The Dark Side Of The 1960s Music Industry

Overall, the 1960s was an optimistic and groundbreaking decade for music. Rock 'n' roll was in full stride, Motown Records gave Black artists a mainstream voice, and protest songs advocated for civil rights of all kinds. London – widely considered the epicenter of such forward-thinking initiatives – was experiencing its "Swinging Sixties," characterized by opposition to the norm, the sexual revolution, and myriad artistic endeavors.

Musical acts born of this scene included The Rolling Stones, Dusty Springfield, and, most famously, The Beatles. The influence of such artists – and their associated progressive ideals – soon spread to other regions in a phenomenon that became known as the British Invasion. But, unfortunately, it wasn't all free love and groovy vibes.

The '60s was also a time of great upheaval, with events like the Vietnam War and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and President John F. Kennedy shocking the world. Naturally, this dichotomous energy found its way into the decade's music. From censorship and sexism to rampant substance abuse to horrific murders, here is the dark side of the 1960s music industry.

One DJ took the blame for a decade of payola

In the 1950s, being an American radio disk jockey was a lucrative career. Rock and R&B music had taken off and artists were churning out more singles than ever. As a result, many record executives – keen to make sure their artists were played – resorted to the shady practice of pay-for-play, also known as payola.

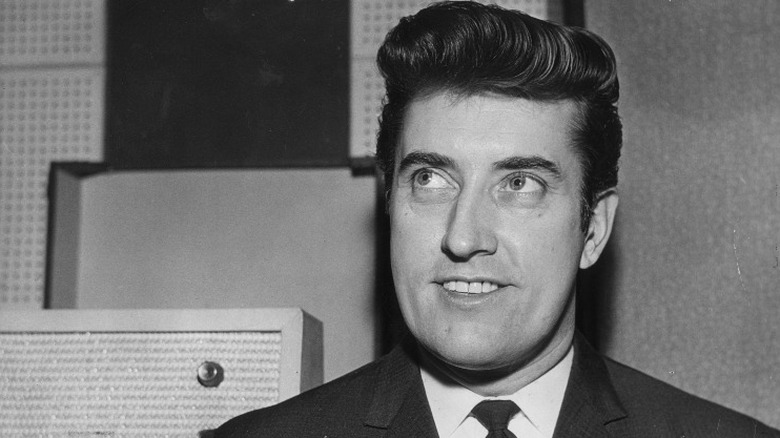

By slipping DJs a few extra dollars, record companies could all but ensure that their artist's song would become a hit – something many DJs thought of as plain old business. But at the end of the '50s, authorities began taking a closer look at the practice. Following several highly publicized trials in the U.S., Congress declared payola a criminal act in 1960. Amidst the chaotic hearings, two of America's most popular DJs – Dick Clark and Alan Freed (pictured) – came into question.

Both Clark and Freed denied ever having accepted under-the-table payments in exchange for radio play. But everyone was more inclined to believe the dapper, all-American Clark – despite his having recently off-loaded several incriminating assets – than the defiant and unabashedly blunt Freed, who popularized the term "rock 'n' roll" and regularly advocated for Black artists. While Clark walked away relatively unscathed, Freed was charged with commercial bribery, heavily fined, and fired from his job. He died virtually penniless of complications related to alcoholism just three years later.

Songs about teenage tragedy were all the rage

In 1955, The Cheers' calamitous song "Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots" seemed to predict the early death of actor James Dean in a car accident. As a result, the song – which fanned the public's fascination with dying young – saw overnight success. The music industry was quick to capitalize on the new trend, and, thus, the teen tragedy song was born.

Also called "splatter platters" and "death discs," these edgy pop songs featured curiously upbeat music juxtaposed with ominous lyrics depicting teenagers meeting untimely deaths in car crashes and via other methods, usually as a result of their irresponsible behavior. Teen tragedy songs were a bizarre take on the murder ballads of country and folk, which similarly served as cautionary tales designed to keep young women from shacking up with bad boys.

The popularity of the morbid genre reached an all-time high in the early 1960s. Songs like The Shangri-Las' "Leader of the Pack" – in which a break-up causes the singer's rogue boyfriend to die in a motorcycle accident – and both Wayne Cochran's "Last Kiss" and Jimmy Cross' "I Want My Baby Back" – which depict dates turned deadly following car accidents – became huge hits. Many agencies forbade such death-obsessed songs, but this only made the genre even more popular – particularly with rebellious youths.

