The Wild Untold Truth Of Mountain Man James Beckwourth

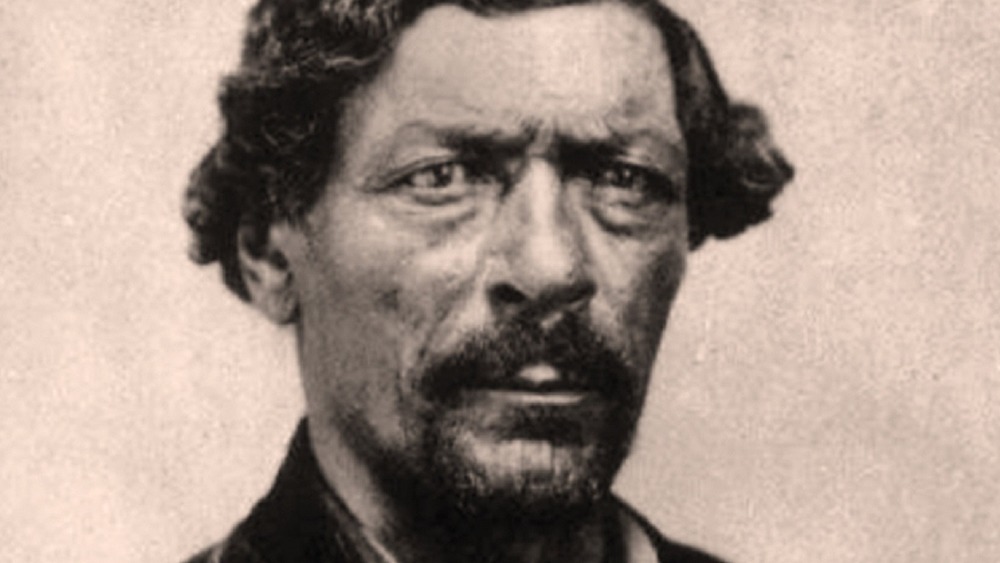

If ever there was a wild mountain man in the wilderness of the 1800's, it was James Pierson Beckwourth. Born into slavery, this enigmatic, notorious storyteller is memorable as one of the most colorful characters of the century. Although he often embellished his adventures, enough facts remain to herald Beckwourth as an important figure in the history of the West. And in a time when many African Americans were overlooked, Beckwourth was the exception. History Colorado verifies that during his lifetime, he was an explorer, fur trapper, guide, innkeeper, mountain man, scout, and avid storyteller.

Beckwourth has also been called an "author," stemming from his as-told-to biography which was penned by T.D. Bonner in 1856. But many, including American historian Bernard DeVoto, submitted that "Jim was a mountain man and the obligation to lie gloriously was upon him" (per the Salt Lake Tribune). Colorado State University also called him a "gaudy liar." Even so, while it is commonly known that Beckwourth spun more than his share of yarns, there is indeed a grain of truth to some of his many tales, as well as stories about him told by others. Read on for the crazy and wild life of James Beckwourth.

