The Tragedy Of Theodore Roosevelt Explained

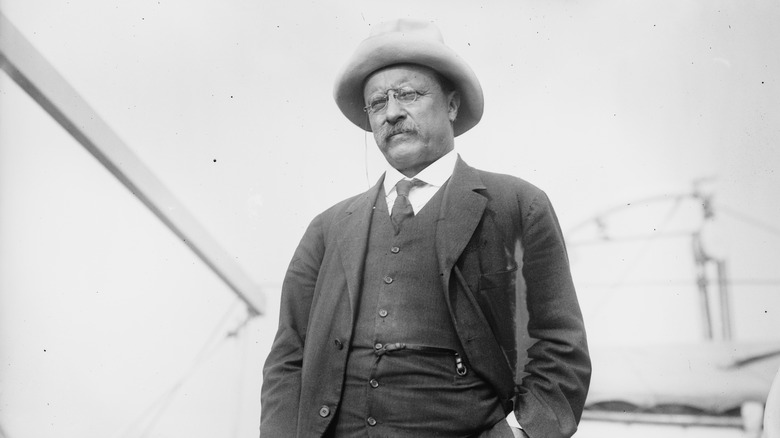

Nowadays, Theodore Roosevelt is something of a mythical figure. He idolized or just caricatured as a grinning, endlessly energetic man who can take a bullet and continue on with a speech, establish a national parks system, forge his way through both battle and dense rainforests, and generally stomp his way into American history with a cry of "bully!"

This isn't all wrong — Roosevelt had a frankly insane true story. He really was a conservationist who helped to establish many future U.S. National Parks and used the term bully pulpit to describe the influential status of a president — but neither is it totally correct. Teddy Roosevelt was a complicated man whose life and rise to power contained both dizzying highs and dramatic lows that shaped both the person and his legacy.

Things weren't always so bully for Teddy, even after he'd become the youngest-ever U.S. president at the fresh age of 42. From an early life that was marked by chronic illness amidst rare privilege to a young adulthood marked by two devastating family deaths, to very public political disappointments, to an ill-fated Amazon expedition that very nearly killed him, Roosevelt's tale clearly has its dark and tragic side.

Young Roosevelt was chronically ill

Born in 1858 in New York City, Theodore Roosevelt was already well-positioned in life. Young Teddy — or Teedie, as his family initially called him — was the son of a wealthy, long-established family. Yet, as he grew older, it became all too clear that the boy had fragile health. Young Theodore was undernourished and beset by frequent fevers and respiratory issues. Most infamously, he suffered from intense asthma attacks that left him terrified and struggling for breath. His parents sought medical attention, but many treatments of the day included potentially harmful practices like bloodletting, electric shocks, cigar smoke, and emetics meant to bring on vomiting.

Surely less damaging were the attempts to seek out fresh, open air, be that nighttime carriage rides in the city or more extended trips to Europe. And while confined to bed, Roosevelt was able to engage his mind, becoming a bookworm who consumed tales of heroic, masculine figures such as Ivanhoe and Robin Hood. Trips to the outdoors also appear to have engendered a love for wild spaces and the sciences, surely leading to his championing of what would become the U.S. National Park system.

As Roosevelt aged, his asthma seemed to fade into the background. Roosevelt himself said that his dedication to regular exercise was the key to his improved health (helped along via a home gym set up by his well-funded family). Yet he continued to deal with occasional asthma attacks as an adult during periods of intense stress.

Roosevelt's mother and wife died on the same day

As a young adult, Roosevelt began studying at Harvard in 1876, where he met Alice Hathaway Lee. The two married on October 27, 1880. By 1882, he was serving as a New York state legislator and, by 1883, the two were expecting their first child while planning an idyllic summer home on Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Alice gave birth to a daughter — also named Alice — on February 12, 1884. Teddy was away in the state capital of Albany, but rushed back to Manhattan when a February 13 telegram carried the news that Alice's health was rapidly deteriorating. When he finally made it home on February 14, Roosevelt found that his mother, Martha, had already died of typhoid fever in the same house in which Alice lay seriously ill. Mere hours later, while Roosevelt was by her side, Alice died of Bright's disease, an inflammation of the kidneys now more commonly called nephritis. Their daughter was only two days old.

Teddy shortly took to his diary, but only wrote that "The light has gone out of my life" and marked the page with a black X. A later entry recounted the union between Teddy and Alice, with Roosevelt writing "we spent three years of happiness greater and more unalloyed than I have ever known fall to the lot of others." On the next page, he wrote "For joy or for sorrow my life has now been lived out."