People couldn't handle female musicians being openly sexual

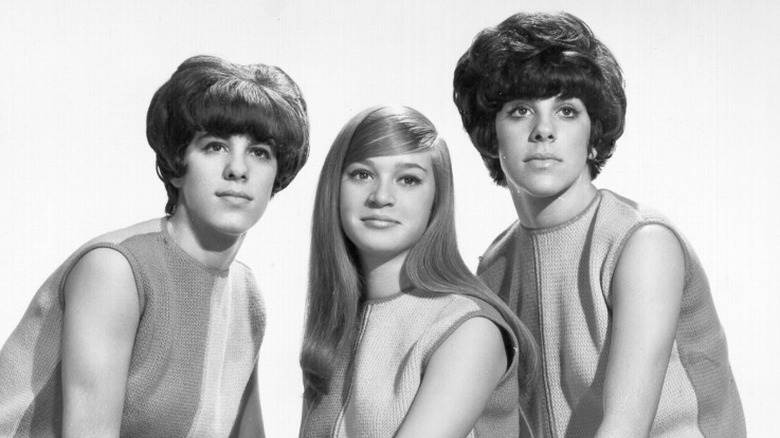

The 1960s saw a major cultural shift toward female sexual liberation – but it certainly didn't come easily. The so-called "sexual revolution" kicked off in 1960 when the then-newly invented birth control pill became more widely available, giving women the freedom to engage in casual sex. That same year, The Shirelles – a Black all-girl group – had a hit with their seemingly-innocent song "Will You Love Me Tomorrow."

Though written by a young married couple – Carole King and Gerry Goffin – the song is sung exclusively by women, which caused major controversy given its suggestive lyrics. Lines like "Is this a lasting treasure or just a moment's pleasure?" candidly discuss female sexuality and casual intimacy – topics that had not previously been so openly explored in pop music, let alone by members of the fairer sex. Deeming it too scandalous for the public, many American radio stations banned the song.

Nonetheless, music continued to fuel the female sexual revolution as the '60s wore on, with hit songs like Lesley Gore's "You Don't Own Me," Martha & The Vandellas' "Heat Wave," and Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin's "Je t'aime... moi non plus" – as well as the female-driven frenzy of "Beatlemania" – further establishing women as free-thinking members of society motivated by their own desires.

Sam Cooke was murdered under bizarre circumstances

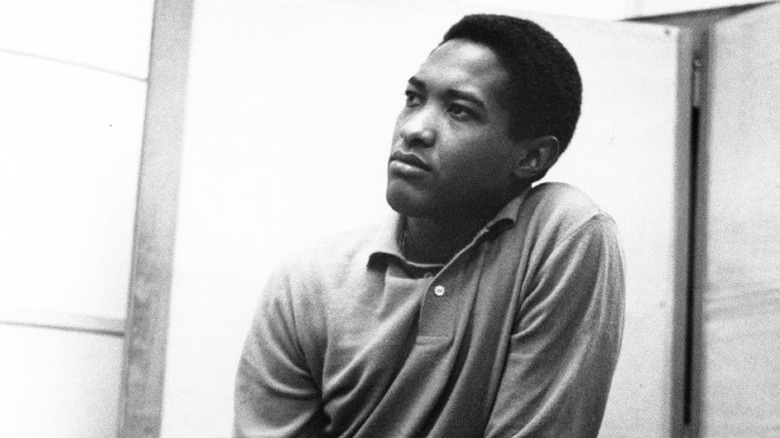

Known as the "King of Soul," Sam Cooke popularized R&B and soul music in the 1950s and early '60s through his accessible hits like "Cupid," "You Send Me," and "(What A) Wonderful World." By age 33, Cooke had 29 singles and a newly acquired record label under his belt. But, unfortunately, his career – and his life – ended far too soon.

On December 11, 1964, Cooke checked into the Hacienda Motel in Los Angeles, California with Elisa Boyer, a young woman he had met that night in Hollywood. A little later, motel manager Bertha Franklin claimed that Cooke – wearing only a single shoe and a jacket – confronted her asking where Boyer was in such a brusque manner that she shot him in self-defense, killing him. Police received two calls about the incident: one from the motel's owner and another from Boyer, reporting her alleged kidnapping and near-rape from a phone booth.

Based on these accounts, police deemed Cooke's death a justifiable homicide. But many weren't convinced. Witnesses suggested that Boyer – later convicted of murder – may have been robbing Cooke. Meanwhile, Cooke's family and friends disputed the given versions of events, implying that his manager – or enemies he made as a civil rights activist – had carried out a murder plot. What's worse, singer Etta James and others commented on the horrific and extensive injuries visible at Cooke's open-casket funeral, none of which fit the story provided.