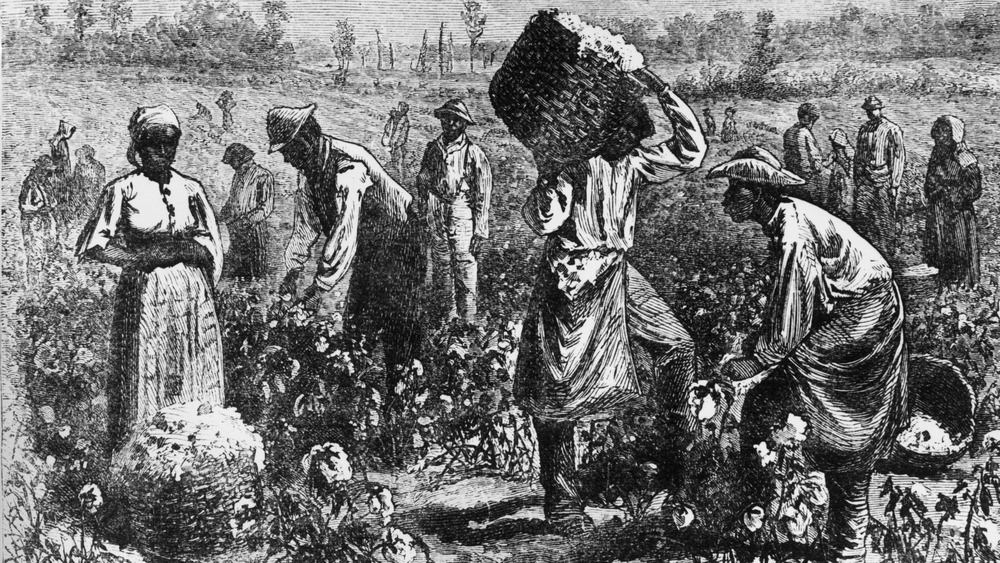

James Beckwourth's early life in Virginia

Nobody seems to know exactly when James Beckwourth was born. Some websites, like Encyclopedia, simply say he was born in Fredericksburg, Virginia circa 1800. Others, such as Colorado Virtual Library, claim he was born in 1805. Beckwourth himself said he was the third of 13 children and was born on April 26, 1798. What he does not mention, however, is that his mother was an African American slave who was actually owned by his Anglo father. According to the African American Registry, Beckwourth's father was Sir Jennings Beckwith (when and why James Beckwourth changed the spelling of his name is unknown). His mother, says Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, was a mixed-race woman identified only as "Miss Kill."

It seemed not to matter that Beckwourth was "born into slavery," since his parents reared him the same as any other family would raise their child—the exception being, according to America Comes Alive, that Beckwourth's father legally "owned" him. Beckwourth would recall that when the family moved to St. Louis, 22 slaves were taken along as well—and that soon after their arrival he found a group of his childhood friends who had been murdered by Natives. After attending school for four years and serving briefly as a blacksmith's apprentice, Beckwourth told his father he wanted to go west. True West magazine noted that Beckwourth's father filed a Deed of Emancipation with the court, officially granting his son freedom.

Beckwourth's life among Native Americans

Young James Beckwourth had good reason to resign the blacksmith trade: he claimed his employer physically attacked him. When he first headed west in 1822, according to Encyclopedia, Beckwourth joined Colonel Richard Johnson's expedition to the Mississippi River in hopes of negotiating a treaty with the Sac Indians for access to some lead mines. Beckwourth remained with the expedition for about a year and a half, working in the mines and learning the ways of both the Sac and Fox tribes. Then in 1824, Beckwourth spied an advertisement for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company looking for "One Hundred Enterprising Young Men...to ascend the river Missouri to its source," says America Comes Alive. Beckwourth answered the ad and was soon heading further west, buying horses from the Pawnees and honing his fur trapping skills, says Colorado Virtual Library.

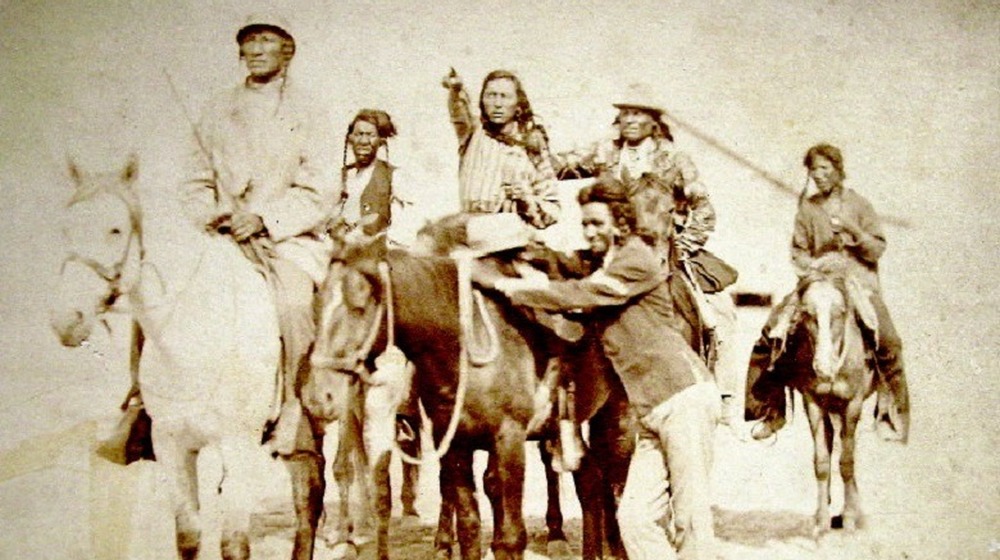

In 1825, reports True West, Beckwourth was in Wyoming when he attended the first mountain man rendezvous at Henry's Fork. At the second rendezvous a year later, a most interesting story was told by Caleb Greenwood, relates Black American History. Greenwood said Beckwourth was not mixed race but the Native American son of a Crow leader, and had been kidnapped as a baby. Those who saw Beckwourth's dark skin and knew that his manner of dress often included Native American garb naturally assumed the story was true.

