Creepy Things About Popular Christmas Traditions And Characters

While Christmas is thought of as the most wonderful time of the year in modern America, full of bright lights and toys and heartwarming movies, that kind of vibe is a relatively modern development. Without electric light and central heat, December is a dark and cold time, and Christmas didn't used to be so focused on children and the family. It used to be a rowdier time of ghost stories and drunken revelry, with everyone doing whatever they could to drive the cold winter away.

Some of these older, darker traditions have survived to the modern day, even if many of them have been toned down for modern sensibilities. Christmas in much of Europe, for example, is full of terrifying monsters out to create havoc for the holiday season, inspired by traditions handed down for generations. But even customs that Americans think of as completely normal and commonplace have weird, dark, or even gross origins. What follows is just a small sampling of the creepier side of Christmas.

Santa began with murder, slavery, and grave-robbing

While Santa Claus isn't a one-to-one copy of the semi-historical Saint Nicholas of Myra, the modern American gift-giver definitely took considerable inspiration from the 4th-century saint. The original Nicholas is one of the most popular saints across the world, and he is considered to be the holy protector of — among many other things — children, sailors, sex workers, and thieves. These aspects of his character come from some of the most popular legends that arose about the saint in the Middle Ages. He becomes the patron of children due to a miracle in which he raises from the dead three students who had been chopped up and put in a pickle barrel by an unscrupulous butcher who wanted to steal their money. His association with gift-giving and sex work comes from the famous story in which he saves three impoverished girls from being forced into sex slavery by throwing bags of gold through their windows in secret to serve as dowries.

Though Nicholas was popular shortly after his lifetime, his cult really took off across Europe in the 11th century after a group of merchant sailors from Bari, Italy, went to the saint's tomb in Turkey, stole his body, and brought it back to Bari, where it remains to this day. Without these stories of murder, cannibalism, sex slavery, and body-snatching, it is absolutely the case that we would not have Santa Claus today.

The child-beating companions of Saint Nick

Thanks to appearances in various bits of American media — including an eponymous 2015 movie — and an increasingly common presence in merchandising, the English-speaking world has come to be fairly familiar with the Krampus in the last two decades. While the American understanding of the Krampus warps the traditional version from Alpine and Central Europe somewhat — such as making him the counterpart of the more familiar Santa Claus rather than the traditional Saint Nicholas — the broad strokes are roughly the same. Namely that Krampus is a dark, furry, horned devil-like creature whose job is to punish the naughty while Santa/Saint Nick rewards the nice. He carries a bundle of switches for whipping children who don't know their prayers and wears a basket on his back to carry off the truly incorrigible children to who-knows-where. In the traditional form, there is not one Krampus, but a whole troupe of them who run the streets or visit children door-to-door on Saint Nicholas Eve (December 5).

Krampus traditions remain strong in the Alpine communities including Bavaria, Salzburg, Tyrol, South Tyrol, and Central European countries such as Czechia and Hungary, where the shaggy beasts are known by various names, including Tuifl, Perchten, Bartl, Ganggerl, and Klaubauf. But while the Krampus is the best-known dark companion of Saint Nicholas, in other regions, the saint might be accompanied by more human figures such as Zwarte Piet, Père Fouettard, Knecht Ruprecht, or Schmutzli.

The cannibal scarecrow of Christmas

While most of Saint Nicholas' companions are not scary, with some of them having evolved into almost entirely benevolent figures, one of the more human companions rivals the Krampus in horror. And to make matters worse, this dark holiday figure is said to have been based on a real person.

Hans Trapp, supposedly the scary sidekick of Saint Nicholas in the Alsace and Lorraine regions of France, is said to have originally been Hans von Trotha, a 15th-century knight known for both his great wealth and relentless cruelty. The story goes that he flooded a town full of people due to a petty dispute with a local abbot. People came to believe that he gained his wealth and even powers of sorcery through a deal with the devil. Ultimately he was excommunicated by the pope and all of his land and possessions were seized.

Legend goes on to say that the now homeless Black Knight made his way to the mountains of Bavaria, where he dressed himself as a scarecrow in order to ambush travelers along the mountain roads. One day his victim was a shepherd boy, whom Hans stabbed, cut to pieces, and cooked for dinner. Just as he was about to take a bite, God killed him with lightning, but his spirit lives on as an eastern French Christmas boogeyman.

The Belly-Slitter

While the Krampus and other dark pals of Saint Nicholas come in the days before Christmas, there is another terrifying Alpine figure who comes in the days after December 25. Her name is Frau Perchta the Belly-Slitter, and she's a kind of dualistic witch-goddess who will just as likely bestow you with favor as, well, slit your belly. Perchta's domain is the 12 days of Christmas — between December 25 and January 6 — during which she roams around with one splayed foot, followed by a train of monstrous helpers, looking for folks who have not kept up with their domestic duties leading up to the holiday season.

