Lies About Davy Crockett You Always Believed

The fragmented media landscape of today makes it nearly impossible for a craze to sweep the nation the way Davy Crockett swept America in the 1950s. Walt Disney's three-part serial for "Disneyland" was meant as a short but handsomely produced feature to help spotlight the Frontierland section of Disney's beloved theme park. But it struck a nerve with children and succeeded beyond all expectations. According to Randy Roberts and James S. Olson's "A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory," it never occurred to Disney that he was premature in killing off his latest hero at the Alamo. And the studio's marketing team was late in realizing the potential for merchandising and unprepared for the demand in coonskin caps that followed the show's premiere.

The Crockett craze of the 1950s proved as short-lived as it was intense. Historians were also quick to take Disney to task for the historical inaccuracies of his series — not that a Disney series with a catchy folk theme, folksy dialogue, and animated framing devices ever pretended to be an exercise in hardcore realism. Indeed, the heavily fictionalized show seems mild compared to some of the tall tales told about Davy Crockett in his own lifetime, sometimes by Crockett himself: That he was a half-horse, half-alligator who he could wade the Mississippi River, tangle with wildcats, and carry a steamboat on his back.

Those are just some of the tall tales told about Crockett. Many are more plausible than being part alligator and have entered into popular history accounts. But myths are myths, and here are some of the most pervasive about Crockett.

He technically wasn't born in Tennessee — or on a mountaintop

David Crocket — and he always referred to himself as David, not Davy — was born on August 17, 1786, near the town of Limestone. A state park now commemorates the spot, which is part of Tennessee, the region most associated with Crockett, even above Texas and the Alamo. The Volunteer State claims him as a native son and hero, and he served in the Tennessee General Assembly before representing one of its congressional districts. The Disney series theme song even began with the words: "Born on a mountaintop in Tennessee."

But the Crockett home, while relatively remote, wasn't on a mountaintop. And at the time he was born, the land his abode rested on wasn't part of Tennessee. Per William C. Davis' "Three Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret Travis," the Scots and Irish settlers who populated the region aimed to organize into a new state, Franklin.

In 1784, when the would-be state narrowly lost the vote necessary to receive statehood from Congress, its constituents broke away from North Carolina and became an independent republic. Crockett's father was a supporter of the Franklin movement, but it fizzled out before Crockett himself was old enough to understand any such activity. North Carolina reabsorbed the republic in 1789, and seven years later, the land became part of the state of Tennessee.

He wasn't an Indian fighter

The first episode of Disney's "Davy Crockett" was fully titled "Davy Crockett: Indian Fighter" and was loosely based around the Creek War, the clash between the Red Stick faction of the Creek Indians and the United States between 1813 and 1814. Disney presented Crockett as an active combatant who personally fought and bested the Red Stick leader before convincing him to make peace. In the John Wayne film "The Alamo," Crockett says fighting against Indian Americans was the only soldiering he ever did before coming to Texas. The real David Crockett took pride in being a veteran of the Creek War and used his service — sometimes wildly exaggerated — to his advantage when on the campaign trail later in life.

But Crockett was not an Indian fighter, in the Creek War or in any other conflict between white settlers and Native Americans. He was a first-rate hunter and scout by 1813, and his service as a volunteer was largely spent in those roles. By his own admission, he didn't think himself suited to warfare, and contemporary and historical assessments of his character paint a picture of a man too friendly to be a ferocious combatant.

Per "Three Roads to the Alamo," one of Crockett's few experiences with the real violence of war — which he recounted dispassionately afterward — was his participation in the massacre at Tallushatchee. During the clash, Creeks were shot down and burned in their huts in revenge for an attack on Fort Mims. To his own later disgust, Crockett and other desperately starving volunteers gorged themselves on recovered potatoes cooked in the grease that had dripped from the burned bodies of their enemies.

Crockett wanted to be a gentleman, not a ruffian

Texas Monthly once described David Crockett as "in essence, a nineteenth-century celebrity — perhaps the first American to make a living portraying his own fanciful image." Though essentially an honest man, he loved to entertain with boasts about his hunting expeditions, even before he entered the public eye. Once he became involved in politics, Crockett turned his natural charm and gregariousness to his advantage. Outgunned financially by his opponents, he told stories, cracked jokes, and on one occasion took the wind out of another candidate's sails by memorizing his stump speech and delivering it before he could.

