The Crazy True Story Of The Persian Princess

Ancient artifacts are our lifeline to the past. Watch any show about historical finds, lost treasures, or even antiques to see these objects that not only put us directly in touch with history, but also have their own unique stories of how they survived to the present day and were found, which is often completely by accident.

Most incredible of these finds are mummies. There are only so many of these well-preserved corpses that remain undiscovered, and each one can give us a wealth of information about the time and place where the decedent lived. So, when a newly discovered one turns up, it can instantly become a big deal.

This was the case in 2000, when a mummy and sarcophagus showed up on the black market, sparking an international argument, lots of confused archaeologists and historians, and a story so full of twists that if it was fiction it would be considered too unrealistic to publish.

It was all there on the video tape

In October of 2000, authorities in Pakistan were alerted to the existence of a video making its rounds through the criminal underground. The video showed brief glimpses of a mummy and sarcophagus, offering it up to black market collectors for an eye-watering $11 million, according to Science. Since mummies don't typically turn up on the black market these days, it's pretty difficult to say if that's a fair price or not.

But sales of this sort are actually illegal under Pakistani antiquities law, according to Archaeology. Like most other countries in the world, Pakistan doesn't let random citizens sell priceless historical artifacts to just anyone, and a mummy isn't your everyday find, either. Its authenticity needed to be verified, for one thing, and it needed to be assessed for its historical value, not just its monetary value. Make no mistake, though. Artifacts can be, and regularly are, put on display to attract tourists and researchers — they can definitely make some cash for a nation lucky enough to possess them.

For a smaller country that's not very well-known for big archaeological finds or extensive museum collections, a heretofore undiscovered mummy could kick-start its own branch of Pakistan's tourism industry. Pakistani law enforcement immediately set out to locate the video's creators and find out the real story behind this purported mummy.

Following the threads of the mystery mummy

Before long, authorities were able to track down the man who filmed the video tape. His name was Ali Akbar, and he said that he did not actually own the mummy. In fact, he claimed that he just filmed the video and distributed it out. Instead, he pointed police to Balochistan and its capital, a city called Quetta. There, they could find the man selling the mummy, according to Archaeology.

Balochistan is a province in the western part of Pakistan and shares a border with Iran to the west and Afghanistan to the north. Quetta is about an hour south from the Afghanistan border, and the largest city in the province. There, police sought a man named Wali Mohammed Reeki, a tribal leader who was the mummy's actual seller, according to the information they had received from Akbar.

Police found Reeki at his home and questioned him. He admitted that he was trying to sell the mummy and that he had it there on his property, saying that he received it from the man who found it, and they had agreed to split the profits from its sale. Authorities seized the mummy and, later, charged Akbar and Reeki with breaking Pakistani antiquity laws, according to Penn State University.

The mysterious mummy-finding man from Iran

Wali Mohammed Reeki said that the man who had given him the mummy was named Sharif Shah Bakhi, an Iranian who discovered the sarcophagus, and the mummy inside, shortly after an earthquake, according to Archaeology. Police were also able to find this man and spoke with him. Bakhi confirmed the story Reeki had told. He had found the sarcophagus sticking out of the ground after an earthquake and had claimed it for himself. This had been in a much smaller town, also in Balochistan, about three hours east of the Iranian border called Kharan.

Satisfied with Bakhi's story but intending to ask him more questions later, police arranged for the mummy to be moved from Reeki's house in Quetta to the Pakistani National Museum in Karachi.

They didn't know it at the time, but they had just let what would turn out to be a huge lead in a future case slip right through their fingers. When authorities tried to find Bakhi again later to ask more questions and, presumably, also charge him for breaking Pakistani antiquities laws, he was nowhere to be found, according to Trafficking Culture. He has never been located since. Law enforcement doesn't even know if Sharif Shah Bakhi was his real name.

