What New York's Danceteria Was Really Like

In the early 1980s, the New York City nightclub scene was doing the messy work of reinventing itself. Midtown Manhattan's Studio 54 closed its doors in February 1980 — the final blow that sent the disco era to its sparkly grave. Down in the Bowery, CBGB was ditching its new wave and radio-friendly punk roots in favor of faster, meaner hardcore sounds, and in Chelsea, the Roxy would soon evolve from a roller disco to a center of hip-hop and B-boy culture.

Out of this churning sea of death, rebirth, and cross-pollination rose Danceteria, a now-legendary nightclub whose history spanned 13 years and three New York City locations. If you're familiar with the club at all, you probably know it as an incubator for era-defining figures such as Madonna, the Beastie Boys, and pop artist Keith Haring. There was hedonism, of course — at one point, employees had to rig special sheets of lucite to keep cocaine out of the AV equipment — but there was also a strong sense of community and a commitment to artistic expression.

"I would call Danceteria a nation," DJ Mark Kamins told historian Tim Lawrence during a 2008 interview. "It was a new country, a new world, a special moment in time... Danceteria was one of those moments in history where everybody was at the same place at the right time, and everybody just fed off each other." From the dance floor to the rooftop, here's what awaited you during a night at Danceteria.

First Danceteria was innovative, jam-packed... and totally illegal

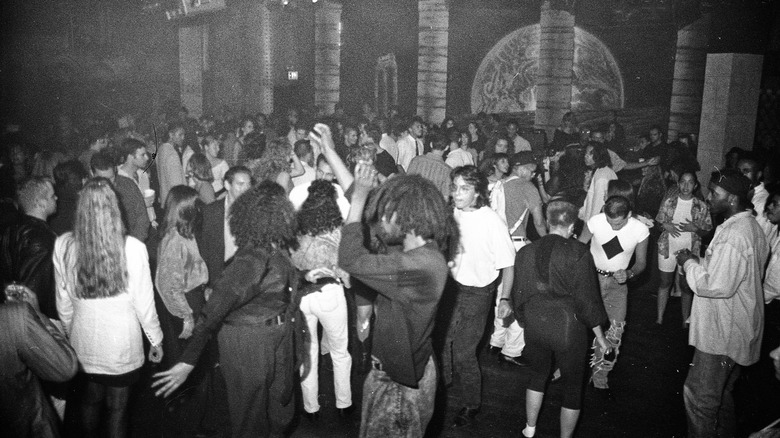

Danceteria opened on West 37th Street in May 1980; by June, it had enough club-scene cachet that the Rolling Stones hosted a party there (pictured) to promote their "Emotional Rescue" album.

The original, three-story Danceteria was unlike anything else on New York's club circuit. There were other venues that featured DJs, live bands, and video screenings, but none that offered all three at the same time. The walls were plastered with 1950s-style wallpaper and Xerox art by a young Keith Haring. There were intimate spaces with kitschy furniture and console TVs, and a basement dance floor where two DJs played simultaneous 12-hour sets. There was no air conditioning, but no one seemed to care. According to music culture historian Tim Lawrence's 2016 book "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983" (via Electronic Beats), 2,000 scenesters packed Danceteria every weekend night. New York's Daily News called the atmosphere "hard-edged, smoky, and menacing — in a cartoon sort of way." The club was, according to that outlet, "a punk version of Disneyland."

It was also completely illegal. The day after the paper published its glowing review of the club, it ran a short news item announcing that the venue had been raided by police and the State Liquor Authority for "allegedly selling liquor without a license." Thirty-five employees were arrested, 500 club-goers were "chased off the dance floor," and first Danceteria was no more. "Danceteria had absolutely no permits whatsoever," club co-founder Rudolph Piper remembered in Lawrence's book. "Then we got busted and said 'Okay, next!'"

Second Danceteria was essentially four (and sometimes five) clubs in one

Two years after first Danceteria was shut down for operating without licenses, the venue reopened in a former industrial space on West 21st Street. "Second Danceteria," as it's commonly known, lasted for four years and helped reshape American pop culture.