Perchta is especially associated with work such as spinning and weaving, so she's especially concerned that households have finished all their fiber work prior to Christmas. Those who haven't finished their work or who try to weave during Perchta's days will find their stomachs slashed open, their guts pulled out, their now-empty torsos stuffed with straw and debris, and their skin sewn back up. In other legends, Perchta and her attendants punish the lazy, the greedy, and the overly curious, such as a servant who was blinded for trying to spy on Perchta through a hole in the wall. However, she and her followers, the sometimes monstrous, sometimes elegant Perchten, can also be benevolent and beautiful to those who do the right thing.

Stinky Greek gremlins

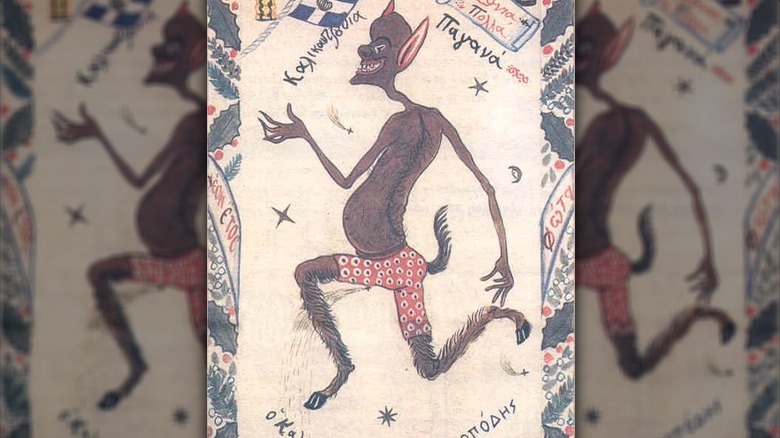

The Alpine region does not hold a monopoly on Christmas monsters, though it certainly has quite a few. It turns out that even Greece finds itself overrun with supernatural troublemakers during the 12 days of Christmas. These little gremlins are known as the kallikantzaroi, and they spend most of the year underground, but they emerge at Christmas when the nights are longest and stick around until Epiphany (January 6), when the local priest blesses the waters. Until then, the kallikantzaroi — variously described as dark, human-sized creatures with iron shoes, or as dark-furred, monkey-like goblins with red eyes — run amok throughout the villages of Greece.

The goblins create the kind of trouble you would expect from a band of drunken hooligans: breaking furniture, scaring people, tipping over food, peeing where they shouldn't pee, trampling flowerbeds, and so on. Fortunately, there are a number of techniques for keeping the kallikantzaroi from sliding down your chimney and doing a number two in your Christmas dinner. They can be warded off with a black-handled knife or a pig's jaw hanging from the door. They can be distracted until sunrise by counting threads in a strand of flax. Many families keep the troublemakers out of their chimney by constantly keeping a fire burning for the 12 days, especially with particularly smoky wood or a stinky old shoe. The worst news, though? People with Christmas birthdays are doomed to become kallikantzaroi.

The Christmas saint who lost her eyes

One of the most popular saints in Scandinavia is the Italian martyr Saint Lucy. As the patron saint of light, her celebration is a welcome sight in the days leading up to Christmas, the darkest time of the year. On Saint Lucy's Day, young girls dress up in white gowns with a (usually) red sash and wear a wreath full of candles on their heads, singing songs and distributing saffron buns. This costume is meant to evoke the holy maiden herself, but the traditional story of Saint Lucy is probably not one you'd want to tell children, let alone have them imitate.

The legends of Saint Lucy say that she was a young girl in Sicily who vowed to remain a virgin in honor of Jesus. When she therefore turned away all the rich young men who came seeking her hand, one rejected suitor angrily snitched on her as a Christian to the Roman magistrates. She was sentenced to be sent to a brothel, but when the guards came to take her away, they found that she could not be moved. She was consequently sentenced to death on the spot, but burning her and gouging out her eyes proved useless until she finally died by being stabbed in the throat. Because of surviving the eye-gouging, she became the patron of light and the blind, and she is often depicted in art holding her own eyes on a plate.

A grumpy, and possibly deadly, gnome

The primary Christmas gift-bringer in much of Scandinavia is known as the Jultomte in Swedish, and in many cases he can appear more or less identical to Santa Claus. However, in its most traditional form, the tomte is a helpful but curmudgeonly (and easily offended) guardian of the family farm. Looking roughly like a garden gnome — elfin in size with a white beard and a pointed red cap — the tomte lives in the family barn and helps with barn chores such as feeding the animals, milking the cows, and carrying giant loads with his prodigious strength. But heaven help you if you offend him.