Taking a closer look at the black market mummy

Scientists at Pakistan's National Museum set to work right away, inspecting the mummy and sarcophagus they had seized from Reeki. It wasn't long before they announced their initial findings. The mummy was 2,600 years old, and it wasn't just a nobody, according to Archaeology. The body belonged to a member of Persian royalty, a princess named Rhodugune, who was a previously lesser-known daughter of Xerxes I (himself better known as the tall, bald-headed antagonist from 300 these days, though saying that movie took liberties with the historical Xerxes I would be a major understatement).

This raised quite a stir in the world of antiquities, because while Ancient Egyptians were mummified regularly, Persians were not, according to Penn State University. The researchers raised several theories for why there might be a Persian mummy, chief amongst them that Rhodugune might have married an Egyptian and requested their burial custom. Another possibility was that she had been captured as a child and raised as a daughter by Xerxes, but was originally Egyptian by birth, and thus she was mummified as a way of honoring her roots.

Either way, Rhodugune's mummy was immediately a one-of-a-kind — a preserved member of Persian royalty from two and a half millennia ago, and the only remains of the Persian royal family ever located as well, according to Atlas Obscura. She was the find of a century.

The Princess of Persia

All of this was news to Iran, of course, and they'd know because Iran is the modern name for Persia. Rhodugune was the name of one of Xerxes' daughters, but not much was known about her, and no bodies of Persian royalty from that far back were known to still exist until Pakistan made their announcement. Because the mummy was Persian and was reportedly found near the Iranian border, Iran felt that they had a valid claim to the body, according to Archaeology.

Iran reached out to UNESCO, a part of the United Nations that's focused on education, culture, and science, to register their grievance against Pakistan, according to Archaeology. Pakistan, in turn, retorted that since the sarcophagus and mummy had been found within Pakistan's borders, the mummy rightfully belonged to them.

This led to a lot of arguing between the two countries with UNESCO in the middle trying to play the part of the referee. Naturally, this wasn't easy to rule on because, in all fairness, both countries made really good points. Throughout the entire saga of the Persian Princess, both Pakistan and Iran continued their public arguing back and forth. It's anyone's guess how the conflict would have turned out between the two nations if things didn't end up the way they did.

Afghanistan makes their own claim to the Persian Princess

Sharing a border with both countries, Afghanistan finally stepped in — not to settle the argument, but to add a new layer to the mess that was unfolding. This was still 2000, and the attacks on September 11, 2001 and the ensuing military efforts to remove them from power hadn't happened yet, so the Taliban still held control of most of Afghanistan.

The Taliban put out their own claim on the Persian Princess, saying that she had actually been found within Afghani borders, not Pakistan, and smuggled out of the country, and thus they also had a claim to the mummy (and the potential wealth that might come from it). Not only that, but a short time later, the Taliban announced that they had caught the smugglers, who had confessed to the heinous crime, according to Archaeology.

The thing is, no one actually believed them, not even a little. The Taliban didn't have a great reputation for trustworthiness even back then, as they were more like a militant extremist group than actual politicians. As the puzzle of the Persian Princess continued to reveal itself, it became increasingly obvious that the Taliban made the story up, and they stopped pursuing their claim on the mummy almost as quickly as they put it out there, then sat back and watched everything from afar.

The conflict over the Persian Princess intensifies

To recap, Iran (formerly Persia) wanted the Persian Princess because of her ancestry, but Pakistan held fast to their argument that she was found within their borders. Pakistan then came back with a new announcement. The mummy wasn't Persian at all, but Egyptian! They argued that Iran now had no claim over the body. However, Iran pointed out that in the time of Xerxes I, Egypt actually was part of his empire, thus still keeping them in the debate.

Not only that, but according to Iranian authorities, they had an Italian archaeologist study a photo of the mummy's breastplate from the images that Pakistan had released, and this archaeologist had translated the language on it, which confirmed that the mummy was of Persian origin, according to Archaeology.

