Real-Life Scooby-Doo Mystery Villains

If Scooby-Doo taught us anything, it's that ghosts are usually nothing more than people trying to bamboozle other people for one reason or another. While that show's clearly fiction, there actually have been real people in history who pretended to be ghosts or monsters for financial gain, fame, or petty revenge.

Patch-Eye Pete and the haunted gold mine

Back in the days when gramophones were thing, a western mining company opened a gold mine in Korea. Unfortunately for the mining company — known as the Oriental Consolidated Mining Company (OCMC) — the local miners often stole gold and mining supplies. Many Koreans, at the time, were superstitious and believed in the supernatural, so the OCMC mine boss — a fellow with whimsical name of Patch-Eye Pete, devised a trick to stop the thieves. He plucked his glass eye straight out his head, placed it on a table near the exit, and told the miners that, through his eye, he could see if any of them were running off with stolen goods in the night.

This ridiculous plan actually worked for a while, until Patch-Eye Pete discovered the supplies were being stolen once again, and that someone had placed a cup over his glass eye to blind it. Luckily for ol' Patch-Eye, the Koreans also believed that each mountain had an ancestral guardian spirit that was to be respected, worshiped, and feared. So OCMC's next trick was to record a message on their gramophone — a new technology not widely known in Korea — pretending to be the voice of the mountain spirit, and to play it from the bottom of the mine. The ghostly voice echoing in the caverns warned that anyone who stole from the mountain would be punished. The next day, all the stolen goods were returned to the mine. Mama Patch-Eye must've been so proud.

The demon of Chateau Vauvert

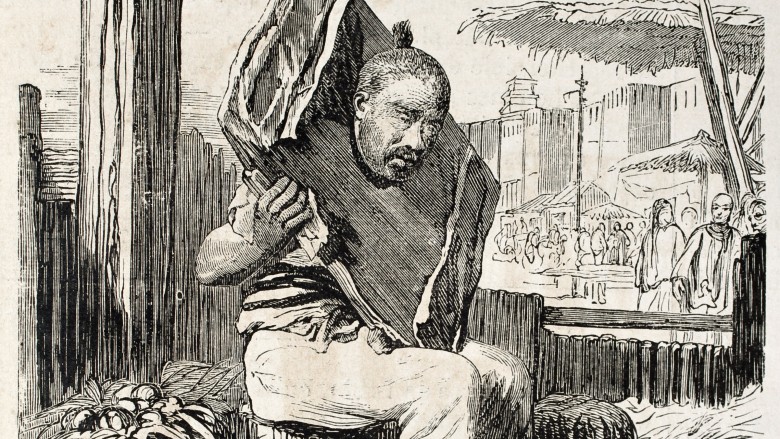

In the thirteenth century, in a place south of France known as Vauvert, there was a supposedly-haunted castle called Chateau Vauvert. Howling sounds and dragging chains echoed in the night, and people reported seeing strange lights and wisps in the windows. Worst of all, a fearsome green demon wandered the halls — half man and half serpent, with a long white beard, and a huge club that it used to threaten anyone who came near.

Skeptics believed a gang of criminals made their lair in the basement of Chateau Vauvert, and that they faked the haunting to scare people away. However, there were more likely perpetrators. See, the supernatural phenomena began as soon as a group of Carthusian monks moved into a small place next door. They later told the king that, if they could stay at Chateau Vauvert, they could exorcise the demons. The king believed them, and gave his permission for them to stay. As soon as the monks moved in, the hauntings conveniently stopped completely. The monks made Chateau Vauvert their permanent home.

So if you're searching for a new home, don't worry about mortgages or credit scores. Just say you'll get rid of the ghosts that are totally there. Boom, house is all yours.

The Hammersmith ghost murder case

In 1803, a ghost haunted a cemetery in the Hammersmith district of London — locals believed it was the spirit of a man who had committed suicide. It wore a white shroud and had big, glass-like eyes, which makes it sound like a Pac-Man ghost, or a marshmallow ghost you might find in a kids' breakfast cereal, but this ghost was anything but child's play. Rumors spread that an elderly woman and a pregnant woman both died of fright the night after encountering it. There were many non-lethal sightings too.