Was James Beckwourth captured by Crow Indians?

Encyclopedia states that James Beckwourth spent some time with the Blackfoot in about 1827. There, according to Beckwourth himself, Blackfoot leader As-as-to offered his own daughter for marriage. But the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains claims Beckwourth actually fought the Blackfoot before being adopted into the Crow tribe circa 1828. At any rate, Beckwourth also said he was actually captured by the Crow before being "mistaken" (per an online Beckwourth biography) for the lost son of leader Big Bowl. As Beckwourth told it, he was taken to Big Bowl's lodge where someone remembered Caleb Greenwood's story and explained to the others, "That is the lost Crow, the great brave who has killed so many of our enemies. He is our brother."

Now welcomed as kin, Beckwourth settled in with the tribe and remained among the Crows for a dozen years, says America Comes Alive. During that time, Beckwourth learned even more about the Crow culture, as well as additional hunting and trapping skills. He also negotiated trade between the Crows and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. According to Colorado Virtual Library, Beckwourth married the daughter of one leader, eventually became a "war chief," and fought alongside the Crow against the Blackfoot. He would take "several" more wives before eventually leaving the tribe and returning to Missouri.

Beckwourth returns to the white man

According to America Comes Alive, James Beckwourth was only in Missouri for a short time before volunteering to fight the Second Seminole War. The trip to Florida was memorable; Beckwourth would recall that after partying with old friends in New Orleans, he boarded the Maid of New York and was seasick, after which the ship became stranded on a reef for nearly two weeks. He did eventually make it to Florida. American Black History says that although Beckwourth said he was a "soldier and courier" during the war, official documents show that he actually worked as a "civilian wagon master in the baggage division."

In 1838, Beckwourth left for Colorado. Encyclopedia verifies he was hired by Andrew Sublette of Fort Vasquez as a trader along the Arkansas River. Two years later he was at Bent's Fort (pictured), a noted trading center along the trail. Several sites, including Encyclopedia of the Great Plains and History Colorado, claim that Beckwourth founded today's Pueblo, Colorado. That's not exactly true: even Beckwourth himself acknowledged that he teamed with over a dozen other men to build "an adobe fort" that would become Fort Pueblo. And although Beckwourth arrived in Colorado with his wife, he married another woman as well. Her name was Maria Luisa Sandoval.

James Beckwourth, Luisa Sandoval, and John Brown

James Beckwourth may have indeed married Senorita Sandoval, but his time with her was short and besides, he identified her in his biography as Louise Sandeville. Their story goes like this: In about 1842, Beckwourth was at a place he called St. Fernandez in New Mexico when he married Sandoval and headed back to Colorado. Noted explorer John C. Fremont remembered seeing her at a camp along the Platte River shortly before the couple moved on to Pueblo (shown in this representation). The Greenhorn Valley View verifies the couple were living in Pueblo by October. The following spring, however, Beckwourth left Luisa and their daughter, Matilda, in Pueblo and took off for California.

Noted historian and author Janet LeCompte, who questioned whether Beckwourth really had anything to do with the founding of Pueblo, wrote that upon his return three years later, the frontiersman found that Luisa was now married to John Brown, a trader (and psychic!) at the settlement of Greenhorn some 25 miles south of Pueblo. Brown had shown Luisa a forged letter from Beckwourth claiming he no longer wanted her—or at least that is what Beckwourth claimed. He also said she tried to come back to him, but he spurned her. Beckwourth moved on; as for Luisa Brown, she moved to California with her husband, bore 10 children, and lived happily ever after. In 1897, her successful husband would pen The Mediumistic Experiences of John Brown about his time in the Rockies.