Censorship was a constant problem

Progressive musicians pushed the boundaries of society in the 1960s and government agencies often resisted these perceived attacks on morality. In the United States and Britain, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) found themselves busier than ever attempting to censor songs that featured lyrics with curse words, slander, overt sexuality, promotion of drug use, or other scenarios they deemed obscene.

Many '60s songs fell on the wrong side of the agencies' rules and were denied airplay for fairly obvious reasons – take, for example, the blatant sexual innuendo of The Rolling Stones' "Let's Spend the Night Together" – but other cases were more perplexing. Some considered the condemnation of wholesome songs like Peter, Paul, and Mary's fantastical "Puff the Magic Dragon" – allegedly an elaborate drug metaphor – and The Beach Boys' "God Only Knows" – deemed blasphemous for merely mentioning God in a rock song – a bit of a stretch, not to mention that whole business of the FBI investigating The Kingsmens' "Louie Louie" for its indiscernible-therefore-possibly-obscene lyrics.

But by far the most extreme example of '60s censorship came from Brazil. Artists like Caetano Veloso (pictured) and Gilberto Gil – who created music as part of the Tropicália artistic movement – faced opposition from the country's military dictatorship, which found the music anarchistic. Both were imprisoned for months, banned from performing, and later exiled from Brazil.

The Beatles incited the rage of religious groups

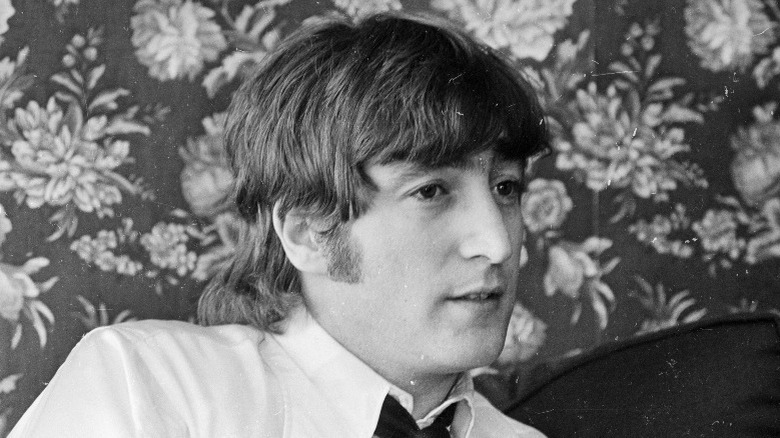

Formed in Liverpool, England, The Beatles – heavily inspired by American rock 'n' roll – quickly grew to become a worldwide sensation in the early 1960s. The band became so popular, in fact, that fans – particularly women – were driven to the screaming hysteria known as "Beatlemania" whenever the four men made a physical appearance.

The group's rise to fame was so sudden and intense that singer-guitarist John Lennon was inspired to comment on it. In a conversational March 4, 1966, interview with the London Evening Standard, Lennon casually shared his thoughts on religion with his friend, reporter Maureen Cleave. "Christianity will go," he explained, adding, "It will vanish and shrink. I needn't argue about that; I'm right and I will be proved right. We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first – rock 'n' roll or Christianity."

The interview ran without incident in England. But his candid musings quickly evolved into a PR nightmare in America when part of his quote – the bit about The Beatles being "more popular than Jesus" – made its way into the teen magazine DATEbook that July. Religious groups – particularly fundamentalist Christians – were outraged, boycotting the band, publicly burning records, and citing Lennon's words as proof that rock music was inherently evil. Eventually, the rage even inspired death threats and a reluctant Lennon issued a formal apology.

The authenticity debate got ugly

Throughout the 1950s, the music industry standard was mass-producing hit songs using a songwriting team and polished session musicians, then presenting them to the masses with an attractive pop star figurehead. But, in the '60s, The Beatles broke the mold by writing and performing their own songs inspiring discussions about the merit of musical authenticity.

In fact, a desire for authenticity spawned the folk revival movement of the early '60s. It was, at its core, a stripped-down, acoustic-only opposition to the glitz and glam of the music industry machine. So, imagine everyone's horror when one of folk's most beloved figures – Bob Dylan – employed the use of an electric guitar in the summer of 1965. The betrayal audiences felt was so great that, amidst the nightly sea of "boos," someone was even heard calling Dylan "Judas" at an England show.

