The Most Dangerous Assassins In History

In the wake of the attempted assassination of Donald Trump in 2024, many proclaimed it to be a definitive moment in the year's presidential campaign. But in the pages of The Atlantic, writer Derek Thompson pushed back on such predictions, writing: "The history of failed assassination attempts in the United States and abroad offers only the murkiest indication of the path forward." The men and women who tried to kill presidential candidates in the past did not sway their elections. By some interpretations of history, even successful assassinations — and there are few — have scant influence on the greater tides of history.

Nevertheless, from the murder of Alexander the Great's father in ancient Greece to the death of John F Kennedy in the 1960s, assassinations have brought down leaders in their prime, elevated dangerous and powerful figures, and scarred national characters. In the loss of popular, charismatic, and effective leaders, historians and laymen have seen prospects for a better world vanish, all on the whim of killers driven by delusion, power lust, or personal obsessions.

Nor is the danger of assassination limited to the immediate loss of one life. Through the carelessness of assassins unconcerned with collateral damage, some attacks have claimed scores of lives all at once, and the knock-on effects have helped trigger the unleashing of bedlam on nations, regions, and even the entire world. Here are some of the most dangerous assassins throughout history.

Bagoas the Eunuch brought down a dynasty

A peaceful transition under a hereditary monarchy requires an uncontested line of succession from ruler to child or, should there be no children, to the next blood kin. Disruption of such dynastic succession is an invitation to chaos. Infertility, accidents, and illness can all bring about such a break in a line, but at least one assassin in history allegedly sought to exterminate a dynasty, root and branch.

According to Diodorus of Sicily, Bagoas — vizier to the king of Persia – was a eunuch and without relations among the aristocracy and the court, which endeared him to his king, Artaxerxes III. In his rise to power, Bagoas provided invaluable help to Artaxerxes in his campaign against Egypt and may have helped to stabilize Judea. He is also alleged to have fattened his purse by selling the plunder of Egypt back to its priests. Rewarded with wealth, power, and trust by Artaxerxes, Bagoas repaid him with treachery. According to Diodorus, the eunuch poisoned not only the king, but every one of his sons except for Arses, who took the throne as Artaxerxes IV and functioned as Bagoas' puppet.

There is no reason given for Bagoas' treachery except a vague allusion to the cruelty of Artaxerxes III, and Diodorus' account of the entire line being murdered is challenged by other ancient sources. But it does appear that, after installing Arses, Bagoas faced a tumultuous kingdom which bore him no love, and he went on to kill Arses, too. Bagoas was executed by the next king, but the chaos he wrought left Persia vulnerable to Alexander the Great.

By killing Caesar, Brutus brought down the republic he sought to protect

The slaying of Julius Caesar by a group of Roman senators is perhaps the most infamous assassination of the ancient world. Caesar's military exploits had made him a hero of Rome, but his proud manner and rapidly increasing power unnerved conservative senators who wanted no kings above them. Many hands were raised against Caesar, but the conspiracy was lent credence by the participation of Marcus Junius Brutus, friend and protégé to the man he helped to kill.

If other conspirators were driven by jealousy, animosity, or ambition, Brutus was looked upon as a principled defender of the Roman Republic and a devoted Stoic. His ancestor was supposed to have helped expel the old Etruscan kings, a story Brutus took to heart. Whether he truly embodied Stoic virtues is another matter; for a man so offended by Caesar's pretensions of royalty and deification, Brutus was known for his own arrogance. And his betrayal was likely less of a blow to Caesar in his final moments than that of another coconspirator, Decimus.

Brutus does seem to have genuinely considered Caesar a threat to Rome as they knew it. But that Rome had been severely weakened by years of civil war, and Caesar's assassins did not expect the outrage from soldiers and citizens alike that would further destabilize the republic. Strife, purges, and the machinations of Caesar's grandnephew Octavian culminated in a new Roman monarchy — not a kingdom, but an empire. The powers of the Senate were curtailed and Brutus, defeated in battle and ideology, died by suicide.

The Hashshashin gave us the word assassin

It's commonly accepted that the English word "assassin" comes from the Hashshashin, also known as the Nizārī Ismāʿīliyyah or Order of Assassins. The origin of "Hashshashin" itself is obscure, though it's been suggested that it was a corruption of the Arabic for "hashish user," which was associated with the order. It may also have come from Egyptian Arabic, where "hashasheen" can translate as "troublemaker." And they certainly were troublemakers, albeit deadly ones.

Hashshashin were the followers of Ḥasan-e Ṣabbāḥ, father of a Shia sect based in ninth-century Persia. Ḥasan carved out a puritanical domain for himself before dying in A.D. 1124, and was such a zealot for his interpretation of religious law that he executed his own sons. The earliest Hashshashin maintained Ḥasan's authority through murder and espionage. They would ingratiate themselves to rulers and clerics opposed to him, learn their ways, and then kill without warning. For these killings, they were promised bliss in the afterlife, which they were sure to meet; many of these assassinations would leave the killer with no chance of escape.

