People Convicted Of Murder Even Though A Body Was Never Found

As comforting as it might be to think of justice as something righteous and rooted in a strong sense of right and wrong, the reality is often very different. As history has repeatedly proven, justice can often be messy or belated, muddled by complicating factors that can often leave you wondering whether or not punishments were even served to the truly guilty parties.

There are many ways that justice can get complicated, and it's more than likely you already have your own thoughts on situations where justice wasn't served. But there's a particular kind of situation that's existed throughout history and which has, on more than a few occasions, brought with it a fair amount of controversy — murder cases and rulings made in the absence of a body. It's a situation that crops up perhaps more often than you'd expect, and when it does, it often proves to be either mysterious or harrowing, always a strange case in one way or another, and that's putting it lightly. Fittingly, the rulings in these sorts of cases really run the gamut, with convictions sometimes seeming well-earned, or completely unfounded, based purely on the kinds of evidence presented.

Murder convictions without a body are certainly strange; here are a few of them throughout history.

The following article includes allegations of domestic abuse, sexual assault, and child abuse. If you or anyone you know needs help with these issues, help is available. You can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1−800−799−7233, and can find more information, resources, and support at their website. For victims of sexual assault, help is available at the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673). If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

Andras and Agnes Pandy

The case of the so-called "Diabolical Pastor" is certainly a terrifying and disgusting one. As the story goes, Andras Pandy moved to Belgium to find work as a pastor in 1956, around the time that he married Ilona Sores, and all seemed well. At least, until Sores suddenly disappeared in 1967. Andras remarried in 1979 — this time to a woman named Edith Fintor — only for Fintor to also disappear around 1986.

The truth didn't come out until 1997, with Agnes Pandy (Andras' oldest daughter) finally confessing. Despite his guise as a mild-mannered pastor, Andras was an incredibly controlling patriarch who began sexually abusing Agnes when she was only 13. She was forced into being her father's accomplice and confessed to being complicit in five murders — Sores, two of Agnes' brothers, and Fintor and one of her daughters. But investigators couldn't find those bodies, as Agnes confessed to helping her father chop up those bodies to take them to the local slaughterhouse, or dissolving them in a huge vat of acid. Regardless, the testimony was more than enough, even with the lengths Andras had gone to in covering up his crimes; Agnes was given 21 years in prison, and he was given a life sentence.

That said, several skeletons were found behind one of Pandy's homes, and both bone fragments and chunks of flesh were found in the flooded basement. None of them were confirmed to be the remains of the family, though, leading to the possibility of there being more victims.

Joseph Marie Guillaume Seznec

The Seznec Affair is one of France's most controversial court cases, and for good reasons. Joseph Marie Guillaume Seznec was a sawmill owner who took a trip from Brittany to Paris with a business partner named Pierre Quemeneur on May 25, 1923. The two were meeting Boudjema Gherdi regarding the sale of 100 Cadillacs, but their car started breaking down, and Quemeneur elected to take a train. He reportedly sent a telegram from Le Havre and left a bill of sale to Seznec for his estate, and then he was just gone. He was presumed dead, and Seznec became the prime suspect for his murder, with prosecutors claiming he'd made up Gherdi as a cover story. Long story short, Seznec was declared guilty and sent to a prison colony.

But Seznec always claimed he was innocent, as has his family. They've long held that the incriminating bill of sale was fake, and that's not mentioning the fact that Gherdi was, in fact, real. Not only that, but during World War 2, he was an informant for Pierre Bonny, the investigator on Seznec's case who was kicked out of the police for falsifying evidence and later joined the French Gestapo. Shortly before his execution in 1945, Bonny apparently even confessed to sending an innocent man to a prison colony.

In 2018, new evidence even arose, implying that Quemeneur might have been killed by Seznec's wife, who was defending herself from his advances. Despite all of that, though, French courts have repeatedly refused to reopen the case.

Saevar Ciesielski

The case of the Reykjavik Confessions is certainly a twisted one, starting with the disappearance of Gudmundur Einarsson in January 1974, somewhere in the snow-covered, rocky land of the Reykjanes Peninsula. People thought little of it, until another disappearance that November, this time regarding Geirfinnur Einarsson. Geirfinnur had disappeared under somewhat odd circumstances, having gone out to the peninsula to meet a mystery caller, then never returning. Police followed rumors that led them to small-time crook Saevar Ciesielski, and lengthy interrogations also brought Ciesielvski's friends (Kristjan Vidarsson, Tryggvi Leifsson, Albert Skaftason, and Gudjon Skarphedinsson) and girlfriend Erla Bolladottir onto their radar. In the end, despite a lack of physical evidence — including a lack of bodies — all six of them confessed to both crimes.

But this was far from a simple case. Those aforementioned interrogations? They lasted over the course of months and years, during which all six were kept in solitary confinement, denied sleep, and (at least in the case of Ciesielski) physically tortured. Reports from some of the accused revealed that many of them had foggy memories of what happened — most likely due to the drugs they were given, supposedly to help them sleep, but more likely to make them especially pliable. Eventually, all of them had either decided that confession was just the easiest way out or even been convinced that they had committed murder. All despite the fact that they hadn't, though it wasn't until the 2010s when the courts officially recognized that their testimonies had been false and coerced through torture.