When a nightwatchman gave chase to the ghost, he witnessed it shed its shroud to run faster. After this, the locals became more brazen in hunting the specter down. A tax collector named Francis Smith took his loaded gun and went on aggressive, Zimmerman-esque patrols through the cemetery. One night he encountered Thomas Millwood, a 32-year-old plasterer, on his way to his parents home. As was customary for any plasterer, Millwood was dressed in all-white. When Smith saw Millwood, he shouted "Damn you. Who are you and what do you want? I'll shoot you if you don't speak." This was followed immediately by a gunshot, which struck Millwood's jaw with such force that it snapped his neck, instantly killing him.

Smith surrendered to the constables and was tried in court, where he was found guilty of murder, and sentenced to be hanged and dissected. But public opinion was not entirely against him and, after an appeal, his sentence was changed to probation, setting a famous precedent in English law.

As for the real Hammersmith ghost, he came forward shortly after Smith's arrest. Local shoemaker John Graham admitted that he'd been dressing up as the ghost to spook his apprentices, who had been scaring Graham's three children by telling them ghost stories. Graham was arrested and let out on bail. After that, there is no record of any punishment coming to him, so apparently it's pure anarchy when fake ghosts are involved.

Scratching Fanny

In 18th-century England, if a widowed man was to marry his wife's sister, it was considered incest by law. In 1760, William Kent did just that, eloping with his sister-in-law, Fanny Lynes, shortly after the death of his wife. Hoping to live in anonymity in the bustling city of London, they rented a room in a house on Cock Lane (stop snickering) that belonged to Richard Parsons and his young daughter. Parsons turned out to be a gambler and a drunken cad, who used his position to coerce Kent to lend him money, which Parsons seldom repaid.

However, Fanny became friends with Parson's daughter, Elizabeth, and the two would sometimes sleep together in the same bed. One night, while resting with Elizabeth, Fanny heard an eerie scratching noise, which she assumed was the ghost of her sister warning her about some imminent danger. William and Fanny quickly moved out of the house for good and, not long after, Fanny died of smallpox.

William sued Parsons for the money he owed him — coincidentally, the scratchings once again haunted Parsons' house. This time, Parsons claimed it was the ghost of Fanny, who would only scratch around Elizabeth, because of their close friendship. Parsons claimed that Fanny was trying to tell everyone it wasn't smallpox that killed her, but ratherWilliam, who had poisoned her with arsenic.

When the story spread throughout England, Cock Lane grew crowded with tourists hoping to hear "Scratching Fanny." Parsons, slick weasel that he was, set up a gift shop and began charging admission to his house. Even the famous politician Sir Horace Walpole paid a visit. Unfortunately for Parsons, all this fame brought the attention of skeptics — plus, William Kent really wanted to clear his name. When investigators interrogated Parsons, he went full George Costanza and doubled down on his lie, announcing that Fanny would reveal more by tapping on the lid of her coffin.

The investigators went to the cemetery alone, waited all night by Fanny's coffin, and heard ... nothing. The story was declared a hoax and, when investigators pressed harder, they found that Elizabeth had been making the noises, by scratching on a wooden board hidden in her corset. For Parsons' shenanigans, he was sentenced to two years' prison. Elizabeth, meanwhile, was let off on the grounds that she was merely obeying her father.

The ghostly drummer of Tedworth

In Tedworth, England in 1661, local landowner John Mompresson won a lawsuit against a gypsy drummer who had swindled him out of money. As a result, the court confiscated the gypsy's drum and handed it over to Mompresson. Soon after, the Mompresson family was haunted by strange drum beats, ghostly lights, and household objects moving on their own. It couldn't have been the gypsy drummer committing these pranks, because shortly after the lawsuit, he'd been deported for the crime of stealing two pigs. Therefore, the Mompressons believed that the gypsy had used witchcraft to summon a poltergeist to torment them.

The "poltergeist" drew national attention, and many visitors came to hear the phantom drumming for themselves. Strangely, the haunting stopped while Mrs Mompresson was in labor, and for a few weeks after the child was born, but resumed thereafter. The public opinion of the time was that it was all a hoax — a famous skeptic claimed that Mompresson's servants were punishing him for having sued the penniless gypsy. Another popular belief was that Mompresson didn't own his house and was actually renting it — he was using the manifestation to drive down the property value, thus decreasing his rent.

In any case, once tales of the ghostly drummer reached the ears of the king, he sent some men to investigate, and they concluded it was all a hoax. When Mompresson was summoned before the king, he admitted there was no ghost at his house ... although, once he returned home, he claimed again that the haunting was real. King's away, con-men will play

There is no record of anyone being punished, leading some to believe that perhaps the Mompresson children were doing it to tease their father. This is one case where the true villain remains unmasked.