He fled from grief

Almost immediately after the deaths of his wife and mother, Roosevelt left for property he owned in the Dakota Territory, engaging in a kind of rancher's fantasy as he managed a cattle herd and went hunting. He had already been there a year before for an 1883 bison hunt, where he became enamored of the fresh air and energetic Western lifestyle. In 1884, after the New York state legislative session ended in the spring, Roosevelt traveled out to the Dakota Territory, establishing a second ranch and continuing his investments in the cattle industry there (he would also publish three books about his time as a Western rancher and big game hunter). At the same time, Roosevelt destroyed letters that mentioned the deceased Alice and ceased to speak of her for the rest of his life.

But, despite the deaths, Roosevelt left much behind in New York. There was a political career and property, to be certain, but also an infant daughter he'd left in the care of his sister. Young Alice grew to have a complicated relationship with her energetic and famous father. When he remarried to Edith Kermit Carow in 1886, Alice found herself competing for attention with Teddy's growing new family — a likely motivation for her hellraising behavior and oftentimes acerbic personality (which reportedly included earning a White House ban after she crafted a voodoo doll of first lady Helen Herron Taft and buried it in the front lawn of the residence).

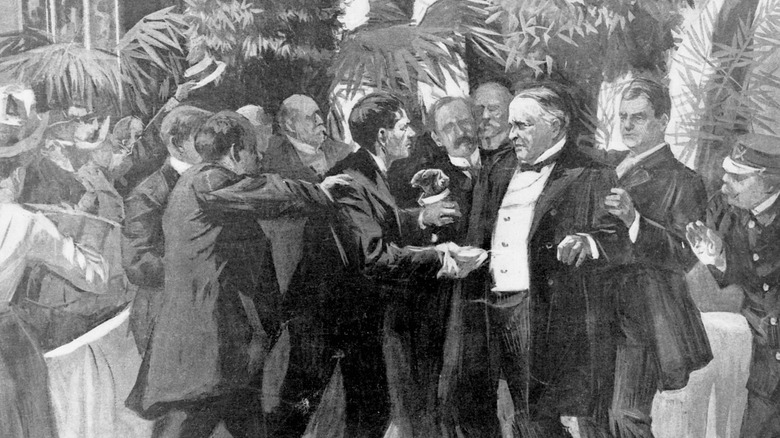

He became president due to a national tragedy

After his 1886 marriage to second wife Edith Carow, Roosevelt seemed to find new vigor for life, becoming the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, leaving that office to serve as a lieutenant colonel in the Spanish-American War, and gaining a masculine, heroic image for leading the Rough Riders cavalry regiment in the Battle of San Juan Hill. As a Republican, he then proceeded to win the election for Governor of New York in 1898. In 1901, he ascended even further up the political ladder, becoming vice president as part of William McKinley's administration.

Yet Roosevelt was hardly excited about the job. When McKinley was elected, he grumbled to a reporter, saying, "This election tonight means my political death" (via "The Roosevelts: An Intimate History"). He was pushed into the infamously powerless role by New York Republicans who had found the boisterous, reform-minded man troublesome. Yet party chairman Mark Hanna was still nervous. "Don't any of you realize there's only one life between that madman and the presidency?" he reportedly exclaimed (via Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural National Historic Site).

Mere months into the administration, Hanna was proven all too right. In September, an assassin shot McKinley while the president was attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. McKinley's abdominal wound became infected, and he died on September 14. Roosevelt suddenly became the nation's youngest-ever president at age 42. Roosevelt's subsequent term was successful enough that he won the 1904 election on his own.

Roosevelt may have had untreated mental health issues

If you asked political opponents of Roosevelt what they thought of the man's mental state, you would have surely gotten an earful. A 1912 profile in Current Literature, titled "A Scientific Vivisection of Mr. Roosevelt," paints a picture of Roosevelt — then campaigning for a third presidential term as a Progressive Party candidate — as a man beset by resentment and regret for leaving the White House. The result, at least according to some, was emotional instability and an untoward desire for more political power.

Of course, that could all be political posturing. However, a history of the Roosevelt family includes quite a few cases of apparent mental illness; Theodore's brother Elliot (father of future first lady Eleanor Roosevelt) dealt with substance abuse and may have died by suicide. Theodore's son, Kermit, was highly accomplished and productive, yet also experienced depression and alcohol abuse, and died by suicide (as did his own son, Dirck). Daughter Alice may have exhibited manic symptoms of bipolar disorder, while her daughter Paulina experienced depression and also died by an apparent suicide.

