What Happened To The Bodies Of The Apostles?

Given the importance of the Apostles — the 13 men (including Judas' replacement, St. Matthias) who formed Jesus Christ's inner circle and carried on his message — one might expect a solid record of what happened to them and their bodies, especially given the importance of relics and how carefully they are made in Catholic and Orthodox spirituality. Instead, the Bible is silent on the Apostles ' fate after death, leaving historians with oft-contradictory traditions and a handful of bones venerated across Europe and Asia.

As it stands now, most of the bodies of the Apostles — or the pieces left of them — are presumed to lie under the altars in a handful of Italian churches or the Vatican. History is not always clear how they got there and whether they are genuine — after all, forging relics was a favorite Medieval get-rich-quick scheme. Here is what Church tradition has to say about how the bodies ended up far from where the Apostles died, sometimes travelling across multiple continents to find their final resting place.

St. Peter

St. Peter, chief apostle and for Catholics, the first pope, is the easiest of the 12 Apostles to locate. His bones rest partially in the Vatican, and partially in Istanbul under the care of the Greek Orthodox Church. Early Christian tradition says Peter was crucified upside-down in Rome and placed in a tomb on Vatican Hill, which, according to an early Christian in the Roman Empire named Gaius, was fully visible from the nearby road. Almost three centuries after Peter's death, the Emperor Constantine encased the tomb in marble. Successive popes built over it thrice more — most recently, St. Peter's Basilica and Bernini's high altar.

Archaeological excavations in the 1940s and '50s lent more credence to the tradition. Vatican Hill did indeed host a large cemetery with hundreds of graves, including a marble-encased tomb containing the bones of a 60-70-year-old man. Inscribed on the tomb's walls was "Peter is here" or 'Peter in peace," depending on the reading.

Despite the potential bombshell, excavators numbered, boxed, and forgot about the bones. They were thrust back into the spotlight after scholars realized the marble tomb, the tradition of the Constantinian basilica, and the inscription all seemed to agree with the earliest accounts of Peter's tomb. The foot bones were even missing, possibly from having giant nails driven through them during an upside-down crucifixion.

St. James the Greater

Tradition places the body of St. James the Greater (otherwise known by the Spanish name of Santiago) in the Galician city of Santiago de Compostela in Spain – far away from his place of martyrdom in Jerusalem. According to Acts 12:2, King Herod Agrippa had James beheaded alongside the man who turned him in, both for professing Christ.

The rest of the apostle's journey relies on oral tradition. Before his execution, St. James reportedly preached in the Iberian peninsula. After his death, legend tells his body was brought to Iria Flavia in Galicia, either miraculously or by his disciples, and buried in the Libredón Wood with two of his followers. By the eighth century, this was a well-established local tradition, mentioned by saints such as the Anglo-Saxon cleric Bede and Asturian cleric Beato de Liébana. Armenian tradition, however, teaches that his head remained in Jerusalem, confusingly, in the crypt of the Cathedral of St. James the Lesser.

While tradition dictated the apostle's remains were in Galicia, no one knew exactly where, until a hermit named Pelayo claimed to have received a divine sign telling him the location of the tomb, where the incomplete skeletons of three people were found. Asturian king Alfonso II agreed and built a church there, which eventually evolved into the current Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela – the end of the famous Camino pilgrimage route. The bones lie under the cathedral's main altar for veneration.

St. Andrew

Most of St. Andrew's remains are held in the picturesque Italian seaside town of Amalfi, after a circuitous, multi-century journey from the Eastern Mediterranean. After Jesus' crucifixion, Andrew preached in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, most significantly founding the Patriarchate of Constantinople – the center of Greek Orthodoxy. For his work, he was crucified in the Greek city of Patras, where his followers buried him.

From Patras, Greek Orthodox tradition teaches that Emperor Constantius II re-buried Andrew in 357 – a sort of homecoming for the apostle to the church he founded. In 1204, however, internecine feuding between Catholicism and Orthodoxy moved them again. In one of the more messed up episodes of Catholic-Orthodox relations, the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, exhumed his remains, and took them to Amalfi along with some other deceased saints.

Before the body ever saw Italian soil, however, a handful of body parts reached Scotland, where St. Andrew enjoys the status of national patron. Tradition credits either St. Regulus or St. Acca of Hexham with bringing the relics, which in 1559 were destroyed at the hands of John Knox's Calvinist followers during the Scottish Reformation. Replaced in 1879 by a donation from Amalfi, they currently rest in St. Mary's Catholic Cathedral in Edinburgh.

