Things You Should Know About Christopher Lee's War Record

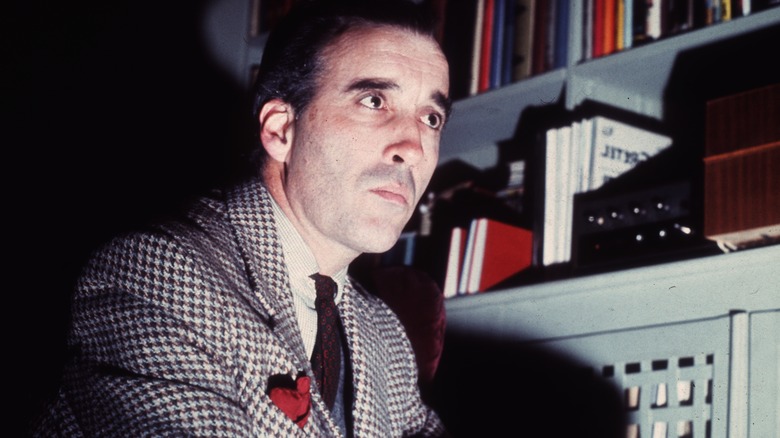

He was a Sith lord, a knight, a vampire, a wizard, a pirate, and a king — and that was just from his film resume. By the end of his life, Christopher Lee was a knight in truth, being made a Knight Bachelor in 2009. The honor was given largely for Lee's services to British drama — over a very long career, he set the record for having the most credited appearances by a living actor. He became famous for his work with Hammer Studios in their horror films, a distinction he wasn't always wholly pleased with. But fans who grew up with those horror films and became moviemakers in their own right gave Lee a late renaissance with featured parts in "Star Wars," "The Lord of the Rings," and the films of Tim Burton. And the legendary actor also carved out a late-in-life niche as a heavy metal singer.

But long before Lee was hailed for his contributions to cinema, often in the guise of villainy, he was a very real war hero. According to his memoir "Lord of Misrule," Lee was prepared to fight as early as 1939, when he and some fellow schoolboys dashed off to Finland to help fight the Russians. Their hosts patiently indulged these hot-headed and unneeded volunteers with uniforms and danger-free duty, and Lee soon went home, chastened by his uselessness. But in the thick of World War II, Lee enlisted with the Royal Air Force and worked his way up from warder to flight lieutenant over four eventful, dangerous years. And his service would be a major part of his story, in life and death.

His public account of his service was eventful and plausible

Christopher Lee devoted a fair amount of his memoirs to his wartime service, recounting hopes, fears, commendations, embarrassments, and close calls. He opened himself up to self-deprecation and frank confessions. When Lee first enlisted with the RAF, he hoped to become a pilot and thought himself a natural in early training. But just before he would have been cleared for his first solo flight, Lee suffered a debilitating headache and loss of vision in his left eye. The diagnosis was an unreliable optic nerve, and he was barred from flight. Elsewhere in the book, Lee admitted to being literally paralyzed with fear in moments of danger, including enemy fire.

But after failing as a pilot, Lee joined intelligence on his own initiative in 1941 and was praised by his superiors for such resolve. By 1943, he was attached to No. 260 Squadron during the North African campaign. In that capacity, Lee debriefed pilots, issued maps, ran interference with the squadron's companions from the army, and "broadly speaking, [was] expected to know everything" concerning intelligence, as he said in his memoir. He traveled with his squadron into Sicily, where he earned praise for halting a brewing mutiny via a lecture on Russia — after coming off one of his many bouts of malaria, no less.

Downtime had its own incidents, not all of them flattering. Lee admitted to getting caught in a brawl in an Egyptian club, "winning" when his opponent tripped over Lee's leg and knocked himself out. Absent from the memoir were any accounts of fantastical derring-do or espionage. It reads as a colorful, but eminently plausible, record of his service.

Lee wasn't a special forces agent (but he did work with them)

Absent from "Lord of Misrule" is any mention of Special Operations Executive (SOE), the reconnaissance and espionage organization also known as the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. And only a brief mention is made of the Special Air Service (SAS), a similarly storied commando unit. But part of Christopher Lee's legend is the widespread belief that he served with both groups during World War II.