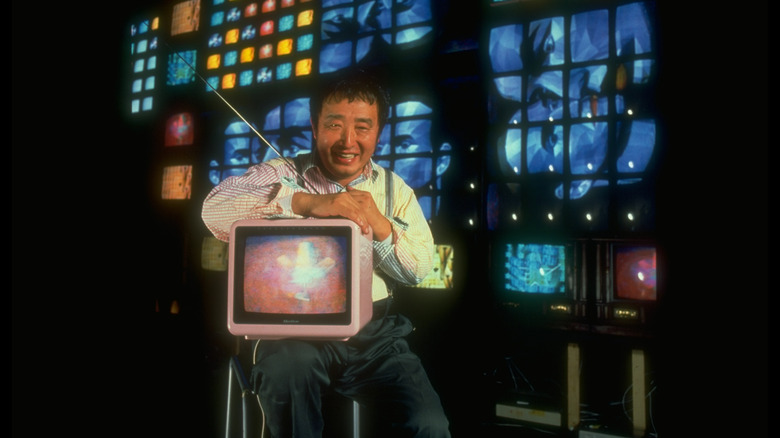

In 2018's "Beastie Boys Book," Adam Horovitz (above right) described second Danceteria as "the closest thing we had in Manhattan to an amusement park." Horovitz gave a detailed account of the club's layout: First there was the basement, where "weird stuff would go on" and the goth crowd tended to congregate, especially after Danceteria's management painted it black and started hosting "BatCave" goth nights there in 1983. The main floor hosted live bands, while now-legendary DJ Mark Kamins held court on the dance floor one flight up. The third level was devoted to a first-of-its-kind experimental video lounge where video artists Kit Fitzgerald and John Sanborn curated film and video pieces by David Lynch, Kenneth Anger, and groundbreaking video artist Nam June Paik. The vibe changed again on the fourth floor, which was devoted to a swanky, members-only club called Congo Bill, which mixed midcentury music with retrofuturistic décor. Finally, there was the rooftop, which, when the weather allowed, became an open-air party and dance space known as "Wuthering Heights."

"Danceteria was a mega structure, a utopia," Sonic Youth co-founder Kim Gordon told V Magazine in 2022. "There were many floors within the structure and each floor had a different feel to it, a different vibe."

You never knew what kind of music you'd hear next

Though it's closely associated with new wave, Danceteria's DJs and bookers curated a diverse lineup of dance music and live bands representing a wide range of genres. DJ Mark Kamins played an eclectic, ever-evolving blend of music during 12-hour sets at both the original Danceteria on 37th and the revival on 21st Street. At first Danceteria, Kamins shared turntable duties with British DJ Sean Cassette. The two had vastly different musical tastes, so patrons often found themselves dancing to punk one minute and funk the next.

"[W]hen they put me and Sean together at the first Danceteria, it was magical in a way," Kamins told "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor" author Tim Lawrence in 2008. "He would play [post-punk band Public Image Ltd] and I would go into a James Brown record, and it would work... I could play Donna Summer and Sean could play the Sex Pistols. It was all crazy. The book was open musically."

The club's bookers were similarly adventurous in their choices. Artists who performed live at the venue ranged from hardcore legends the Butthole Surfers to jazz-soul vocalist Sade Adu to avant-garde pianist and composer Philip Glass.

Music wasn't the only art form in the spotlight

In the 1980s, there was intense cross-pollination between the nightclub scene and the art gallery circuit, with clubs both vying to host the parties that followed gallery shows and openings, and curating exhibitions of their own. Gallery 98 compares '80s New York to Paris at the end of the 19th century, when cafes and dance halls of the bohemian Montmartre district helped shape the fin-de-siecle art movement.

So, while Danceteria was first and foremost a music club, music was far from the only artform that awaited club-goers on any given floor of the multilevel space. There was also a strong emphasis on visual arts, and on any given night you might've seen the work of some of the New York art scene's most vibrant creators. Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were recruited to paint murals on the walls (though Basquiat was promptly fired by club co-founder Rudolph Piper, who claimed his work on the job was "f****** terrible.") The venue regularly hosted fashion shows and exhibitions showcasing a wide range of visual and performance art, including paintings, photography, "light sculptures" projected from the rooftop, and more. Filmmakers such as Jim Jarmusch screened their work there, and up in the third-level video lounge, you might have caught early creations by video art pioneer Nam June Paik (pictured).

Drugs were literally everywhere

In an October 6, 1980, profile of Danceteria, the Daily News declared that "drugs are distinctly discouraged [in the club]" and pegged the venue's atmosphere as "somewhat wholesome."That take did not age well. Two days before the piece ran, when police raided the club for unlicensed liquor sales and arrested a gaggle of employees, liquor wasn't the only recreational substance on hand. "The dance floor was an inch deep in pills and glassine envelopes," remembers bartender Max Blagg, according to Tim Lawrence's "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor."