Peter Reyn-Bardt

Here's a pretty strange story — one that involves the discovery of a body, but not the one you'd expect. The whole thing started in 1959 with the meeting between Malika de Fernandez and Peter Reyn-Bardt, which turned into marriage within just four days. Things fizzled out just as quickly, though, with Fernandez traveling the world, while Reyn-Bardt stayed back home in England. Within a couple of years, Fernandez had disappeared. Police suspected Reyn-Bardt, but without any actual evidence, their investigation didn't get very far.

The case went cold until 1983, when workers at a peat processing facility happened upon an odd shape that had been pulled from the bog near Reyn-Bardt's home. To their surprise, it was the head of a woman, perfectly preserved by the bog's unique chemical environment. With initial reports saying that the head was from a woman between 30 and 50 years of age, investigators immediately turned to Reyn-Bardt, who quickly confessed, saying he'd accidentally killed Fernandez in 1960 after she threatened to blackmail him for being gay (still a crime back in 1960s England).

But here's the twist: After further analysis, investigators found that the head didn't belong to Fernandez. It belonged to a woman who'd died centuries earlier. Back in Roman times, actually. Reyn-Bardt tried to take back his confession but was found guilty, and prosecutor Martin Thomas summed up the situation perfectly, saying, "But the supreme irony is this: [The] discovery led directly to the arrest of the defendant and to his detailed confession" (via UPI).

Robert Peter Russell

Shirley Gibbs Russell was an accomplished captain in the United States Marine Corps with a bright future to come, but in March 1989, she suddenly disappeared from her apartment on the military base in Quantico, Virginia. Clearly, these were strange circumstances, and suspicions immediately turned toward her ex-husband, Robert Peter Russell, with the prevailing theory being that he shot her, then dumped her body in a mine. The only problem? There wasn't a shred of physical evidence to be found — no murder weapon, no bloodstains, and no body. What's more, Russell had his own story prepared to try and maintain his innocence, saying she'd just wanted to leave her military life, disappearing entirely on her own, and witnesses later claimed to see her after the date of her disappearance.

Fortunately for the prosecution, though, they had some pretty compelling evidence, even if it was technically circumstantial: a supposed novel that Russell had been working on with his mother, in which a character kills the wife of a Marine. The manuscript ultimately outlined a 26-step murder plan, including details like "Make it look as if she left" and musings on how exactly to pull everything off. Coincidence? It certainly didn't seem to be; it felt less like a piece of fiction, and more like the notes for a real-life evil scheme. Combine that with a witness who testified to Russell confessing his murderous intent (and ideas for a sneaky coverup) some months before, and in the end, he was convicted.

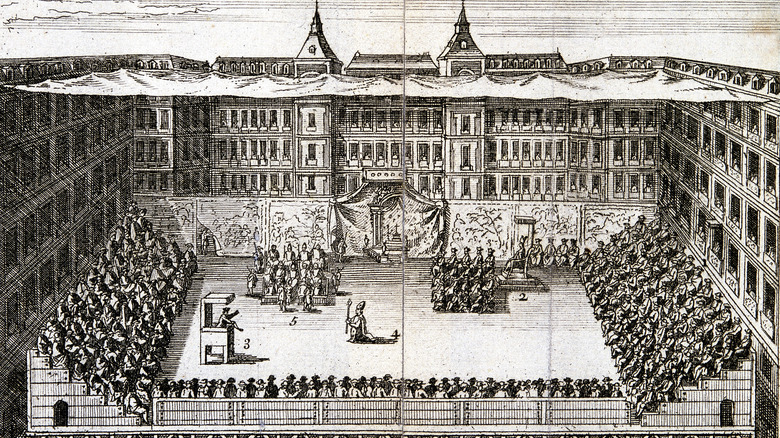

Yuce Franco; Moses Abenamias; Juan de Oraña; Alonso, Juan, García, and Lope Franco

The Spanish Inquisition is an entire topic all on its own — one that's too complicated to cover in full at the moment. But here's the gist: The Inquisition was an institution started in the 15th century, which claimed to strive for religious unity in Spain. In practice, though, the whole thing turned into a thinly-veiled guise for anti-semitism, with one of the most infamous figures of that time being Tomás de Torquemada.

Torquemada became known for his bloody leadership, taking the already-discriminatory basis for the Inquisition even further by actively vilifying Jewish people (including those who had publicly converted to Christianity). And that's where the Holy Child of La Guardia comes in. The whole affair involved the supposed kidnapping and murder of a 7-year-old boy, whose body was apparently used for some kind of magical ritual. Seven people (Yuce Franco; Moses Abenamias; Juan de Oraña; Alonso, Juan, García, and Lope Franco), all of whom fell into the groups that Torquemada was looking to target, were accused. They were tried shortly after and convicted in late 1491, after which they were burned at the stake, and the child was recognized as a saint.