In order to help keep the tomte appeased, it is traditional to set out food offerings, especially at Christmas, when the standard gift is a big bowl of rice porridge with a pat of butter on top. Missing out on this offering or doing it wrong can have deadly consequences. In one famous story related by John Lindow's "Swedish Legends and Folktales," a family put the butter on the bottom of the porridge and the tomte killed their prize cow in anger. Then he ate the porridge and found the butter at the bottom, and in remorse stole a neighbor's cow to replace the one he killed. In another story, a servant girl eats the tomte's porridge herself and is magically forced by the tomte to dance herself to death. Such tales are, arguably, not very Santa-like.

Caroling used to come with threats of violence

One common Christmas custom used to spread cheer throughout a neighborhood is caroling, where a small group of people go door to door singing songs like "We Wish You a Merry Christmas" before hustling down the sidewalk to the next house. But while these days caroling is typically done just in the spirit of the season (or maybe in hopes of a small charitable donation), caroling — and its antecedent, wassailing — was not always done strictly out of the goodness of one's heart. Carolers and wassailers in centuries past often expected some form of generosity from those receiving their little Christmas display, whether that be in the form of food, drink, or money. And sometimes this expectation was backed up with threats of violence.

According to Stephen Nissenbaum's "The Battle for Christmas," a court record from 1679 shows that a band of rowdy young men had come to a house seeking reward for their (probably terrible) music, and when they were refused, they threw rocks and garbage at the house for an hour and a half, broke down part of the fence, kicked open the cellar door, and stole multiple barrels of apples. Other groups were known to force their way into homes that didn't welcome them in for food and drink. Even the songs they sang reflected such a threat: "[I]f you don't open up your door,/We'll lay it flat upon the floor."

Mistletoe is gross, actually

Kissing someone under the mistletoe is an experience that is practically synonymous with Christmas in some cultures, but the reason why this parasitic little plant is associated with romance is something of a mystery. We don't even know for sure where the word "mistletoe" comes from, but it might come from a Germanic word meaning "poop twig." Romantic already. Some have posited that the plant's connection to kissing might come from the famous Norse myth where Loki tricks a blind god to kill the god Baldur with a mistletoe arrow. In some versions, Baldur's mother Frigg cries tears that turn into mistletoe berries, and she decrees that the plant will thereafter be a symbol of love.

But even completely separate from that tradition, mistletoe has long been associated with fertility and vitality. For one thing, it stays green during the winter, making it a natural symbol of eternal life. The connection with fertility is only strengthened by the fact that the seeds of the mistletoe are white and sticky, just like a certain fertility-related bodily substance. As described in Annals of General Psychiatry, the ancient Greeks, who celebrated the plant for its perceived healing abilities, referred to mistletoe juice as "oak-sperm" and saw the process of harvesting it from its host tree as, ahem, literally removing the twig and berries from the tree. Let that image play in your mind when you bump into your crush under the mistletoe bough.

Murdered King Wenceslas

A popular English-language carol that might cause some folks to scratch their heads is "Good King Wenceslas," in which the eponymous king sees a poor man scrambling in the snow for firewood "on the Feast of Stephen." The king then goes out with his page to bring food and fuel for the poor man, and the two are kept miraculously warm by the glow of the king's holiness. It's possible this raises some questions for you. What's the Feast of Stephen? That's the easy part. That's December 26, the day after Christmas, the feast day of Saint Stephen, the first Christian martyr. But who is King Wenceslas that we celebrate with a jaunty little tune every holiday season?

Well, first of all, he wasn't a king. He was the duke of Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic) in the 10th century. He was raised by his grandmother Ludmila, who taught him to be a Christian, but while Wenceslas was still a child, his pagan mother had Ludmila killed and took over the throne of Bohemia until Wenceslas came of age. Wenceslas was known for his piety and generosity, as celebrated in the popular carol, as well as a pacifism that made him unpopular with the nobles of Bohemia, including his own younger brother, Boleslav the Cruel. Boleslav intercepted Wenceslas on the way to mass and murdered him right at the church door.

The Nutcracker is darker than you think

A beloved Christmas tradition across much of the world, especially among children, is going to see a performance of "The Nutcracker," the Christmas-themed ballet with music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. But while Tchaikovsky, with his festive melodies and Sugar Plum Fairy, might be the name most associated with the tale of a little girl whose Christmas present comes to life, he is not the originator of it. In fact, the story of the Nutcracker was first told in the book "The Nutcracker and the Mouse-King" by E.T.A. Hoffmann, a writer better known for spooky tales of dark fantasy.

In that vein, the original "Nutcracker" story had a darker tone than what has ended up on the ballet stage. Hoffmann's tale is about a poor young man transformed into a nutcracker after messing up his attempt to save a spoiled princess from a curse, who is then given as a gift to a young girl by her fairly sinister godfather. While the girl has to hustle to keep her brother from tormenting her new present like that weird kid from "Toy Story," the nutcracker has to protect the girl from the attacks of a seven-headed mouse king who seeks to kill the nutcracker in revenge for the death of his mother, the mouse queen. Some elements of that have survived to the ballet, but the book has way more murders and monsters.