Things weren't any more "wholesome" upstairs. According to a Document Journal interview with video artists Pat Ivers and Emily Armstrong, the duo in charge of the original club's third-floor video lounge, Danceteria patrons snorted so much cocaine off the lounge's console television sets that the pair had to commission specially crafted sheets of acrylic to keep the powder out of their equipment.

The situation didn't seem to change much with second Danceteria. According to Stacy Gueraseva's 2011 book "Def Jam, Inc.," Def Jam Recordings founder Russell Simmons, who frequented the venue, would sometimes tip the bartenders with vials of cocaine.

The crowd was a melting pot of New York City scenesters

In the 1980s, New York City's nightclub scene was a patchwork of subcultures, with club-goers often segregating themselves according to their musical dispositions: punks at CBGB, B-boys at the Roxy, etc. When those clubs wound down for the night, their patrons made their way to Danceteria, where the party was just getting started. "The five floors of this supermarket of style were where gays, straights, artists, junkies, goths, skinheads, lost uptowners, sexy Jersey chicks, pinheads, Studio 54 leftovers, B&Ts ['bridge-and-tunnels,' or people from New York City's outer boroughs or suburbs], weirdos from outer space, drag queens, S&M freaks, hookers, performers of all sorts, East Villagers galore, not to mention musicians of all kinds, got together," Danceteria co-founder Rudolph Piper told Time Out in 2014.

"Danceteria was probably the first place where all people mixed," DJ Mark Kamins told author music culture historian Tim Lawrence in 2008. "It was gay, straight, Black, white, Latin, rock and rollers, disco, hip hop... It was the first cosmopolitan party where everybody came together."

You might have witnessed Madonna's first live solo performance

In 1982, Michigan-to-New York City transplant Madonna Ciccone was trying everything she could think of to break out of the New York club scene and into the mainstream spotlight. She had gigged around town in a couple of bands, drumming and singing for the Breakfast Club before fronting Emmy and the Emmys, but nothing stuck. She was reportedly so ambitious and competitive that some of her fellow club denizens held her at arm's length, but she found a willing partner — musically, professionally, and romantically — in music producer and Dancerteria DJ Mark Kamins. After the two started dating, Madonna convinced Kamins to play a demo of her first solo single, "Everybody," at Danceteria. The crowd responded fairly well, and Kamins, who was also working for Island Records at the time, took it to label honcho Chris Blackwell. Blackwell was unimpressed, so Kamins' next stop in his Madonna promo tour was Seymour Stein of Sire Records. According to an interview with Kamins conducted by author and historian Tim Lawrence, Stein didn't like Madonna's music either, but he trusted Kamins and signed her anyway.

With a record deal finally in hand, Madonna's next task was to impress her new label. Again she turned to Danceteria, this time recruiting doorman Haoui Montaug to her cause. Montaug curated a cabaret show called "No Entiendes," and it was he who first put Madonna on stage as a solo artist. She made her debut at Danceteria on December 16, 1982, for an audience of 300.

If you were a single dude, good luck getting in

At Danceteria, the doorman was royalty. After all, it was he who decided whether you'd be ushered inside to mingle with celebrities, or spend your evening waiting in line. Danceteria's door staff, often led by legendary New York City doorman Haoui Montaug, had a controversial mandate: Women and gay men were often welcomed inside, while men who weren't accompanied by either were made to wait in line. Danceteria co-founder Jim Fouratt (pictured), who had instituted a similar policy during his management tenure at Hurrah, hoped it would weed out men who became impatient or aggressive when they weren't promptly admitted. He credited the policy with keeping Danceteria relatively trouble-free.

"With my door people ... gay boys and women got in without any hassle," Fouratt told Paper in 2017. "With straight guys, the test was they'd have to wait a few minutes and see if they didn't get hostile. We never had a rape or a fight, or any of those kinds of things that happened in those kinds of clubs."

Not everyone appreciated the policy, though. In 1986, Staten Island resident Tom Savino wrote a (hopefully tongue-in-cheek) letter of complaint to the Daily News. "It seems that they turn away many single guys because 'they do not have dates,'" Savino wrote. "How is a guy going to get a date if they refuse to let people in?"

Future stars operated the elevators and swept the floors, and celebrities mingled with clubgoers

Once of the tics that made Danceteria unique was that it tended to focus less on who was famous than on who was probably going to be. Celebrities were woven into the nightly fabric of the club, but the true stars of Danceteria were the people who were on their way up. As such, Danceteria attracted an especially dense population of rising stars, and many of them made ends meet on the venue's payroll.