St. Thomas

St. Thomas' body rests in many different places – a reflection of the apostle's long journey from Jerusalem, across the Indian Ocean and Central Asia, and eventually to martyrdom near the Indian city of Madras. Tradition says he was speared to death and buried under today's Catholic Cathedral Basilica of St. Thomas in Chennai, India.

The body's subsequent journey is recorded in various hymns and traditions. St. Ephrem the Syrian, writing in the fourth century A.D., attested the body's transfer to Edessa, writing in Hymn 42 of the Carmina Nisbena (via New Advent), "The Apostle whom I [Satan] slew in India is before me in Edessa: he is here wholly and also there." In the 12th century, after a series of attacks by Muslim Turks during the Crusades, the Crusaders transferred the relics from Edessa to the Greek island of Chios for safekeeping. Local tradition says that the apostle's skull is still there.

The remaining relics found their final resting place in 1258, when Italian commander Leone Acciaiuoli visited the tomb and saw a halo around the bones. So, he decided to transfer them to his native Ortona in Italy, along with the apostle's tombstone. This set of remains lies under the altar of the Cathedral of San Tommaso di Ortona, where they have survived natural disasters, a French siege, and a Turkish sack. In a final twist to the story, the Vatican sent part of St. Thomas' arm back to India, where it is housed in Azhikode's Marthoma Church.

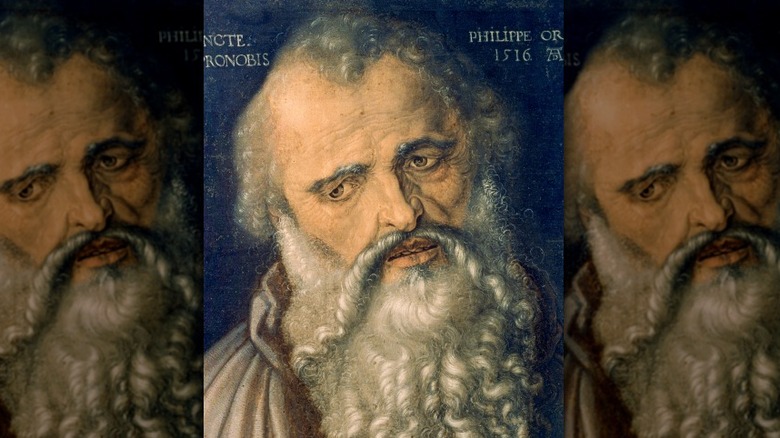

St. Philip

The remains of St. Philip are kept in Rome's Church of the Holy Apostles, their final resting place after a long journey from Turkey to Italy. Apocryphal (non-canonical scripture) accounts hold that the apostle was martyred in the Anatolian city of Hierapolis (modern Pamukkale, Turkey) for preaching Christianity by being crucified upside-down. The Acts of Philip say he was buried in the place he was killed, upon which a church was built several centuries later. Archaeologists digging in the ruins of Hierapolis have discovered a first-century A.D. tomb near the martyrium complex, which is believed to have been Philip's intended resting place, thus confirming at least part of the Acts narrative.

As the Eastern Roman Empire (aka the Byzantine Empire) suffered through crisis and foreign invasion, the apostle's remains were at some point removed to Constantinople. Under Emperor Justinian I, the general Narses and Pope Pelagius I built and dedicated the Church of St. Philip and James in Rome. The relics were sent there, and remain in the city's Church of the 12 Holy Apostles, the successor of the sixth-century original.

The Orthodox Monastery of Timios Stavros in Cyprus, however, claims part of the body remained in Constantinople until the 13th century, when it was taken to the village of Arsos — something Russian visitor Vasileos Barxy confirmed in 1735. Given the difficulty in tracing the provenance of medieval relics, it is impossible to determine which set of relics (or both) is the real thing.

St. Matthew

St. Matthew the Evangelist's purported body rests in the cathedral of the Italian city of Salerno, but no one knows how it got there. In fact, virtually nothing concrete is known about what the apostle was up to after Jesus' Resurrection and Ascension. After these two events, early Christian writers claimed he first preached among the Hebrews and then in a place called Ethiopia, a country near the Caspian Sea – not the African country. He was eventually martyred, but the details are scant. All the official Roman martyrology of the Catholic Church says is: "The birthday of St. Matthew, Apostle and Evangelist, who suffered martyrdom in Ethiopia, while engaged in preaching."

