Lies About Hades And Persephone You Always Believed

Certain stories stand the test of time, if only because they speak to some present concern. This is especially true of the ancient Greek story of Hades and Persephone, which features a young girl abducted from her home and forced into marriage in a distant land — in this case, the land of the dead. Toss in some typical Olympian god machinations and inventive Greek reasoning related to the natural world, and you've got a tale that's lasted thousands of years.

But as is often the case with familiar information, much of what's repeated gets taken as fact without verification. Moderns also add shades of meaning to the tale of Hades and Persephone that folks believe come from the tale itself. Often, such misreading stems from grafting current-day narrative conventions and moral values onto ancient peoples, like wondering why Persephone has so little "agency," as a 21st-century graduate student might write.

This is especially true because stories like Hades' and Persephone's have been rewoven into numerous contemporary forms. Hades is often depicted as a cruel autocrat under whose thumb a rebellious Persephone chafes — a very modern-day take. But the truth is, happiness in marriage was not a prerequisite to the Greeks. The day-to-day substance of Hades' and Persephone's relationship — whether struggle-ridden, amicable, lovey-dovey, etc. — isn't discussed in the myth at all. It's more of a story about Demeter, Persephone's mother. In this way, the tale reflects broader Greek practices related to the absorption of wives into a husband's household but isn't representative of a typical marriage.

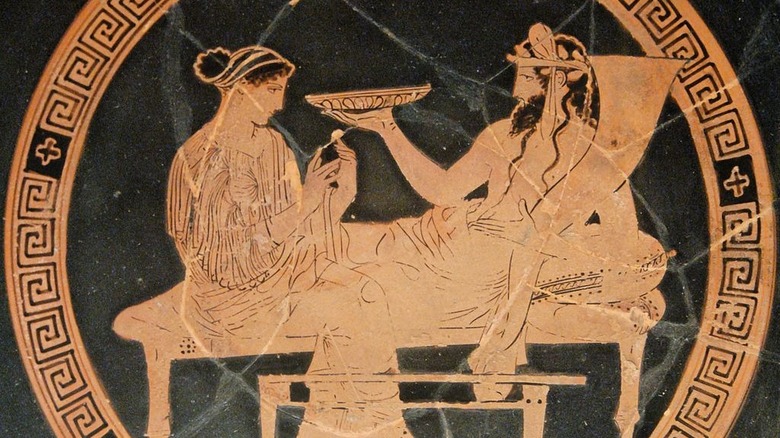

[Featured image by Alvesgaspar via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

The basic facts of the tale

At its heart, the story of Hades and Persephone explains the turning of the seasons. Seasonal reliability was absolutely critical to agricultural, subsistence societies like those of Hellas — the ancient name for modern-day Greece — which risked collapse with a single failed harvest. The natural world of the Hellenes was full of mercurial weather, natural disasters, plagues, death, decay, etc., but the greater yearly cycle remained stable — it still does. We move from spring to summer to autumn to winter, and that, at least, can be predicted. Why? It's all because Demeter, the Earth goddess, misses her daughter. Her sorrow yields autumn and winter, and her happiness yields spring and summer. Demeter is happy when her daughter, Persephone, comes home to visit.

We've got evidence for this tale going back to 1,500 B.C.E., well before it appeared in written form. Back then, Hellenes erected a stone temple to Demeter at Eleusis, which became a focal point for sacrifices to the goddess from that point forward. It was critical to keep Demeter happy because her moods determined the seasons.

In the tale, Hades saw the beauty of Demeter's daughter, Persephone, and took her back to the underworld to marry her. Demeter was furious, and caused a drought that forced Hades to release Persephone. But before he did, he gave her some pomegranate seeds to eat. These seeds bound Persephone to the land of the dead, and she could only visit the world above for a short time every year.

[Featured image by Yann Forget via Wikipedia | Cropped and scaled]

Lie: Hades and Persephone's marriage was typical

Sometimes, it isn't so much that people have been told a lie about Hades and Persephone, but rather people have made incorrect assumptions. The assumption in question happens often, namely, that folks believe writers of stories are tacit proponents of what happens in the story. In other words: Some believe that because the story of Hades and Persephone contains a kidnapping and forced marriage that the story advocates such actions. This couldn't be further from the truth.

