Rules People Had To Follow On The Oregon Trail

Many people dream of leaving their life behind and heading out on an adventure to seek fortune and a better standard of living. Such fantasies are nothing new. Indeed, this is what brought the first colonists to America in the 17th century. But once on the east coast, many settlers were still unsatisfied with their new living arrangements. The turn of the 19th century saw waves of explorers journey into the western frontier, a phenomenon which began to hit its peak in the 1840s and 1850s. Some traveled to escape disease outbreaks, religious persecution, or the Civil War, while others planned to hunt for gold or other assets on the West Coast. In 1862, Abraham Lincoln's government passed the Homestead Act, which stipulated that anyone willing to head West would be rewarded with free plots of land on which to settle, farm, and enrich themselves. The legislation prompted hundreds of thousands of people to take up the offer, and make the arduous journey on a route called the Oregon Trail.

The Oregon Trail cut from Missouri to Oregon, a distance of more than 2,000 miles that ran through the Rockies on the way to Fort Vancouver on the coast of the Pacific Ocean. But for those in the 19th century, such a journey represented an immense gamble, a travail of many months that meant incredible hardship and danger. Facing such a risk, pioneers were expected to follow certain rules to improve their chances of making it to their destination in one piece. Here's what it was like.

Organization and timing

The first concern for pioneers looking to conquer the Oregon Trail was forming a group — or "train" — that would travel the route together, sharing vehicles, drivers, tools, food, and medical supplies. By then, those preparing to make the journey would have sold off their homes, businesses, and anything they couldn't bring with them, and invested in supplies for the journey. However, some families chose to make the trek on their own after making preparations that could take years.

However a train was organized, it was vital that it set off from the East at the correct time of year. If the pioneers set off in the winter months, their carriages would become immobilized by snow and blizzards, while they would be at risk of succumbing to the cold. Many routes cut through high altitude mountain passes, where snow and ice remained for many months of the year. Travelers were obliged, therefore, to begin the journey in the spring, although that would mean facing intense heat and dust clouds during the summer months.

Obeying the constitution

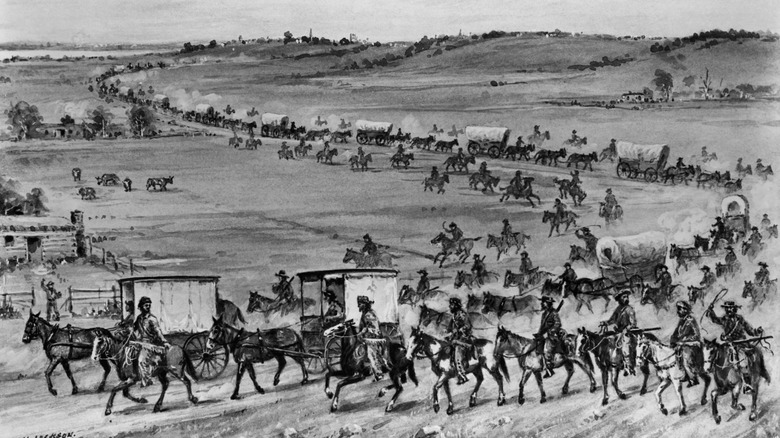

While smaller groups heading out on the Oregon Trail might form organically through friends and relatives, other larger trains were organized among strangers with a common goal. They included an average of 30 wagons and had up to 200, which together carried the luggage and supplies of hundreds of people, usually families. Occasionally, a group would total over a thousand people.

Such large numbers on such a dangerous route required management and expertise. For this reason, many wagon trains operated a hierarchy with appointed captains and officers. Travelers typically signed contracts with train organizers, which outlined the fees that they would pay upon their safe arrival. The group also typically agreed to abide by a written constitution, which imbued officers with the power to make decisions on the group's behalf, such as where to camp each night. There were other practical rules too, such as those stipulating the rotating order of the wagons to ensure that each party equally bore the brunt of the dust kicking into the air by the wheels of those at the front.