Then came The Monkees (pictured). Manufactured in America to capitalize on the popularity of The Beatles, The Monkees – a fully casted and "made-for-TV" band – were seen by many as the antithesis of authenticity. Unlike The Beatles, who were all capable musicians, The Monkees were all for show – literally. They came prepackaged with a television show – which focused mostly on their banter – and a prolific songwriting team. Though they later attempted to reclaim authenticity by writing their own songs, most never viewed them as real artists.

Several musicians died in plane crashes

Musicians spend a lot of time traveling, often relying on airplanes to get places quickly. But, unfortunately, flight technology was far less reliable in the 1960s. Still reeling from the 1959 deaths of Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens in a plane crash – an event that became known as "The Day the Music Died" – the music world was dealt several more blows in the '60s.

On March 5, 1963, country music star Patsy Cline – along with fellow musicians Cowboy Copas and Hawkshaw Hawkins – boarded a small plane for what was supposed to be a quick flight home to Nashville, Tennessee following a Kansas City, Missouri show. Cline's manager and pilot, Randy Hughes, became disoriented in cloudy conditions and crashed into the ground, killing everyone on board. Then, on July 31, 1964, country music lost another star when Jim Reeves, piloting his own plane, flew through a storm and wrecked near Nashville, killing himself and his piano player, Dean Manuel.

Soul singer-songwriter Otis Redding (pictured) was at the top of his game in the late '60s, with Aretha Franklin's rendition of his song "Respect" topping the charts. In fact, he was traveling from a television appearance in Cleveland, Ohio to a concert in Madison, Wisconsin when the plane carrying him crashed into a lake on December 10, 1967. His final song – an unfinished version of "Sittin' On the Dock of the Bay" – became a massive hit after his death.

Influential producer Joe Meek committed murder

English producer, sound engineer, and songwriter Joe Meek was a key figure in 1960s music. He created the spacey sound effects used in many of the era's songs, pioneered studio recording techniques like overdubbing and spring reverb, helped found experimental pop, and became one of the first producers to be considered as essential to the music as the artists themselves. Over the course of his career, Meek produced hundreds of songs, including his most famous – 1962's "Telstar" – which became a hit for The Tornados.

Unfortunately, Meek's personal life was fraught with difficulty. As a gay man, he lived in constant fear since homosexuality was illegal in England at the time. In addition, he suffered from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia – neither of which was well understood or properly managed in the '60s. He was also a frequent recreational drug user.

Meek grew increasingly paranoid as the decade wore on. He became convinced that his colleagues were trying to steal his ideas, that everything from Buddy Holly's ghost to a purring cat was trying to send him important messages, and that aliens were controlling his mind. He also developed eccentric habits like attempting to commune with the dead. Meek's mental health crisis ultimately culminated in tragedy on February 3, 1967, when he shot and killed his landlady before dying by suicide.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Rock music became a white man's game

Becoming mainstream when Elvis Presley shook his hips in the 1950s, rock 'n' roll gained momentum throughout the '60s, fueled by British Invasion bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones as well as American groups like The Beach Boys and The Doors. There was just one problem: Mainstream rock stars were primarily white men, though the music had its roots in Black culture.

How this came to be is a matter of some debate. Many argue that the separation began in the '50s, with music industry executives not wanting to market Black music to white audiences. Others claim that Black artists segregated themselves by focusing on soul and R&B rather than rock. Still, as Jack Hamilton notes in his book "Just Around Midnight" (via Slate), artists like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan were admittedly heavily inspired by Black musicians like Chuck Berry and Muddy Waters.

Hamilton posits that the exclusion of Black artists from the evolving genre of rock in the '60s ultimately came down to systemic racism. Throughout the decade, Jimi Hendrix (pictured) was the only Black musician able to successfully break the barrier and he faced opposition from both the white and Black communities as a result. Women were similarly excluded from '60s rock, which frequently objectified them in its lyrics. Janis Joplin was one of the only women able to transcend this sexist gap and critics often reduced her to a novelty.