Was Theodore himself affected? A 2006 study published in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease suggested that, with his bouts of depression and periods of great activity and sociability, Roosevelt may have had bipolar disorder. However, it's important to note that this is still speculation and Roosevelt himself was never diagnosed with any such disorder during his lifetime, leaving the reality a mystery.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues or mental health, or is struggling or in crisis, contact the relevant resources below:

-

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

-

The Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

-

Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

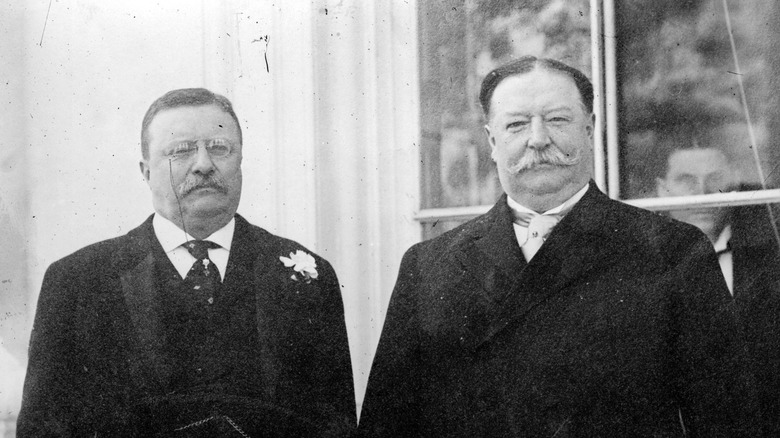

He bitterly and publicly argued with his protégé

By 1912, Roosevelt had served almost two full terms as president and had garnered a reputation as a progressive modernizer and U.S. expansionist. In 1906, while still president, he had even been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for shepherding a diplomatic end to the Russo-Japanese War (though, to modern eyes, his legacy is now deeply complicated by racist and imperialist views that informed many of his most lauded actions, such as seizing indigenous lands to turn into national parks).

But then there was the problem of William Howard Taft. Once a protégé of Roosevelt, by 1912 Taft had been elected president once and was running for another term as a Republican. Yet he ran on a platform that Roosevelt had deemed overly conservative and all too ready to work with corrupt politicians and undo his own trust-busting work. Taft responded by deeming Roosevelt a menace to the nation. An incensed Roosevelt ran as a third-party candidate for the Progressive Party, popularly known as the Bull Moose Party (and, no, you've got to stop believing the myth that he rode a literal moose).

Despite the painful and very public rift, things eventually simmered down. In 1922, Taft wrote to news editor George H. Lorimer that "I now cherish no ill will at all toward Theodore Roosevelt" (via The Gilder Lehrman Institute) — perhaps made easier by the fact that Roosevelt had died in 1919.

Being shot didn't help him win an election

When Teddy Roosevelt was shot in an attempted assassination, it wasn't the first time a president was nearly murdered. But it may be the first time in American history that the president then soldiered on with a scheduled appearance.

The incident happened the evening of October 14, 1912, during the fraught election year in which Roosevelt had resolved to run for president as a Progressive Party candidate against Republican William Taft and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. While on his way to give a speech, an assassin shot Roosevelt with a revolver. However, the bullet first struck Roosevelt's overcoat pocket, which contained a lengthy speech and his metal eyeglasses case. This slowed the projectile enough that, while it still entered Roosevelt's body, it did not kill him. He went ahead with his appearance, dramatically telling the audience that he had just been shot and the bullet was still inside him. He only went to the hospital once the speech concluded.

Though he played it off to his wife Edith as a mere flesh wound, the projectile had just stopped short of striking major organs. Doctors decided to leave it lodged next to a rib, perhaps remembering how an infected bullet wound had killed President McKinley (and led to Roosevelt's first term as president). But, though the incident shored up support for Roosevelt, it wasn't enough. With the Republican vote fractured between Taft and Roosevelt, Wilson won and became the next U.S. president.

He was plagued by arthritis

Though it's hardly on par with losing two close family members in a single day or being shot in a failed assassination attempt, Teddy Roosevelt's arthritis is far from a cheerful entry in his story. While the 1912 assassination attempt on his life had some obvious repercussions for Roosevelt — namely, the bullet that remained lodged inside his body, near his rib for the rest of his life — it also had an effect on his arthritis. Reportedly, the intensity of his injuries and the presence of that bullet exacerbated pre-existing arthritis, making his joints all the more uncomfortable for Roosevelt in the remaining years left to him.