In 8 C.E.'s "Metamorphoses," the Roman poet Ovid wrote his own reprisal of the Hades and Persephone tale where he described Persephone as "terrified" and "forced" (per Tufts University). Her mother Demeter was furious and "blamed all countries and cried out against their base ingratitude" before stripping away "the gift of corn." Typically, as The Collector outlines, ancient Hellenic families of would-be spouses formally agreed to a union. This doesn't happen in the story. Families also honored tradition via prescribed rituals. This didn't happen, either.

Some elements of the tale are true-to-life, though. There was a big age difference between Hades and Persephone, which is accurate (men married at about 30, and women 14 to 18). Persephone more or less "moved in with" Hades in his family home, which is also accurate. Ultimately, the story inverts ancient Greek values because Hades didn't show respect to Demeter and receive her formal consent to marry Persephone. This renders the story a cautionary moral tale about how to undergo a proper marital union.

[Featured image by Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 2.5]

Lie: A happy marriage was a requirement

Love and happiness in marriage are very modern ideas belonging to a society stable enough to entertain such notions. As The Collector explains, marriage in ancient Hellas was a contract amongst peer groups meant to strengthen community bonds. It was also a social event more than it was an individual one, and it was meant to produce children for the tribe, without whom there was no future. This is especially true for subsistence societies like those of Hellas, which was split up into nearly 2,000 small city-states. Happiness and love might have existed in certain marriages, but it was by no means a goal or even an eventuality.

And yet, time and again moderns misconstrue the story of Hades and Persephone by taking love and happiness as the chief concern of the tale, especially Persephone's. But much like we said before, this is a consequence of approaching another time and culture not within the framework of its own practices and beliefs, but contemporary conventions and values.

As the University of Oxford outlines, the concept of "love" in a romantic sense in stories didn't even exist until the 12th century C.E., originating with chivalric medieval values of fealty and loyalty (think knights rescuing damsels, here). Romantic love evolved through the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and modern era — buoyed by lots and lots of poetry. It came to mean sacrificing oneself to a single other person, which circled back around to marriage. This grand, centuries-long evolution happened millennia after the Hellenes lived and invented the story of Hades and Persephone.

Lie: Hades and Persephone are a hot, sexy couple

Strangely and even disturbingly, the story of Hades and Persephone has often been re-spun as a kind of hot, sexy paperback romance bordering on rape fantasy. Themes in this case revolve around suppressed sexuality, possession of another person, control, domination, and all such things that would tickle Sigmund Freud pink. Folks in multiple threads in multiple public forums have thankfully raised questions about this perspective. It should go beyond saying, but that kind of erotic take is not only patently untrue when looking at the tale's original text but speaks 100% of we moderns, not ancient people.

We can arguably trace the false erotic angle back to an extremely influential Bernini Gian Lorenzo marble sculpture circa 1621 to 1622 dubbed "The Rape of Persephone." At present, the sculpture and its title have nearly surpassed the influence of the original text, which was titled, "Homeric Hymn to Demeter," first written down in the late 7th to early 6th century B.C.E. The reader may recall that we said the story was actually about Demeter and her response to her daughter Persephone's abduction. But, even sites that specialize in Greek myth like Theoi refer to the tale as "The Rape of Persephone."

It stands to reason that the commonly believed, hot, sexy couple angle is a reflexive attempt on the part of moderns to cope with the unpleasantness of the original text's kidnapping. To do so, folks have redressed the power imbalance of Hades and Persephone into something more palatable to contemporary sensibilities.

[Featured image by Dosseman via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Lie: Persephone was too young to marry

Our final lie/misinterpretation stems from the same discomfort that moderns feel about what looks like, to us, a case of criminal abduction and child abuse. Namely, we're speaking of the age difference between Hades and Persephone. While both were immortal gods, Hades is usually conceived of as a solidly middle-aged man, while Persephone is envisioned as a young woman. But to the ancient Hellenes, a teenager wouldn't have been too young to get married — no Hellene would've batted an eyelash at this facet of the story. Once again, the point of the original tale was to demonstrate how Hades offended Demeter, the mother of his wife, by not following proper protocols and receiving a formal declaration of consent to marry. This was such an offensive move — especially between gods — that it changed the entire, natural order and created the cycle of the seasons.

While each Greek city-state had its own practices and customs regarding marriage, men generally married when they were older than women because of military obligations in their youth. Women, meanwhile, generally married as soon as they were capable of having children. As mentioned, having children was one of the primary functions of marriage because no children meant no future society. In fact, The Collector says that city-states viewed unmarried girls as a "'problematic demographic." And once a woman married and was adopted into her husband's household, dowry and all, part of the husband's role was to more or less raise her into adulthood.

[Featured image by Here via Wikipedia | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]