After Ḥasan's death, the Hashashin continued to operate throughout Persia, Turkey, and Syria. Many of their targets were tied to the authority of the Abbasid caliphate, the Sunni rulers the Shia had long resented. The Hashashin resisted the Mongols and challenged the Turks in a campaign of assassinations and guerilla warfare, but by the mid-11th century, their strength was spent. Their last leader surrendered to the Mongols, who destroyed their strongholds.

The Sicarii fought Roman occupation with murder

The Hashshashin may have given us the word "assassin," but they weren't the world's first bunch of organized political killers. It's believed that the first group to engage in campaigns of assassination, espionage, and other acts we would now call terrorism was the Sicarii. "Sicarii" roughly translates as "dagger men" ("sica" refers to a curved dagger), which is how the Romans described the resistance group they faced in first-century Judea.

Jewish resistance to Roman rule, strongly motivated by their religion, was an ongoing issue for the Romans, but the Sicarii went beyond protesting for their faith. Beginning around A.D. 57, they killed soldiers and officials through quick and stealthy attacks, often avoiding capture. Their primary base of operations was Jerusalem, but they struck in surrounding villages. Rome was their chief target, but the Sicarii saw the shadow of Rome in Jewish priests and officials who they deemed collaborators, and they became victims of assassination as well. For money, the Sicarii sometimes kidnapped and ransomed collaborators or conducted violent raids on villages.

The Sicarii participated in the uprising of A.D. 66, near the height of their activities. They were part of the force that forced the Romans out of Jerusalem, but when the city was besieged in A.D. 70, the Sicarii were nowhere to be found. They were terrorists, not a disciplined army, and when cornered in Masada three years later, they opted for death by mass suicide rather than surrender. The revolt they'd helped to stir up ended with the expulsion of the Jews from their own kingdom.

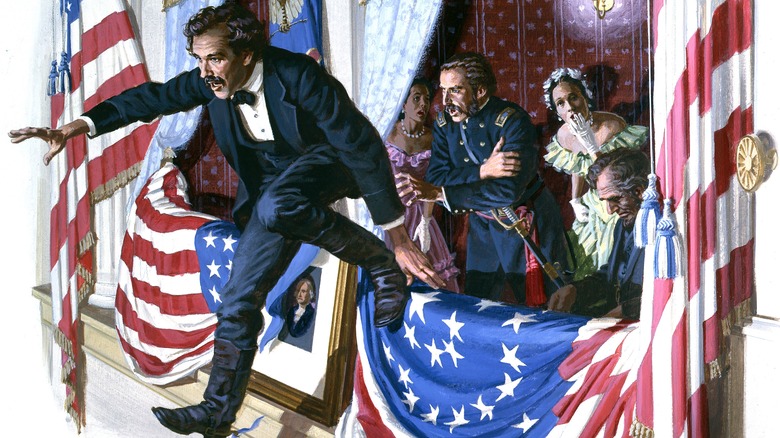

John Wilkes Booth likely worsened Reconstruction

John Wilkes Booth hadn't planned on becoming an assassin. He was a believer in the Confederate cause throughout the Civil War, despite being from a state that didn't secede and a family that supported the Union. To aid the Confederacy, he once schemed to kidnap President Abraham Lincoln and exchange him for Southern prisoners. When the South surrendered and Lincoln began to advocate for limited Black suffrage, Booth's thoughts turned to murder.

In killing Lincoln, Booth and his fellow conspirators hoped to spark a fresh wave of resistance among the Confederate states. Had he lived, he would have been disappointed; no new armies took to the field, the rebels were brought back into the Union, and American government continued under Andrew Johnson. But in a way, Booth's actions helped entrench many of the racist sentiments that drove the Civil War for generations to follow.

Lincoln's limited plans for Reconstruction after the Civil War were in some ways generous to the defeated Confederates, but he likely intended to push for suffrage, land rights, and opportunities for the newly freed slaves. To thread that needle would have been a tall order even for someone of Lincoln's political skills, and there's no guarantee he would have succeeded. But without him, an initial push for civil rights gave way to northern indifference, anti-Black forces regained and maintained power throughout the South, and groups like the Ku Klux Klan rose up to conduct campaigns of terror while legislatures planted the roots of segregation.

Indira Gandhi's assassination set off a massacre

The first prime minister of an independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru tried to unite its myriad religious and ethnic groups under one nation. His daughter, Indira Gandhi, remains the only female prime minister of India and has been widely celebrated for expanding social programs. But in her hands, the premiership disregarded parliament, manipulated judges and regional leaders, and both explicitly and implicitly condoned government corruption. Her time in office also saw a rise in tensions between Hindus and Sikhs, tensions Gandhi helped to exacerbate.