So if you ever partied at Danceteria, you should've paid close attention to the staff. A young rapper named James Todd Smith, better known as LL Cool J (pictured), and actress Debi Mazar worked as elevator attendants, and the roster of busboys and floor-sweepers included Adam Yauch, Michael Diamond, and Adam Horovitz — collectively known as the Beastie Boys — and artist Keith Haring, whose Barking Dog and Radiant Baby are two of the most recognizable symbols of '80s art.

The legend of Danceteria's star-studded crew has grown over the years to include a couple of icons who probably never worked there. Madonna is often named as a Danceteria coat- or hat-check girl, but this is likely a conflation of her role as a club regular and her job at the Russian Tea Room's hat-check station. Many outlets have reported that Sade Adu, the Nigerian-born, British-raised singer whose band scored Top 10 hits with "Smooth Operator" and "The Sweetest Taboo," tended bar at the club, but music culture historian Tim Lawrence found no evidence that Adu ever worked at Danceteria.

Danceteria crowds were the first in the U.S. to see Nick Cave, the Smiths, Sisters of Mercy, and more

Not long after second Danceteria opened, booking duties fell to Ruth Polsky, a promoter and booker who'd made a name for herself at Hurrah. In his 2015 book "Chapter & Verse," Bernard Sumner of Joy Division and New Order called Polsky the "queen of the New York club scene." Per The New York Times, Gang of Four drummer Hugo Burnham called her "the punk-rock Dorothy Parker."

During her tenure at Danceteria, Polsky booked the first U.S. shows of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, the Smiths, Cocteau Twins, the Cult, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, and Sisters of Mercy, while also stacking the club's lineup with New York-based acts like the Beastie Boys, Kool Moe Dee, Chris Isaak, and Run-DMC. And since she was loved by the musicians she booked and promoted, Polsky was also able to convince celebrities such as Boy George who were beyond Danceteria's budget to patronize the club and mingle with the crowd, creating a dynamic that might have been even more valuable to the venue than having them on stage, according to Tim Lawrence's "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor."

Polsky continued to shape New York's — and therefore the entire country's — music scene until 1986, where she was struck and killed by an out-of-control taxi outside the Limelight. She was 31 years old.

If you were a club scene regular, you already knew the doorman

A night at Danceteria began with getting past the doorman, and on many nights that was Haoui Montaug. Montaug was among those arrested when the original Danceteria was shut down by police in 1980, and he returned for the revival two years later. Montaug was a legend on the New York City club circuit. Besides Danceteria, he had also served as gatekeeper at Hurrah, Mudd Club, Palladium, and even Studio 54. "If a brand-new person he had never seen before came along, in an instant he'd know whether they should be a comp, shown where the secret cloakroom was located, and given a drink ticket or not," marveled Danceteria bartender Chi Chi Valenti, per Tim Lawrence's "Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor." Montaug's influence stretched beyond deciding who would make the cut at Danceteria's door; he also curated a performance-art cabaret show called "No Entiendes," where Madonna made her live solo debut.

According to New York magazine, when Montaug threw himself a "suicide party" while he was suffering increasingly debilitating complications related to AIDS, Madonna joined the event via phone to tell him goodbye. Montaug died the next morning after ingesting a fatal overdose of barbiturates. He was only 39 years old.

Danceteria found ways to confront the AIDS crisis head-on

Second Danceteria opened its doors in February 1982 — seven months before the initialism "AIDS" appeared in medical literature for the first time, in the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Danceteria was not a gay club, but it had close ties to the LGBTQ community: Co-founder Jim Fouratt was a prominent activist who had helped found the Gay Liberation Front in the wake of the Stonewall uprising, and the club often booked performers and other artists who were closely identified with New York City's gay nightlife scene. When the AIDS crisis began to devastate NYC's gay community, Danceteria was among the first venues to host benefit events for people struggling with HIV- and AIDS-related medical expenses.

"The first AIDS benefit was at Danceteria," club co-founder Jim Fouratt said on a podcast called "The History of the World's Greatest Nightclubs" in July 2023. That event was for a drag performer known as Hibiscus who died of AIDS-related complications in May 1982, making him one of the epidemic's earliest casualties. From that night on, Danceteria hosted one event after another to either raise funds for someone living with AIDS or memorialize someone whom the disease had killed. As the decade wore on, AIDS claimed the lives of some of Danceteria's most beloved figures, including artist and one-time club busboy Keith Haring, doorman and programmer Haoui Montaug, and regular Danceteria headliner Klaus Nomi.