After his martyrdom, St. Matthew was likely buried. Given the Christian practice of burying martyrs in their places of death in order to encourage saintly devotions, one would assume he was buried somewhere near around the Caucasus. In the 11th century – and no one knows why or how – the saint's alleged body arrived in the Salerno. The city's Bishop Alfano had the body laid in a crypt, which pilgrims still come to venerate today.

St. Simon the Zealot

St. Simon the Zealot is a tough one to pin down. Purported relics of his body are found in Rome, the breakaway region of Abkhazia on the Black Sea, France, Germany, and Iraq, which matches up with just how many places he is alleged to have preached in.

Accounts of St. Simon's post-Ascension life place him everywhere from Britain to Iran, with just as many versions of his death. Some say he was crucified, Catholics believe he was sawed in half, while St. Basil the Great claimed he died peacefully in the Syrian city of Edessa. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church holds he was martyred in Samaria (North Israel). Several other traditions say he was martyred in Caucasian Iberia or a place called Suanir (probably in Colchis, modern Abkhazia), or the Lebanese city of Beirut. Given that he was martyred together with St. Jude, Beirut is considered the likeliest candidate.

Regardless of how he died, his purported remains somehow found their way to Rome, where they were laid to rest in St. Peter's Basilica, while a handful of other pieces of his body are scattered throughout. Most recently, the Novy Afon Monastery in Abkhazia received a single particle of the body encased in a medallion as a gift from Germany.

St. Jude

The body of St. Jude poses the same problem as St. Simon – namely conflicting traditions, placing his martyrdom anywhere from Armenia to Lebanon. One tradition has it that he was clubbed to death for preaching Christianity in Armenia. Ironically, the tradition of the Armenian Apostolic Church says he was martyred in Beirut instead. Whichever one is true, it is likely that he was buried where he was martyred, as was the practice at the time.

As with St. Simon, St. Jude's body found its way to Rome, although its journey is slightly better documented. The remains — today consisting of an arm – were reportedly taken from Beirut or Armenia under the Emperor Constantine around A.D. 333 and deposited in the old St. Peter's Basilica. When the current basilica was built, the relics were interred alongside the remains of St. Simon underneath the Altar of St. Joseph, where they remain today.

Judas Iscariot

The whereabouts of the body of Judas Iscariot, the man who betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, are unknown, and nothing attributed to him has ever been found. The precious little information about his body's fate comes from the Bible.

Matthew is the only Gospel to mention Judas' death, recounting that after his betrayal of Jesus, Judas felt so guilty that he tried to return the money to the priests. They refused it because it was blood money, so Judas died by suicide. Matthew is silent as to what happened to Judas' body afterward, but the Acts of the Apostles, written by St. Luke the Evangelist, offers some more lurid details. Acts says Judas bought a piece of land with the silver, but he took a tumble onto the field and split open, spilling his intestines.

As for Judas' final resting place, either it was buried where he died, known as the Field of Blood, in accordance with Jewish belief that a body should be buried as soon as possible after death, or it was left to nature. And that's about all there is on the remains of the only apostle not to be a saint.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

St. Bartholomew

St. Bartholomew's body today lies in the Italian city of Benevento's Basilica di San Bartolomeo Apostolo, having made a legendary journey from the Caucasus to the Central Mediterranean. After the Resurrection and Ascension, Bartholomew preached Christianity in the Caucasus. Upon reaching the then-Armenian city of Albanopolis (modern Baku, Azerbaijan), local pagans either beheaded him, or flayed him alive before crucifixion, depending on which version is followed. While his followers buried him there, the exact location is unknown, but the church built on the site of his death, which the Soviet authorities destroyed in 1936, would have been a good candidate.

After nearly five centuries in Albanopolis, the Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius transferred the remains to the fortress of Dura (modern Dara). But when the Zoroastrian Sasanian Persian Emperor Khosro I captured the city in 574, they were transferred out for safekeeping. Legend says Persian forces captured the chest of relics and dumped it into the Black Sea.

According to tradition, the body miraculously floated with the currents to the Italian island of Lipari. Local Bishop Agathon stored the relics in the island's church, where they remained until the mid-ninth century. As North African Muslims were poised to capture the island, they were moved to their current resting place in Benevento. Another handful of relics were transferred to Rome under Holy Roman Emperor Otto II, and are interred under the altar of the Church of San Bartolomeo all'Isola.