James Beckwourth and the California gold boom

James Beckwourth had already been to California once when he finally split with Luisa Sandoval Brown, and in 1843 he headed there again. Encyclopedia verifies that for the next several years, the man would ramble over the Southwest towards the Golden State, gambling, trading horses, working as a guide for the Army and arriving in Los Angeles in time to assist residents in their efforts to make California officially part of the United States. Beckwourth himself illuminated on his travels, talking of wrangling grizzly bears, dealing with Natives, mining, and discovering a pass that today remains named for him.

Located in the Sierra Nevadas, Beckwourth Pass lies at an elevation of 5,221 feet, says California's Office of Historic Preservation. Beckwourth's online biography submits that he "discovered" the pass during the spring of 1850. After working to improve the trail for about a year, he was able to begin leading wagon trains to Marysville some 125 miles away. T.D. Bonner, Beckwourth's official biographer, wrote that the pass "greatly facilitated emigrants in reaching California." Weary travelers often stopped at his place nearby, which Legends of America says consisted of a ranch and trading post. Sierra Nevada GeoTourism notes that Beckwourth established three other passes as well but only Beckwourth Pass was made an official historic landmark, in 1939.

Beckwourth's ranch became a settlement

Today, Beckwourth, California is a rural settlement named for James Beckwourth's ranch, trading post, and hotel (pictured before renovation), according to the National Park Service. Beckwourth would later explain that upon building his cabin, he "finally found myself transformed into a hotel-keeper and chief of a trading-post." After the first cabin burned shortly after it was built in 1852, Beckwourth built another home and accompanying outbuildings. At the time, Beckwourth's ranch was the only one between Beckwourth Pass and Salt Lake City. Weary emigrants were greeted with a refreshing spring, green grass for their stock, and a place to rest before moving on.

Beckwourth's ranch made an ideal hub for travelers in its time. The Diggings, which says Beckwourth is now a "census-designated place," has documented some 4,144 mines in the area and says the population still hovered around 432 in 2010. Encyclopedia confirmed that the house was still standing, but the nearby City of Portola believes the cabin is actually the third one built by Beckwourth. Still, the "V-notched" logs are a typical building design dating to Beckwourth's time in Virginia. The house is now a museum, and is located a mile or so from Beckwourth's namesake community. The Historical Marker Database cites a total of eight markers in the area commemorated to Beckwourth.

T.D. Bonner was a guest at James Beckwourth's ranch

James Beckwourth's colorful biography, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, was the most famous work journalist Thomas D. Bonner ever wrote. Spartacus Educational says that Bonner was actually a guest at Beckwourth's California home in 1852 when he began writing the book. Although he has been called "an impoverished justice of the peace" by writer Tom Augherton and an "alcoholic temperance-writer and con man" by book reviewer Kenneth Wiggins Porter, (in his own critique of Elinore Wilson's book, Jim Beckwourth Black Mountain Man, War Chief of the Crows, Trader, Trapper, Explorer, Frontiersman, Guide, Scout, Interpreter, Adventurer, and Gaudy Liar), Bonner's work was the only first-hand account of Beckwourth's long and colorful career.

There are, of course, those who would denounce the biography as so much effluvium washing down the pike. But Utah historian Jeffrey D. Nichols rightfully points out that the art of being a mountain man included a knack for storytelling, and that Beckwourth's story to Bonner was "an extension of that oral tradition." The work took four years to complete and was published by Harper and Brothers in 1856. The book, says Beckwourth's online biography, was successful enough to merit a second printing as well as translation into French. Notably, Bonner was said to have made off with the book's proceeds. Although historians initially dubbed Beckwourth an "immortal liar," the National Park Service says scholars now believe the book to be "generally accurate."

Beckwourth's return to Colorado

According to Biography, James Beckwourth stayed at his California ranch until November of 1858. By the following year he was back in Denver. "James Beckwourth, the celebrated mountaineer, and famous Crow Chief arrived in our city a few days since," reported the Rocky Mountain News in November 1859, "and we understand with the design of spending the winter." History verifies that Beckwourth worked briefly as a storekeeper, but by 1861 the Rocky Mountain News found him "living on a fine ranche [sic], three miles up the Platte [River]." Three years later he was still there when the Rocky Mountain News reported that one Bill Payne appeared and tried to physically force his wife to give him her wedding ring. After a scuffle, Beckwourth shot the man in self-defense.