Crockett's celebrity exploded nationwide by the time he reached the Capitol. People flocked to visit "Colonel" Crockett (colonel of a militia regiment being one of his first elected offices). His image as a buckskin-clad, semiliterate outdoorsman was lauded and lambasted by his respective allies and opponents. The zenith of Crockett's celebrity came when he was fictionalized as Nimrod Wildfire in "The Lion of the West," a wildly successful play that celebrated the frontiersman portrayal in heavily caricatured fashion.

The frontiersman attended the play's Washington benefit performance, and he continued to trade on his frontier image. But he was ambivalent, and at times resentful, at how much this caricature drove his reputation. It was Crockett's hope to be accepted as a gentleman, and he took care to dress and speak well when keeping company in Washington. Still, visitors were often disappointed on meeting him in his suit and cravat. Crockett later wrote his memoirs, partly to counter the Wildfire image.

He almost never wore a coonskin cap

The play "The Lion of the West," with its Nimrod Wildfire character, did much to amplify and shape popular legends about David Crockett. The illustration that graced the playbill, and the image of Crockett himself that appeared on "Davy Crockett's Almanac" (which he had nothing to do with) fixed his image in the public mind: a half-wild frontiersmen, dressed head to toe in buckskins, who went about wearing a fur cap. The initial illustrations showed a hat made of a wildcat pelt, but over time, the coonskin became fixed as the one and only Crockett cap.

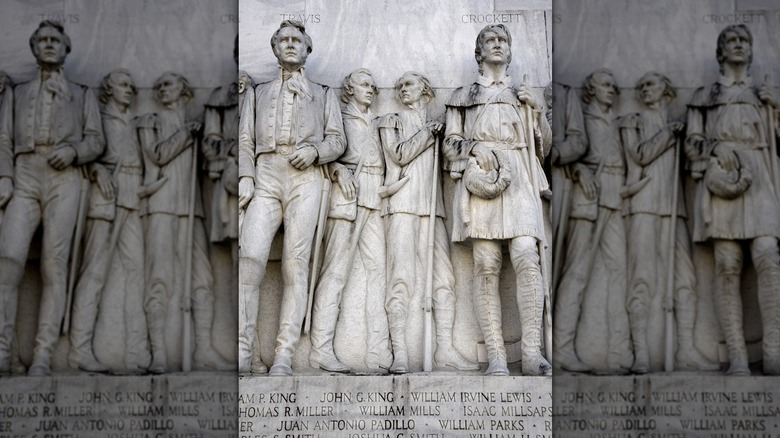

Hunting "coons" was part of Crockett's public persona. His political opponents castigated him as a "coon killer," an unserious buffoon. Crockett himself told tales of grinning racoons out of trees and turned an attempted insult to his advantage at a campaign event when he judged a coon pelt presented to him as no good. But there is no record of him ever having worn a fur hat of any kind before Nimrod Wildfire came along. When Crockett arranged for a portrait of himself in frontier garb (pictured), he posed, not with a coonskin cap, but with a popular felt hat with a wide brim.

Accounts of Crockett setting out for Texas or lying dead in the Alamo have him wearing the coonskin, or at least a distinctive hat. But these stories came well after his death. Assuming they weren't colored by the popular image of Crockett, they indicate that he only started wearing his trademark headgear at the very end of his life, in imitation of his fictionalized image.

His stance on the Indian Bill didn't end his political career

In the second episode of the Disney series, "Davy Crockett Goes to Congress," Crockett is depicted as losing his congressional seat — and any hopes for higher office — when he opposes Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Bill. It's an easy perception to have. Popular history accounts regularly give the Indian Bill issue prominent focus, often before anything else in Crockett's congressional career.

His opposition to Indian removal (which passed in 1830, per Texas Monthly) was real, and it was principled; he opposed the lack of congressional oversight of the funds granted Jackson, and he sympathized with the Native tribes who would be displaced (in contrast to the rest of the Tennessee delegation and virtually all of his own constituents). But the vote on Indian removal didn't represent either the high or low point of Crockett's time in politics. He did lose his seat in the 1830 referendum, but he was reelected two years later.

Reelection didn't bring any changes to Crockett's notoriously empty list of legislative accomplishments. But it did temporarily endear him to the leaders of the Whig Party, who courted Crockett as a potential presidential candidate for 1836. How seriously Crockett took a possible White House run isn't clear, but he was too independent-minded for the Whigs or any political party. When he lost his seat again in 1835, it seemed the end of his career. In response, he told his own constituents (via The Tennessee Magazine): "You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas."