St. John the Evangelist

Brother of St. James the Greater and writer of the Fourth Gospel, St. John the Evangelist was the only apostle to die a peaceful death. Although early Christian writers, such as Clement of Alexandria, record that he was interred near the Greek Anatolian city of Ephesus around A.D. 100, and the site(s) of his tomb being well-known, the body's location is a mystery.

After his death, Christians disagreed which one of two sites was his actual burial. The place where Emperor Justinian eventually built the Basilica of St. John was recognized as the correct site, but legend has it that when Emperor Constantine attempted to recover the relics in the fourth century A.D., he found an empty tomb. Because of the lack of relics, some Christians believe his body was assumed into heaven, although this narrative had its share of detractors among early Christian theologians.

The only relic potentially attributable to St. John is a tiny sixth-century ampoule, containing ashes found near the Bulgarian city of Burgas. Archaeologists assumed it was picked up during a pilgrimage to the saint's tomb in Ephesus. It seems unlikely that it would be part of the apostle's body, however, since early Christians rejected cremation, so it might be some dust or ash taken from the tomb as a souvenir.

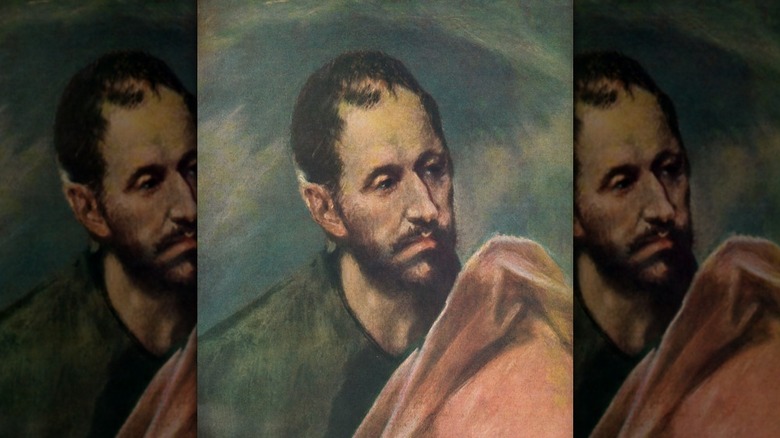

St. James the Lesser

Catholics have traditionally believed the relics of St. James the Lesser rest under the altar of the Basilica of the 12 Holy Apostles in Rome, having been brought there from Jerusalem. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church's martyrology "Mashafa Senkesar" recounts the Sanhedrin – the Jewish religious authorities – arrested the apostle and handed him over to the Romans, who then executed him. His disciples buried his body in a tomb under what is today the Armenian Apostolic Cathedral of St. James the Lesser, located in Jerusalem.

Around A.D. 572, the apostle's remains were brought to Constantinople and then quickly transferred to Rome under Pope Pelagius I and the Byzantine general Narses, so they might rest in the Basilica of St. Philip and James (the predecessor of the Basilica of the 12 Holy Apostles). However, a 2021 study published in Heritage Science concluded that the bone attributed to the apostle actually dates to the third century A.D., whereas one would expect a first-century date. If the dating is accurate, it means the location of the apostle's actual remains is still unknown.

St. Matthias

The location of the remains of St. Matthias — the apostle who replaced Judas — is disputed. Traditions agree he preached in Judea, Anatolia, and Ethiopia – in this case Colchis, around the Black Sea, rather than the African country. From there, a multiplicity of accounts agree he was executed in the Anatolian Greek city of Sebastopolis, but disagree on the method – either crucifixion, being speared to death, or chopped into pieces. An alternative tradition says he was stoned to death in Jerusalem.

These discrepancies make tracking the body down nearly impossible, since Christians disagree on his burial. St. Helena, mother of the Roman Emperor Constantine, believed he was buried in Jerusalem, as she transferred his relics from there westward. Those remains were split between Rome, Trier, and the Church of Santa Giustina in Padua. Catholic observers, however, noted she may have confused the apostle with St. Matthias, Bishop of Jerusalem – a man who lived years later, around A.D. 120.

If St. Helena confused the two men, and the relics in Europe do not belong to the apostle, there is the possibility they remained in Colchis. Fourth-century writer Sophronios says St. Matthias was buried in the Georgian fortress of Gonio-Apsaros. This tradition might make sense, considering the apostle preached there, but how his body got there (if it is there) is a mystery.