That was not the end of Beckwourth's troubles. In the fall of 1864, writes Jeffrey D. Nichols, Colonel John Chivington commanded Beckwourth to guide for him in preparation for the notorious Sand Creek Massacre. In the ensuing battle, says Smithsonian, around 150 Cheyenne and Arapahoe children, elders, and women were mercilessly killed, their bodies mutilated for trophies by some of the troops as their village was burned. For Beckwourth, who had maintained a relationship with the Cheyenne for decades, it must have been devastating. Afterwards, the Cheyenne "refused to trade with him anymore." Two years later, Beckwourth left Colorado for good.

James Beckwourth's mysterious death

James Beckwourth's enigmatic life includes a puzzle over his death. Colorado Virtual Library explains that he wound up in Wyoming in 1866, where he was employed as a scout at both Fort Laramie and Fort Phil Kearny. Alternatively, Tom Augherton maintains that Beckwourth was hired to guide military troops from Fort Smith in Montana to a Crow settlement in Wyoming. That would perhaps explain why Findagrave claims that his "last adventure" happened that same year, "when he fought in the Cheyenne War." The details of that war remain a bit sketchy, but it gets weirder: while Jeffrey D. Nichols maintains Beckwourth "returned to his beloved Crow territory," others tell a different story.

Several writers have maintained that Beckwourth was just visiting when he died at a Crow village in Albany County, Wyoming on October 29, 1866. Author Chris Enss explains that he may have been poisoned after refusing to go to battle with the Natives. According to Pueblo Library, Beckwourth fell sick shortly after leaving Fort Smith and "commenced bleeding." He made it to the Crow village where he died and was placed "on a platform in a tree" per tradition. True Facts, however, claims that Rocky Mountain News publisher William Byers made that story up as a way to boost sales. However it really happened, Beckwourth's body remains at the Crow Indian Settlement Cemetery.

Does James Beckwourth have descendants?

In the great tallying up of James Beckwourth's many children, it is difficult to ascertain just who they, their mothers, and their descendants were. By Beckwourth's account he married Luisa Sandoval and five Native American women (including Pine Leaf, pictured), the first of whom he killed after she was disloyal to him. Also by his account, there were upwards of five children: Matilda, Little Jim, Baptiste, and perhaps two other boys. History only mentions two Crow wives and that Beckwourth "fathered several children." Legends of America references two Native wives, one "Hispanic" wife and one "African American" wife, plus "several children." And Sierra County History maintains that Beckwourth's last wife was Elizabeth Ledbetter, whose two children by Beckwourth "died young." Later, he chose to live with another Indian woman identified only as Sue, but left everything to Elizabeth in his will.

Surprisingly, little is known about Beckwourth's descendants. Findagrave remains the best resource online, listing two of his children: George W. Beckwith [sic], who was working as a mail carrier for the Uncompahgre Indian Agency in Colorado when he was kicked in the head by a horse and died on Christmas day in 1876, and Matilda Mary Beckwourth Brown, whose mother Luisa Sandoval took her to California after marrying John Brown. Matilda did marry, but her children either never married, never had children, or had children who died young. If Beckwourth indeed has descendants out there, they remain unknown to this day.

Remembering James Beckwourth

Beckwourth may have left no descendants, but he has left a legacy that has been remembered in recent years. Aside from the Jim Beckwourth Museum in California, the famed frontiersman has been remembered in other ways. Actor Carl Franklin portrayed him in the 1978-1979 miniseries Centennial, which focused on the dynamic history of Colorado. Perhaps that is what inspired the city of Pueblo to celebrate "Beckwourth Day" in 1978. La Cucaracha newspaper reported that a parade and "other activities" would be celebrating Beckwourth's part in founding Pueblo. And there was more.

In 1994, Arts and Culture verifies, the United States Postal Service featured Beckwourth on its "Legends of the West" commemorative postage stamp sheet alongside Jim Bridger, Chief Joseph, Kit Carson and other notable folks from the Old West. Two years later, in honor of Beckwourth bringing the first emigrant wagon train to Marysville, California, the town renamed a park in his honor, says Alchetron.

The festivities kicked off with the first annual "Beckwourth Frontier Days," which Beckwourth's online biography described as a big celebration featuring historical encampments with period characters, history exhibits, a fiddle and bluegrass jamboree, gold panning, wagon rides and more. Most importantly, Beckwourth's biography by T.D. Bonner remains in print as a unique testament of what it was like to be an African American man in the Wild West.