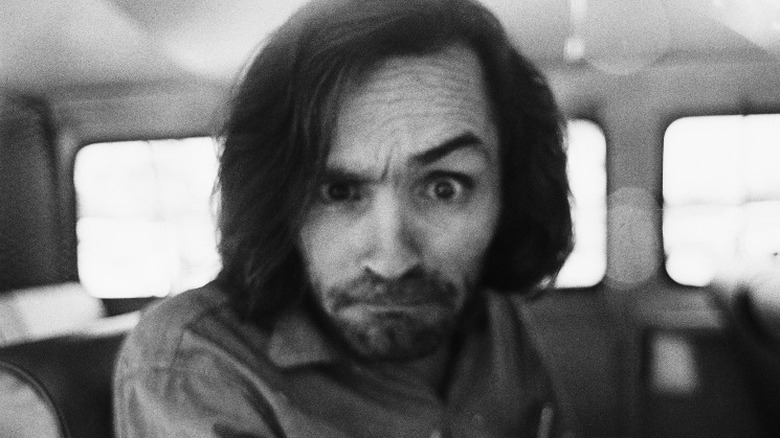

Charles Manson exposed the dark side of rock counterculture

While known to most as the leader of a cult that committed several horrific murders, Charles Manson was first an aspiring musician. A career criminal, he taught himself how to play guitar while serving time in prison. He then headed west to Los Angeles, California in 1967, where he befriended the likes of Neil Young and The Beach Boys' drummer Dennis Wilson.

In fact, Manson and Wilson became so close that they even lived together. The two also collaborated musically, with one of Manson's songs – "Cease to Exist" – giving rise to The Beach Boys' 1968 song "Never Learn Not to Love." It was a brief partnership, with Manson – angry that he wasn't credited – receiving a single payment for his contribution before being sent on his way.

Manson then became enamored with The Beatles' "White Album," listening to the songs obsessively until he became convinced that its lyrics included hidden messages about a coming race war. He encouraged his "family" – that is, his entourage of mostly female followers – to listen as well. This delusional fixation culminated in the brutal murders of nine people, including actress Sharon Tate, in 1969. At one of the crime scenes, a Manson follower had even written "Healter Skelter" – a reference to The Beatles' song "Helter Skelter" – in blood. Manson's first and only album, "LIE: The Love and Terror Cult," was released in 1970 while he and his followers awaited trial.

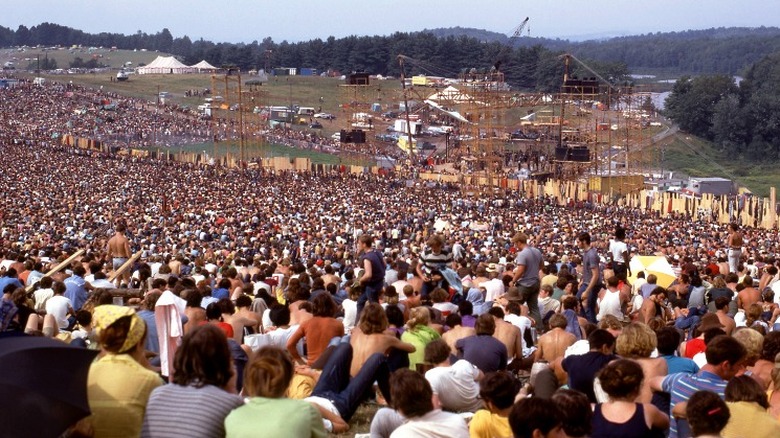

Woodstock was actually a logistical nightmare

Though Woodstock is applauded as one of history's most successful music festivals, in truth its promoters just got extremely lucky. Forced to find a new location just weeks before the event, many basic amenities went by the wayside. When August 1969 rolled around, some 300,000 people arrived in rural upstate New York to find limited bathrooms and inadequate supplies of food and water. What's worse, thunderstorms and heavy rainfall combined with shoddy electrical wiring and flimsy stage fixtures created a potentially dangerous situation, not to mention a muddy mess.

Woodstock's organizers were also completely unprepared for the event's high turnout. Roads were blocked for miles, meaning emergency supplies had to be delivered by air and many artists were unable to perform because they couldn't get to the location. Nearby hospitals also reached capacity and hungry attendees stripped adjacent corn crops, angering the area's farmers. In fact, the festival was made free simply because the outnumbered staff was unable to check tickets. The artists performed only to appease the masses.

While many concertgoers became ill and several overdosed on drugs, the festival was surprisingly incident-free – though one person was run over by a tractor and killed. "It probably should've been a disaster," Joel Makower – author of "Woodstock: The Oral History" – told the History Channel, adding, "The fact that it came off as well as it did is a minor miracle."