There was just one problem with this claim. The Italian archaeologist was real, his name was Lorenzo Costantini, but he came forward to say that he had never really examined the Persian Princess. Iranian officials had sent him a copy of an image Pakistan had released. He took a look at it, but since the photo wasn't clear, all he could tell was that the breastplate did appear to say "Xerxes" on it. Costantini said that while he had looked at a largely illegible photo at Iran's request, he had in no way confirmed the mummy's authenticity.

The Persian Princess begins to unravel

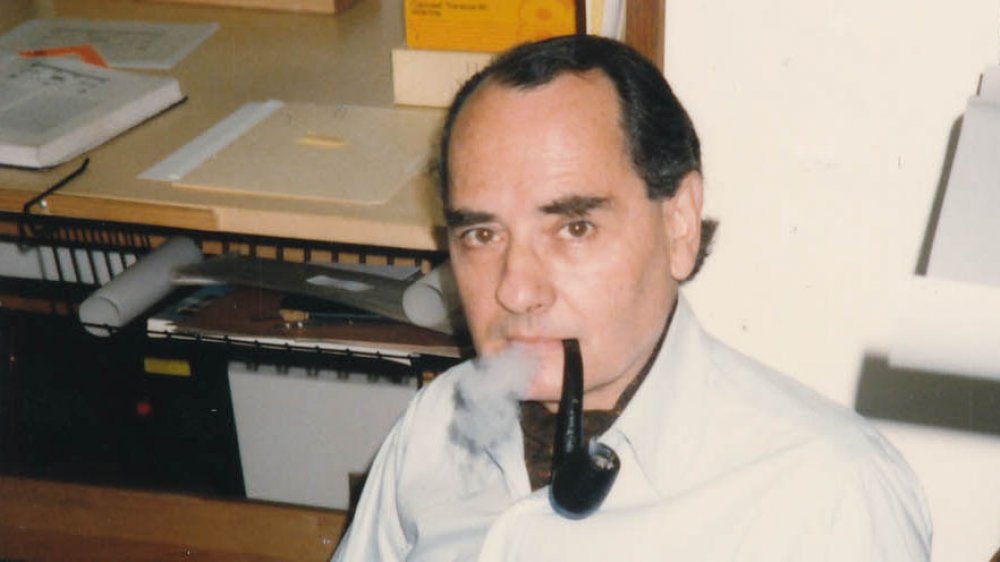

Meanwhile, during an interview with Archaeology magazine, an American archaeologist named Oscar White Muscarella was asked for his thoughts on the Persian Princess debacle. Muscarella wasn't familiar with the story, and when the interviewer explained it to him, Muscarella mentioned the story sounded awfully familiar, because he had been contacted by men trying to sell a mummy just a few months before, according to Archaeology.

Muscarella explained that he had been contacted by a man in New Jersey named Amanollah Riggi who was a representative for a Pakistani party who was interested in selling a mummy and wanted to know if he was interested, according to Trafficking Culture. As an archaeologist, Muscarella naturally said of course he would, even if he knew that it was likely to be an illegal sale.

He described receiving a video tape that sounded like an exact match of the one for which Pakistani police had arrested Ali Akbar. He had reservations but agreed to receive more detailed photos of the mummy and sarcophagus. But that wasn't all. Muscarella told Archaeology magazine staffers that he had declined to go any further with the sellers after determining that this supposed Persian Princess, which people were desperately arguing over on the other side of the globe, was a complete fake.

It took serious research to debunk the Persian Princess

Muscarella had requested the detailed photographs (later found to have been taken by Wali Mohammed Reeki himself) that Riggi offered. He looked them over, but immediately became suspicious when he saw the close-up photos of the mummy's breastplate, according to Archaeology. While Muscarella wasn't an expert on the old Persian language, he could see that there were several grammatical errors, and the entire second half of the inscription was actually plagiarized from an inscription credited to King Darius of Iran in around 520 B.C.E., according to Penn State University.