It was Gandhi who ordered Operation Blue Star, the violent expulsion of Sikh nationalists from the Golden Temple in Punjab that resulted in hundreds of casualties on both sides. And it was Operation Blue Star that was given as a motive when two assassins killed Gandhi on October 31, 1984. The killers were Gandhi's own bodyguards, both of them Sikhs who resented her role in the expulsion earlier that year. They shot her as she was walking to her office and followed her to death; one was killed after surrendering, and the other was executed.

The anger of Gandhi's killers was answered by a wave of anti-Sikh violence throughout India. Enraged Hindu mobs attacked Sikh homes and businesses. Some Sikhs were clubbed to death, some were brutally sexually assaulted, and others were set on fire. In many places, the mobs were aided and abetted by law enforcement. The scale and institutional support behind the violence was such that it has been labeled a genocide, and it claimed thousands of lives.

Rajiv Gandhi's assassin killed 14 people

Like his mother before him — Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi — Rajiv Gandhi joined the family business. Rajiv had his own career as a pilot and largely avoided politics in his younger days, but his politician brother's death triggered a change in ambitions. Rajiv stepped into his brother's vacant parliamentary seat and became a useful ally to his mother, Indira Gandhi. After her assassination in 1984, Rajiv succeeded her to the premiership, becoming the third member of the family to hold the office.

Rajiv was characterized as a reluctant leader, someone who listened and deliberated carefully. He was credited with economic liberation and a much-needed cleanup of government, ridding it of many of his mother's more corrupt subordinates, though he was attacked over some of his own appointees. In his first year, he also tried to moderate on the Sikh issue that had plagued his mother, but internal strife and scandal drove him from office in 1989. While on campaign to reclaim it in 1991, Rajiv's life echoed his mother's again when he was assassinated by a bomb in Tamil Nadu.

The killers were the Tamil Tigers, Sri Lankan militants with a long grudge against Rajiv for military actions in 1987. The bomb, hidden in a flower basket by assassin Kalaivani Rajaratnam – who died in the blast — killed at least 14 bystanders. A roll of film was recovered from one of the victims, a photographer. It showed Rajaratnam's approach to Rajiv and the initial flare of the blast that killed both subjects and the cameraman.

Gavrilo Princip started a world war

If any assassination has been credited with causing death and destruction far greater in scale than the initial act of violence, it's the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914. The act is commonly credited with launching World War I, although the truth is far more complex as tensions between the Great Powers of Europe had been rising for decades. Competition over imperial territories, tangled webs of military alliances, and festering hostilities in the Balkans were all driving the Old World toward conflict. But the assassination of the archduke was the domino that set the chain off.

The duke's killer, Gavrilo Princip, was not yet 20 years old when he committed his fateful crime. Perceptions of him and the organization he was a part of, Young Bosnia, have varied wildly by time and place. But the violence and espionage he was trained in certainly constitute terrorism, and he viewed an act of terror such as the murder of a major figure from the House of Habsburg as a pivotal step toward his dream of an independent and united Slavic state.

Youth saved Princip from the gallows after he murdered the duke. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison but died after just four, following amputation of his arm due to tuberculosis, and the war that Princip's actions had triggered was still waging when he died. However, with millions dead and treasuries emptied from World War I, the Slavic provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire merged with the Kingdom of Serbia to form the state of Yugoslavia, an independent Slavic nation as Princip had dreamed of.

The mafia's assassinations in Sicily helped cause their own downfall

Within the American Mafia, there's a longstanding rule that incorruptible public officials and law enforcement officers are off-limits to assassinations or violent reprisals. This policy doesn't come from any moral qualms but a practical one, in that the heat brought by such murders isn't worth it. But in Sicily, where mafia clans are smaller and less organized, violence among families and against the law is far more prevalent.

Though less cohesive than its American offshoot, the Sicilian mafia was a dangerous and parasitic powerhouse on the island throughout the 20th century. But in the 1980s and early '90s, there was a concerted effort to break the power of the mob, and one of its most charismatic and admired leaders was Giovanni Falcone, a magistrate who made it his mission to combat organized crime. He and fellow judge Paolo Borsellino pulled back the curtain on the mafia and its infiltration of society, and Falcone's Maxi Trial put over 400 mafiosi behind bars. In retaliation, the mafia killed him and his wife with a car bomb on May 23, 1992, along with three policemen.

In killing Falcone, the Sicilian mafiosi proved the wisdom of their American counterparts' prudence. The Italian nation was thrown into shock and outrage by the bombing; anti-mafia officials and activists took it as an act of war, and public anger intensified after Borsellino was killed the same year. New laws were written to combat organized crime and many of the mafiosi involved in the assassinations were brought to justice. The waves of mass arrests that followed have since crippled the power of the Sicilian mafia.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault or is struggling or in crisis, contact the relevant resources below:

-

The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

-

Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org