Crockett went to Texas for votes, not violence

In a behind-the scenes-interview from the DVD of 2004's "The Alamo," Dennis Quaid spoke of his research for the film and quipped that "you didn't have people coming to Texas who weren't flawed people [in the early 1800s]. They came ... because they got kicked out of someplace else ... or they'd failed at something." So it was with David Crockett.Abandoned by his Whig allies after losing his congressional seat and hounded by supporters of Andrew Jackson, Crockett's political career seemed finished. In his personal life, he was estranged from his wife and her family. Texas, still a territory of Mexico open to American settlers, offered a fresh start. Old friends like Sam Houston had relocated there, opportunities for hunting and leisure abounded — and there was always the chance of a fresh start, personally and politically, if the move became permanent.

By the time Crockett set out for Texas, tensions between the Texians (both Anglo and Latino) and the central authority in Mexico were inflamed and well-known to Americans. But contrary to the 1960 "Alamo" film and other fictionalized accounts, Crockett didn't go with a mind for battle. When he arrived in January 1836, it appeared to many Texians that the fighting was over, or at least a far-off prospect. Crockett wrote back home that he was sure he'd be elected to help write a state constitution. It was only after he arrived, began playing to the crowds that greeted him, and caught the whiff of adventure in the air that he began claiming he meant to fight, declarations that were partly sincere heroism, partly canny politicking.

Crockett wasn't a commander at the Alamo

Popular accounts about the siege of the Alamo are full of myths, half-truths, and outright fiction, often filtered through contemporary politics and biases. One thing they generally get right is that command of the garrison was shared by William Barret Travis and Jim Bowie, at least until the latter fell sick. But in many popular accounts — Disney's TV series and John Wayne's "The Alamo" included — David Crockett is presented as a de facto third commander, present for all major decisions and deep in Travis and Bowie's confidence. Perhaps because of his fame, it seems irresistible, even inconceivable, to fiction writers that Crockett wouldn't be in the leadership of the garrison.

But Crockett was no officer, only a private, and he may not even have been leader of the so-called Tennessee Mounted Volunteers. Crockett originally came to Texas with three companions. When he enlisted with the militia and made for San Antonio, "Three Roads to the Alamo" has him down as the informal leader of a slightly larger group, but The Alamo Museum records William B. Harrison as the party's commander. Either way, Crockett was a famous and celebrated, but not empowered, presence in San Antonio when the Mexican army took the Texian garrison unawares and trapped them in the Alamo.

A counter-myth, presented in the 2004 film "The Alamo," portrays Crockett as insecure, somber, and lost within the Alamo's walls. But letters from Travis and survivor accounts shared by historians on the DVD's behind-the-scenes segment paint him as an energetic cheerleader and entertainer for the men, helping them to stay brave and dutiful.

We don't know how Davy Crockett died

There are two popular myths as to how David Crockett died during the Battle of the Alamo on March 6, 1836. One, popularized heavily in the mid-20th century, is that he went down fighting. Disney's initial miniseries on Crockett ended with him literally the last defender left in the Alamo, swinging his rifle like a club against an onslaught of Mexican soldiers. John Wayne's "The Alamo" had Crockett mortally wounded before destroying the garrison's supply of gunpowder, denying it to the enemy. This story has some support in the historical record. Survivors — including Susanna Dickinson, widow of Alamo defender Almaron Dickinson, and William Barret Travis's slave Joe — reportedly said they saw Crockett dead but surrounded by the men he'd slain.

But their accounts, per "Three Roads to the Alamo," were recorded from second-hand sources and were in any case told well after the fact, when trauma, pressure, and prejudice would have warped memories. And the "go down swinging" report of Crockett's death has competition from the "executed after capture" story. Taken from several sources, but largely from the diary of Mexican soldier José Enrique de la Peña, this account claims that Crockett and others were taken prisoner by a general who asked that they receive clemency. Instead, Antonio López de Santa Anna had them killed.

Per St. Mary's University, the authenticity of the diary is solid. But there are reasons to doubt de la Peña's identification of Crockett among the captured, not least because no such account was written down until much later. The only certainty about Crockett's death is that he died at the Alamo.