But it was fabricated for political effect. The confessions were extracted through the use of torture and were wildly inconsistent, until investigators forced the accused to agree on one story. Not only that, but the child's body was conveniently never found, and actual details on his identity are scarce.

Leonor and João Cipriano

When you look at the official statement regarding the disappearance of 8-year-old Joana Cipriano from the small town of Figueira, Portugal, back in 2004, you'll find a bloody and horrific tale of the girl's mother and uncle — Leonor and João Cipriano. It's one that involves murder, then the disposal of the evidence by cutting apart Joana's body and feeding it to the pigs, and the eventual ending with both Leonor and João being convicted for the crime and sentenced to prison.

But, as it turns out, the story doesn't end there. In 2007, the disappearance of Madeleine McCann — who vanished from Praia de Luz, Portugal, just 10 miles away from where Joana was last seen — was all over the news. Once again, the parents were immediately blamed, Kate and Gerry McCann in this case, despite a lack of real evidence, and that started turning heads.

In fact, both investigations were led by the same man, Goncalo Amaral, who would eventually be kicked off the McCann case after some digging led to the discovery that he'd falsified evidence in the past. More specifically, he'd covered up the use of torture to coerce a confession from Leonor Cipriano, something that had gone unnoticed at the time because the Ciprianos didn't have the money or platform to raise the alarm, even though Leonor had come back from interrogations beaten and bruised. (She would later retract her confessions, but to little effect.) The methods certainly call the Ciprianos' convictions into question, leaving plenty of mysteries surrounding both cases.

Giovanni Brusca

Sometimes, when people are found guilty of a murder in which no body has been found, that fact is enough to invite questions. But at other times, the case involves the mafia, so there are fewer mysteries and far more horrors.

This particular case had a couple of years of buildup, starting in 1992 with the brutal murder of Giovanni Falcone, a Sicilian judge who was openly fighting against the presence and power of the mafia. Falcone was killed by the infamous Cosa Nostra clan, but law enforcement managed to get their hands on one of the mafia's assassins, Santo Di Matteo, who ultimately became a police informant. Turning against the mafia is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a dangerous decision — something which became abundantly clear in 1993 when Di Matteo's 11-year-old son Giuseppe was apparently approached by police officers promising to take him to his father. Except these weren't police officers; they were mafia members in disguise, intending to threaten Di Matteo out of testifying.

They held Giuseppe for about two years, starving, beating, and generally torturing him, until Giovanni Brusca — a high-ranking mafia boss with the grisly nickname of "the people slayer" — personally saw to it that the boy was strangled to death. And, not only that, the body was then dissolved in acid, a brutal and long-standing mafia tradition that both destroyed evidence and aimed to further hurt the family of the victim. Brusca was eventually sent to prison after confessing to over 100 murders, but this one certainly stands out.

Anthony John Allen

If there's one thing that can be said about Anthony John Allen, it's that he was apparently quite adept at weaving a web of lies. As far as investigators can tell, Allen's family mysteriously disappeared in May 1975. According to Allen himself, he fought with his wife Patricia Allen, and she walked out on him, taking the kids with her and enlisting help from a man named Johnny Simone in order to book passage to the U.S. Her car was later found abandoned, sparking suspicion, but without much evidence, investigators let the case go cold.

The case wouldn't be reopened until 2001, when some concerning details began to come to light. For one, Allen had never been on the best terms with the law, having faked his death in 1967 to dodge a prior shaky marriage and money issues; that whole ordeal ultimately saw him convicted for bigamy (and that's aside from over 100 counts of theft). But beyond that, a bit of investigation found that Simone had suffered a stroke in 1972; he couldn't possibly have helped Patricia. So it was clear that Allen had made up a tale to tell, and the court couldn't see any reason for him to do so, other than as a coverup for murder, leading to his conviction.

That said, no one could fully overlook the fact that the bodies had never been found, and Allen was never keen on giving up any information; he always claimed to be innocent, the victim of injustice.

John, Richard, and Joan Perry

The story behind the conviction of John, Richard, and Joan Perry is more popularly known as "The Campden Wonder," and it turns out the name is quite fitting. It starts with the elderly rent collector William Harrison, who left his home in Chipping Campden, England, in August 1660. When he didn't return, his servant, John Perry, was sent to look for him. Perry was gone for a couple of days, after which Harrison's ripped and blood-stained clothing was discovered.

Local authorities were suspicious of Perry, who suddenly started accusing his brother and mother (Richard and Joan Perry) of robbing and killing Harrison, then dumping his body in a river. After two separate court trials, all three Perrys were found guilty of murder and hanged in 1661, despite no body being found, Richard and Joan always maintaining their innocence, and John eventually admitting that the story he'd told had been fiction.

But here's the truly strange thing: While no dead body was found, a living one was. As in, Harrison was never dead, making his dramatic return in 1662. According to him, he'd been rather suddenly abducted and tossed onto a ship headed for Virginia, only for his captors to be bested by Barbary pirates. He was forced into servitude in the Ottoman Empire but made a daring escape, even sneaking his way onto ships that eventually saw him back to England. The stuff of fiction, perhaps, and just how much of it was true is still a matter of debate.