Muscarella reached out to a colleague more familiar with the inscription type and the form of the Persian language used in Xerxes I's time. He confirmed that the inscription was not proper Ancient Persian, and that the cuneiform lettering wasn't right at all. Not only was the language wrong, but it was definitely not an example of Ancient Persian inscription techniques or tools.

Based on the best estimations by Muscarella and the Persian expert, they were able to determine that the inscription was no older than the 1930s, max. In fact, they strongly suspected it was far more recent than that. Archaeology magazine, astonished by Muscarella's story, wrote everything up and published it in a subsequent issue.

The Persian Princess is exposed

Around the same time as the Archaeology magazine story hit newsstands (those were still a thing in 2000), Pakistan had finally allowed Iranian scientists to see their mummy in person. Those scientists announced that they, too, suspected the Persian Princess was a forgery, according to Archaeology. The wood inside the sarcophagus only dated to within 250 years, and there were pencil marks around the inscriptions, suggesting that they had been written out before being inscribed with a writing utensil ancient Persians didn't have. Within a few days, Pakistan finally admitted that they had been fooled. The mummy was a fake.

Suddenly, no one was all that interested in the Persian Princess anymore. She had gone from ancient royalty and the find of a century to a nobody within days. Iran and Pakistan cooled their feud, and the Taliban, who had just been proven to have made their whole story about smugglers up, whistled and walked away.

There was just one question left to answer. If the Persian Princess wasn't Rhodugune, daughter of Xerxes I, who was she? There was definitely a wrapped-up corpse stuck inside that sarcophagus, after all. Even if she wasn't royalty, maybe just the sarcophagus with the breastplate was fake. The mummy could still very well prove to be authentic, and thus might still hold some value, whether scientific or monetary.

Things turn very dark with the Persian Princess

After determining that the Persian Princess was a hoax, Iranian and Pakistani scientists took a look at what they could actually learn from the mummy, and what they learned was not all that pleasant. First of all, the body was a woman. She was aged somewhere between 20 and 25. All of her organs had been removed and her body filled with a powder that was determined to be a mixture of baking soda and salt, according to Atlas Obscura. This was further evidence that the mummy wasn't Egyptian — Egyptian burial practices required that the deceased's organs be removed only after embalming, according to Trafficking Culture.

In fact, as far as the scientists could tell, the Persian Princess wasn't even ancient. It seemed that this particular mummy had been made sometime in the 1990s, meaning it was less than a decade old, according to Archaeology.

Once they figured out the sarcophagus was fake, they had already assumed one of two possibilities. The body inside was either a random mummy someone found (keep in mind that mummies were once fairly common, as people used to grind them up and eat them as medicine, and this destruction of mummified bodies and other forms of mishandling actually made them rare) or it was a more recent body that someone had mummified to go with the fake sarcophagus. At least that part of the mystery was solved.

The last twist is the biggest one of all

Then there was the matter of how the Persian Princess died, and this is where things get extra weird. The scientists determined that she had died of blunt force trauma to the skull and spine. She wasn't just any ordinary mummy, according to Archaeology – she was a murder victim.

There are three main theories that have been suggested for where the body came from. The least horrible is that the body of a murder victim was stolen from its grave and turned into a mummy. Yeah, that's the least horrible. A worse possibility is that this whole thing was meant to cover up an unrelated murder someone had already committed. The worst possibility? That someone murdered this woman specifically so they could turn her into a mummy for their failed hoax.

Because of the body's condition after it was mummified, it was basically impossible for law enforcement to make any sort of easy identification. Police also sought out Sharif Shah Bakhi once again. He was probably their best chance at getting more information about the mummy's origins, but they were still unable to locate him. While Pakistani police opened a murder investigation, no one was ever arrested and the Persian Princess' true identify is still unknown as of 2020. One point of good news, though — she did receive a proper burial in 2008, according to the Pakistan Press Foundation.