Pioneers agreed on laws of behavior before they set off

The contracts and constitution signed by travelers upon joining a wagon train typically included a system of laws tailored for that specific pack. Those containing religious groups, for example — such as missionaries or Mormons — would have the timing of religious services included in the travel contracts, and might have assurances of rest on Sundays.

The constitution of any individual wagon train might have included laws of behavior banning gambling or drinking, or rules regarding hunting and other activities that might help or hinder the traveling party. On top of this, the paperwork included frameworks for communal voting and decision-making, arbitration, and any form of justice that the group would adopt to overcome grievances between travelers or punish those who failed to follow the laws of the train. Those who erred egregiously could find themselves banished and forced to try and make it on their own. The code also outlined how pioneers were expected to act during an attack, and whether they would have to take up arms. For extra defense as they rested after a day's travel, they would align wagons into a circle or square to create a campsite and pen for livestock.

They had to pack light, or discard things on the way

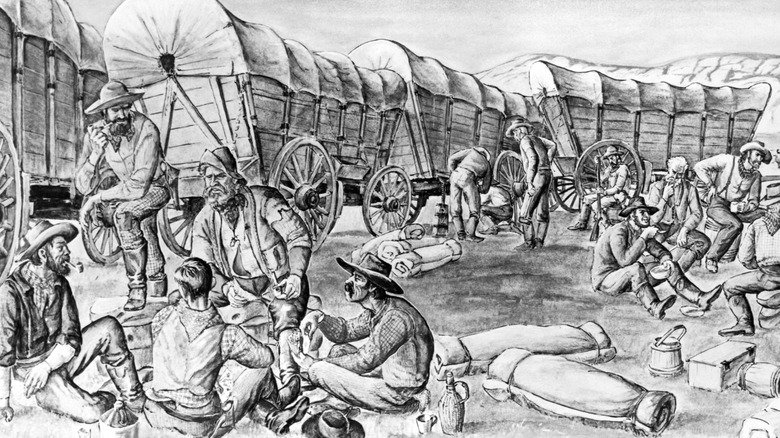

Journeying along the Oregon Trail back in the 1800s was far more arduous than it would be today. The rugged, barely distinguished paths wound through challenging, wild terrain. Most of those who made the journey did so with the use of wooden animal-drawn wagons called prairie schooners — mules and oxen were preferred, though horses were also used. The carriages were roughly 4 feet wide and 10 feet long, waterproofed with oil and covered by a cotton canvas. Equipped with unyielding wheels that had to traverse rough ground, the vehicles weighed around 1,300 pounds when empty, so it was a matter of great importance to make sure the load of each traveler was as light as possible.

Pioneers had to pack light, which meant making tough decisions about what beloved possessions to leave behind. Already forced to part with much of their property, those on the Oregon Trail were often required to lighten the schooners even more to account for difficult terrain or the loss of mules, meaning that the trail was littered with discarded objects. Instead of riding on the schooners and adding to the weight — the vehicles jolted violently in any case, making riding in them uncomfortable — able travelers tended to walk alongside them, covering around 16 miles a day on foot.

Disposing of the dead

More than 300,000 people set off on the Oregon Trail, taking their lives into their hands as they did. As well as the risk of exhaustion, malnutrition, and dehydration were they to run out of supplies or fail to find water in the searing heat, pioneers faced a barrage of other risks on their journey. Disease in particular took many lives and often decimated the populations of traveling trains. Smallbox, tick-borne diseases and scurvy all took their toll on those heading west, though cholera, which people caught primarily through drinking contaminated water, could kill within hours of being contracted, was the most feared and destructive illness of all. The danger was compounded by the risk of accidents and violence, although attacks by Native Americans were rare.

It is believed that up to 1 in 10 pioneers died on the Oregon Trail — a total of around 30,000 people, including many pregnant women and children. Because wood was a precious commodity on the route, those who died were often buried in articles of their own luggage or wrapped in blankets. Often, bodies were buried directly on the trail so that the wagons passing over the grave would impact the earth and prevent graverobbers and wild animals from digging them up. Where the dead couldn't be buried underground, their remains were covered in rocks.