated Tarbosaurus page states that the creature had "the smallest arms of any large tyrannosaur relative to its body size." A 2003 paper also compared the two meat-eaters' skulls and found that Tarbosaurus had a narrower skull, a more rigid lower jaw, and more teeth.

That said, you certainly shouldn't dismiss Tarbosaurus. Experts say that like its more popular cousin, Tarbosaurus sat at the top of the late Cretaceous food chain in Mongolia. Interestingly, fossil analysis revealed that Tarbosaurus could likely hear and smell better than it could see and relied on those two senses more than its own eyes (which, unlike T. rex's, were not forward-facing).

Triceratops: The three-horned tank

Typically portrayed as the yang to T. rex's yin, Triceratops is easily one of the most popular and instantly recognizable dinosaurs of all time. A quick look at this three-horned tank could easily show how this archetypal ceratopsian survived all the way to the end of the Cretaceous period.

People compare Triceratops to today's elephants and rhinos due to its size and stance. According to LiveScience, this 30-foot, 11,000-pound dinosaur stood on straight legs and possessed one of the largest heads of any land animal to ever exist. Above each eye was a long and pointy horn made of bone, which could have been used for stabbing and goring attackers. A third, smaller horn grew right above its nose. Meanwhile, its huge frill may have protected its neck or attracted potential mates. Triceratops' skull connected to the rest of its body via a ball-and-socket joint. According to experts, this one-of-a-kind adaptation allowed Triceratops to rotate its head nearly 360 degrees and deal with threats from any direction.

A 1996 analysis of Triceratops bones revealed tooth marks from T. rex, suggesting that it did try to make the horned plant-eater part of its diet. Other paleontologists found proof of Triceratops surviving T. rex attacks, thanks to bones that partially healed from T. rex bites. Sadly, the idea that it charged at opponents like a bulldozer. is likely untrue Nevertheless, its unique characteristics made Triceratops one of the most remarkable — and dangerous — herbivorous dinosaurs of its time.