The 1931 Assassination Of Mob Boss Salvatore Maranzano

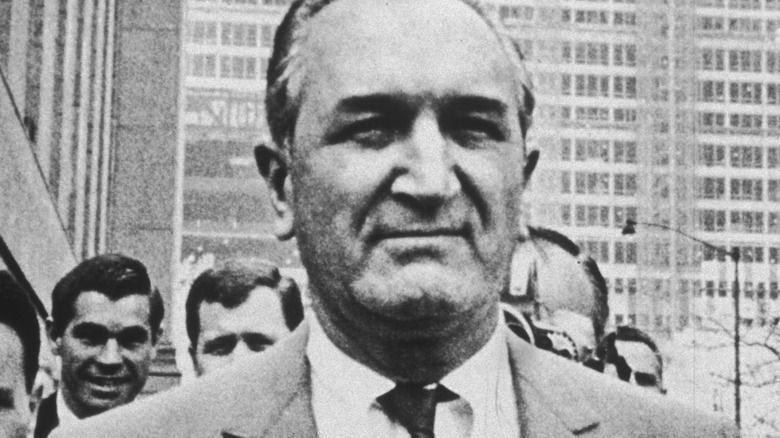

One of the most pivotal figures in the history of the American Mafia is also one of its most mysterious — fitting, given its status as an ostensibly secret criminal organization. There are no verifiable photographs of Salvatore Maranzano except from the crime scene of his murder. His exploits in Sicily and America are known through second-hand accounts by underworld cronies and enemies, whose own deeds have overshadowed Maranzano's in popular accounts of the history of organized crime in the Italian diaspora. Yet the careers of such Mafiosi as Lucky Luciano and Joseph Bonanno seem to have been greatly shaped by their connections to Maranzano.

According to Salvatore Lupo's "History of the Mafia," Maranzano was 43 when he immigrated to the United States in 1927 and was already a formidable presence in the Sicilian Mafia. Once stateside, he quickly became a major force in bootlegging operations in the New York area. Unlike many of his associates, Maranzano was reportedly well-educated and enjoyed demonstrating his knowledge of the Roman Empire, as well as his fluency in Greek and Latin (per Selwyn Raab's "Five Families"). Awed associates called him Don Turriddu.

"Don Turriddu" eventually became the chief rival to Joseph Masseria, sparking the underworld conflict known as the Castellammarese War (named for the area of Sicily Maranzano and his top aides hailed from). Maranzano's ambition, bearing, and manpower kept him alive throughout the fight, but they also helped seed his eventual murder at the hands of people he thought had become his allies.

He came out on top in a gangland war

In the world of organized crime, Salvatore Maranzano was a hero to some of his Sicilian-American cronies. In his memoir, "A Man of Honour," Joseph Bonanno was effusive in his praise for Maranzano: handsome looks, pleasant voice, an education for the priesthood, and a bold and ruthless fighter. Bonanno was one of Maranzano's chief lieutenants in the Castellammarese War, sparked by the resistance of Maranzano and other Mafiosi to tributes demanded by the family headed by Joe "The Boss" Masseria.

That, at least, is the traditional explanation for the gangland flight. The truth may have been more complicated; David Critchley presented evidence in his "The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891-1931" that Maranzano might have been the more ambitious aggressor of the two, seizing on underworld disputes in New York and around the country as a pretext. Whatever the causes, the war went on for months, costing both factions money and manpower. With Masseria on the losing side, his chief aide, Lucy Luciano, agreed to set his boss up for a hit if Maranzano would agree to a cease-fire and recognize Luciano as Masseria's successor and a boss of equal stature to Maranzano himself (per Selwyn Raab's "Five Families").

Maranzano and his men didn't even need to dirty their own hands to get rid of Masseria — Luciano invited his boss to lunch and conveniently excused himself before his own killers came in blasting.

Maranzano undermined his own victory

After seeing his rival Joe "The Boss" Masseria betrayed and dispatched, Salvatore Maranzano became the chief Mafia leader in the New York area. Because of the city's significance to Sicilian and Italian criminal organizations throughout America, Maranzano summoned leaders from around the country to a meeting in Wappingers Falls in 1931 (per Selwyn Raab's "Five Families"). By some accounts, this meeting marked the beginnings of the modern structure of Mafia families, patterned after Roman legions by Maranzano personally. Other evidence suggests the conference established only modest adjustments to membership requirements. But it is generally accepted that Maranzano used Wappingers Falls as a platform to assert his supremacy over the New York Mafia and, by implication, all Italian-American criminal enterprise.

This move surprised and disgusted other Mafia bosses, particularly Lucky Luciano. Luciano expected to be left alone to run his own family afterward — not subject to Maranzano's influence. According to "The Origin of Organized Crime in America," Maranzano further strained relations with Luciano by becoming embroiled in racketeering disputes with Luciano's Jewish allies in the garment district.

Even Maranzano's underlings and admirers felt he was out of step with other Mafiosi in 1931. Besides his imperious manner, there were cultural and linguistic barriers that kept him from effectively communicating with his fellow gangsters and maintaining alliances.

He died from betrayal and deceit

Who planned to kill who first in the contest between Salvatore Maranzano and Lucky Luciano after the Castellammarese War remains a mystery. It's been suggested that Luciano might have wanted to wipe out Maranzano and his own boss, Joe Masseria, from the start of the war, but he remained in Masseria's camp for months and seemed content after changing sides until Maranzano tried asserting authority over him. On the other hand, some gangland testimony, as recorded in "The Origin of Organized Crime in America," suggests that Maranzano put Luciano, Al Capone, Frank Costello, and other Mafiosi on a hit list for being insufficiently trustworthy or malleable. He extorted tribute payments from other families that were squirreled away as a war chest.

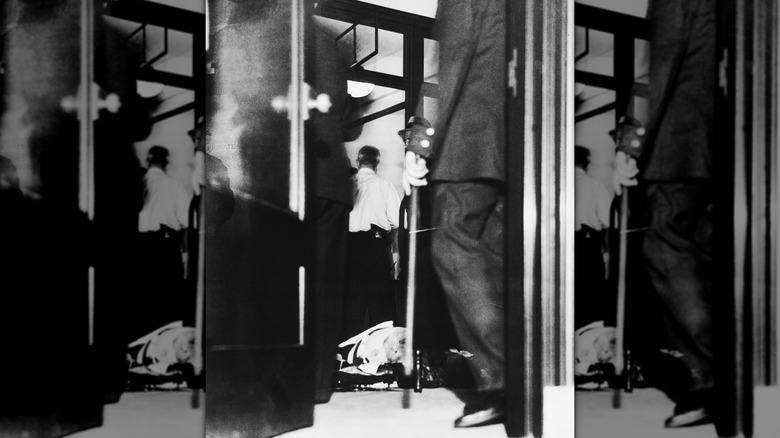

That Maranzano was scheming to kill him became Luciano's justification for what came next. Per Selwyn Raab's "Five Families," Tommy Lucchese, a Maranzano associate who was also Luciano's friend, alerted Luciano to the plot. In retaliation, the two of them recruited Irish gunmen and disguised them as IRS agents; Maranzano expected to be audited and had his bodyguards go without guns to dodge weapons charges. On September 10, 1931, the gunmen arrived in Maranzano's office and, after Lucchese singled the boss out, shot and knifed him to death.