Concerts became increasingly dangerous

Despite the ongoing hippie movement, which promoted non-violence, attending concerts became increasingly hazardous in the 1960s. On March 1, 1967, Eric Burdon and The Animals refused to perform in Ottawa, Canada following a bungled negotiation with the venue's promoter. Fans, already gathered to enjoy the show, became enraged when the house lights came on instead, destroying the stage and starting fires. The violent outburst resulted in extensive damage and 12 arrests.

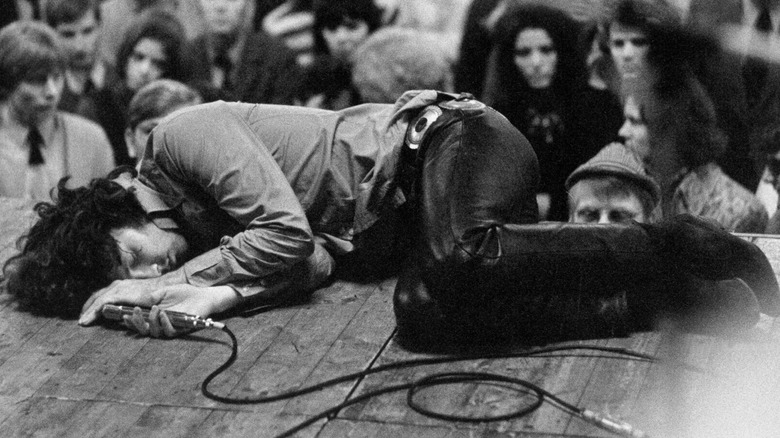

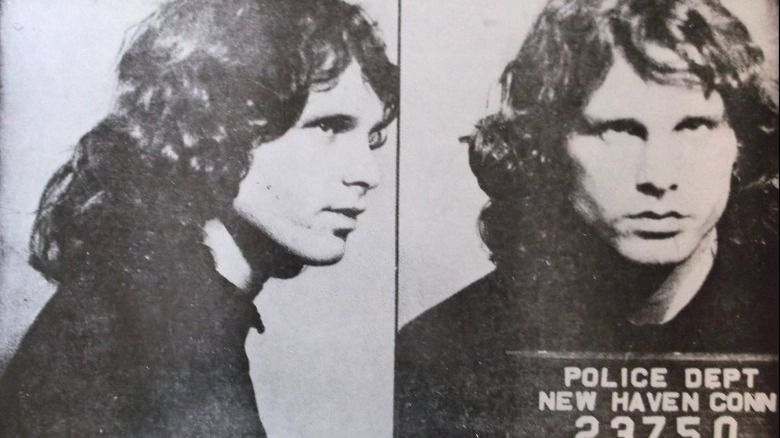

Then, on December 9, 1967, a Connecticut Doors concert spiraled out of control. Doors frontman Jim Morrison (pictured) was making out with a girl backstage when a police officer, not recognizing him, told them to leave. Morrison's snarky response didn't go over well and he ended up maced. Furious, he shared the incident with the audience, making several digs at the police. Officers quickly leaped on stage and arrested Morrison for inciting violence but angry fans wreaked such havoc that 13 additional arrests were made.

By far the decade's worst incident took place at the Altamont Free Festival on December 6, 1969. In a pinch due to lax planning, someone — it's not totally clear who — hired members of the Hells Angels – a well-known motorcycle gang – to work security at the event. Fueled by unchecked power and free beer, the bikers became violent. During Jefferson Airplane's performance, one of them attacked singer Marty Balin. Then, while The Rolling Stones played, Hells Angel Alan Passaro stabbed 18-year-old Meredith Hunter to death mere feet from the stage.

Substance abuse took a major toll

"Sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll" was the central ethos of 1960s counterculture. Substances like LSD, marijuana, heroin, and alcohol were heavily consumed by musicians and fans alike throughout the decade. In fact, drug use was even encouraged to promote the creation and enjoyment of good music.

Hallucinogenic substances like LSD – heavily promoted at the time – and marijuana especially were said to expand the mind and provide a means of understanding the world on a deeper level. They became firmly entrenched with '60s music, particularly the then-newly formed genre of psychedelic rock, which was characterized by swirling music that mimicked the experience of a drug trip.

But such wanton use took its toll. Syd Barrett – the founding member of Pink Floyd – broke from reality after overusing LSD and became unable to perform. Prolonged use of drugs and alcohol also claimed the lives of many. Virtuoso guitarist Jimi Hendrix, blues singer Janis Joplin (pictured), R&B singer-songwriter Frankie Lymon, and Beatles manager Brian Epstein were just a few of the '60s music legends who died of complications related to substance use at startlingly young ages.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).