Lee was never a commando or an SOE agent. But between 1943 and 1945, he was attached to both units several times as a liaison officer, as well as to Popski's Private Army. Liaison officers acted as vital connections between military branches like the RAF and special forces, helping to coordinate activities. In some cases, that meant traveling with special forces. In his memoir and in an interview, Lee said that he spent his last year of the war in Yugoslavia, which he told the interviewer was due to SOE operations.

In the later years of his life, Lee was asked more and more often about his involvement with special forces during the war. At times, he seemed to play coy with his answers. He once told The Telegraph, "Let's just say I was in Special Forces and leave it at that. People can read in to that what they like." In other interviews, he clarified his role in SOE. But he never gave details on operations. He sometimes blamed his tight lip on the Official Secrets Act, but he also seemed pained to remember some of his wartime experiences.

He was accussed of exaggerating his war record after his death

In a 2009 interview with The Times that touched on his war record, Christopher Lee was careful not to claim undue credit for any role he may have had in special operations. "Just because one was involved in certain operations, it looks as though you are saying 'I did it.' But really it's 'we,'" he said. And his public remarks on the war were always brief. But after his death in 2015, historian Gavin Mortimer took Lee to task for exaggerating his war record.

Writing for The Spectator, Mortimer pointed to certain interviews Lee gave late in life and complained, "Lee didn't exactly lie, but he did lead us on, encouraging us to believe [his liaison work] had involved more derring-do than it actually did." Mortimer dismissed Lee's claim of being bound by the Official Secrets Act, noting that SAS officers were allowed to write memoirs as early as 1948. Another historian, Guy Walters, was even more critical, accusing Lee in the Daily Mail of fabricating his early effort to fight in Finland's Winter War and even questioning his involvement with SOE, a part of Lee's service Mortimer accepted.

In his memoirs, Lee said that his final wartime service was with the Central Registry of War Criminals and Security Suspects (CROWCASS), arresting suspected Nazis. But CROWCASS, as Walters pointed out, was made up of desk workers compiling dossiers — they weren't out in the field hunting suspected war criminals. And there is no record of Lee in the lists of personnel in the War Crimes Unit, which did the fieldwork from CROWCASS's dossiers.

Lee may have talked up his war service in private

The posthumous charges against Christopher Lee of exaggerating his war record can seem unfounded when compared with his public comments. If he was sometimes vague or coy about his involvement with special forces, as Gavin Mortimer complained, he was forthright on other occasions. Guy Walters was suspicious of Lee's time in Finland and his alleged work with CROWCASS, but Lee never claimed to have done anything more in the Winter War than act like a cocksure youth. And his specific claim about CROWCASS was that he was seconded to an international effort to arrest those named by the agency's dossiers, not that he was a dashing Nazi hunter.

But Lee was known to evade or exaggerate the truth in less solemn areas of life than wartime service. He was one of those actors who wore a toupee but never admitted to needing it, for instance. And his account of his lightsaber battle with Yoda in "Star Wars" evolved over the years from a frank admission that he couldn't physically do much of the fighting, to saying he did "quite a lot of [it]," to, near the end of his life, saying it was all him.

He may have embellished his war record in the same way in private. Director Philippe Mora told Fangoria that Lee received a military welcome when they went to Prague for a film shoot, and that Lee claimed to have been involved in the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. But with such reports being uncorroborated secondhand accounts, there's no knowing what Lee said himself and what was embellished in the telling by Mora.

Fans and journalists exaggerated Lee's record more than he did

Christopher Lee may or may not have built up his war record among friends and colleagues, but his fans and the international press certainly did, in his lifetime and after it. Indeed, Gavin Mortimer seemed just as upset with some obituary writers as with Lee himself when he took to The Spectator. Specifically, The Independent claimed, without evidence or even a quote from Lee, that he'd personally been "behind enemy lines, destroying Luftwaffe aircraft and fields." Admiring peers from the movie business have mistakenly recalled him as being in the British secret service. And some publications even credited him with being the real-life inspiration for James Bond.

Lee was not the model for Bond. Ian Fleming drew on a number of different sources for the character, including himself. But Fleming did know Lee — they were step-cousins who often played golf together, among their favorite topics of conversation was Fleming's work. Lee told an interviewer once that every name used in the Bond books for a villain was a real name, and that he'd met some of the namesakes.

But despite truth and clarification being available in Lee's memoir and reputable news outlets, the embellishments on his record continue nearly a decade after his death. Articles and memes with exaggerations and half-truths still regularly circulate around the web.