Speaking to Today's Wound Clinic in 2018, Susan Sarna, the chief of cultural resources at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site (previously one of Roosevelt's residences), said that arthritis was an increasingly difficult problem for the president as he aged. The cause was perhaps rheumatoid arthritis, which caused painfully swollen joints that contributed to issues he experienced with walking. And, as a case report published in the Journal of Clinical Rheumatology noted, the two months before his 1919 death were preceded by fever and increased arthritic pain that struck the former president.

These may or may not have been familial, as his older sister Anna, more popularly called Bamie, dealt with serious attacks of arthritis throughout her adult life (the case report authors suggested that she may have had rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disorder).

An expedition to the Amazon irrevocably changed him

With the 1912 presidential election lost to Woodrow Wilson, Roosevelt found himself hanging around New York at loose ends. Then, he received a fateful letter inviting him to go on a speaking tour through South America. This appealed to the adventurous Roosevelt who one-upped the plan by tacking on a specimen-collection expedition on the Amazon River, bringing in a couple of naturalists from the American Museum of Natural History. Once there, he upped the ante again and decided that it was just the right time to attempt to map the Amazon tributary known rather ominously as the River of Doubt. Good thing Roosevelt's young adult son, Kermit, was already in Brazil and volunteered to join the group — in part because Roosevelt's wife Edith was worried that her aging husband was going to really overdo it this time.

Edith was right. Things started off well enough, with Roosevelt showcasing his classic energy and enthusiasm, but illness, insects, accidents, rushing waters, and supply issues plagued the dwindling group. As the weeks wore on, Roosevelt eventually grew seriously ill and endured an infected leg wound. At one point, he even demanded that Kermit leave him behind to perish.

Kermit sensibly refused and eventually Roosevelt rallied, finished the trip, and returned to New York in May 1914. Yet, the troublesome trip never quite left him, with Roosevelt finally retiring from the adventuring life and later blaming some of his medical issues on his Brazilian misadventure.

His son was killed in action during WWI

Born on November 19, 1897, Roosevelt's youngest son, Quentin, appeared to have inherited his father's extroverted charm and considerable energy. Much like Teddy and other members of the influential, moneyed Roosevelt family, Quentin also began attending Harvard at a young age. But, not long after his enrollment, the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917. Quentin quit college and joined the U.S. Army Air Service to become a combat pilot in Europe. There, he was shot down in the skies over France on July 14, 1918.

Four days later, Quentin's death was reported, though his family didn't get official word until July 20. For Theodore, who had been a vocal advocate for the U.S. joining the war and who encouraged his own sons to join up, this was an especially painful blow. Writing to French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau in July 1918, he claimed that "it is very bitter to me that I was not allowed to face the danger with my sons." He wrote to others that he was proud of his son's bravery and sacrifice, but admitted to daughter-in-law Belle Willard Roosevelt in August 1918 that "It is no use pretending that Quentin's death is not very terrible" and that Quentin's fiancee, Flora, might one day "keep Quentin only as a loving memory of her golden youth [...] As for Mother, her heart will ache for Quentin until she dies."

His death was a sudden shock

Though the 60-year-old Roosevelt was clearly aging by 1919, it still came as a shock to hear that the once vital man who gallivanted about the American West, led charges in battle with the Rough Riders in 1898, took the nation's highest political office by storm, and reportedly was considering yet another run for a third term, had died in his sleep. Yet, that was precisely the final tragedy in Roosevelt's life. The man who once wished to confront the mortal dangers of World War I alongside his sons had left the world quietly in the early morning hours of January 6, 1919.

His obituary published in The New York Times reported that his death shocked not only the nation, but Roosevelt's own doctors, who concluded that he was felled by a pulmonary embolism. The grim details of his death include that fact that he had suffered from inflammatory rheumatism, but while the painful condition hardly made his life easy, it didn't appear to have affected the blood clot that entered his lungs and killed him.

Though they had been political opponents, President Wilson officially announced Roosevelt's death the next day. "In his death the United States has lost one of its most distinguished and patriotic citizens, who had endeared himself to the people by his strenuous devotion to their interests and to the public interests of his country," Wilson wrote, then directed that all U.S. flags be flown at half-staff in Roosevelt's honor.