The Messed Up Truth About The 2010s Music Industry

While 2019 might seem like yesterday for some, the music industry changed so much in the 2010s that the decade might as well have happened eons ago. As the BBC notes, many of the transformations were positive: Beyoncé released her surprise album "Lemonade" — a celebration of Black lives everywhere — SoundCloud and social media gave independent artists like Billie Eilish and XXXTentacion a voice, and music became more connected, with artists like Korean rapper Psy, and Puerto Rico's Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee, becoming worldwide sensations with their respective songs "Gangnam Style" and "Despacito."

Across the board, artists increasingly used their platforms to promote social and political change, encouraging their fans to fight against injustice. According to Pitchfork, Usher's 2015 song "Chains" criticized gun violence, racism, and police brutality through its interactive music video, Frank Ocean became an icon for the LGBTQ+ community by publicly coming out, and R&B artist Erykah Badu made "staying woke" a household term.

It was a time of relative freedom: Anyone with an internet connection could release music without the oversight of a record label or even a physical release, meaning artists no longer had to play by the rules. But corporate greed still abided — in the absence of record sales, the music industry turned its attention to live music and streaming platforms to boost its wealth, and both artists and fans suffered as a result. From festivals gone wrong to rampant misogyny to unregulated monopolies, here is the messed up truth about the 2010s music industry.

Streaming led to huge industry profits but stiffed artists

Digital downloads were all the rage when the decade began, but the era of carefully-curated iPods and MP3s was short-lived. According to The New York Times, everything changed in 2011 when Spotify launched in the United States, making it possible to stream songs using the internet and negating the need to own music at all. Other streaming services like Apple Music, Deezer, and TIDAL soon followed.

For a relatively small monthly fee, such platforms allowed users to listen to thousands of songs using a computer or smartphone — a deal so convenient and compelling that it even convinced people to pay for music again. Per the RIAA, streaming brought in 80% of the music industry's revenue by the end of 2019, saving it from the major profit losses it had experienced in the 2000s. There was just one problem: Very little of that money made it to the artists who created the music.

According to Digital Music News, one Spotify stream earns between $0.00121 and $0.00653 — mere fractions of pennies. To make matters worse, The Guardian notes that record labels take 50% of these earnings, the streaming platform takes 30%, and artists are left with a portion of the remaining 20%. For this reason, Taylor Swift removed her entire catalog from Spotify in late 2014 — with Spotify having to break the news (via Time) – having earlier written in a Wall Street Journal op-ed piece: "Music is art, and art is important and rare. Important, rare things are valuable. Valuable things should be paid for."

Coachella became an event primarily for the wealthy

The world-famous Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival was once a small, affordable affair. As The New Yorker notes, Coachella was inspired by a 1993 Pearl Jam show at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, California. The grunge band played the remote location to avoid supporting venues that used Ticketmaster, demonstrating its suitability for concerts. According to Rolling Stone, the first Coachella was held there in October 1999. It spanned two days, hosted artists from Rage Against the Machine to Morrissey, offered free parking, and cost just $50 per day.

Coachella quickly gained popularity, particularly with millennials, and throughout the 2000s, it grew to a yearly two-weekend, three-day festival attended by thousands each April (per CNN Money). But, according to The Los Angeles Times' music blog "Pop & Hiss," the affordable option for $99 single-day tickets disappeared in 2010, forcing concert-goers to shell out $269 plus fees for a three-day pass.

By the decade's end in 2019, Desert Sun notes that general admission for Coachella had soared to $429, with VIP passes available for $999. A shuttle ride from LAX to the remote location ran $75 one way, parking and camping passes for those unable to secure limited (and also costly) nearby hotels added an additional $125 to $325, and on-site tents ranged from $2,458 up to $9,500 for the most luxurious option. After food, drinks, and merchandise were considered, even the most frugal attendees paid thousands of dollars for one weekend.

Ticketmaster launched dynamic pricing for concert tickets

Ticketmaster has been a controversial company for decades. According to The Los Angeles Times, Pearl Jam lodged a complaint against the ticket agency with the United States Justice Department in 1994, claiming it had intentionally hindered the band's low-cost tour. They cited its hefty add-on fees, anti-competitive practices, and monopoly over ticket sales as problematic.

But Ticketmaster's power only increased. As The New Republic notes, the ticketing giant merged with the promotion company Live Nation — which, per The Guardian, managed artists and owned over 140 venues — in 2010, further increasing Ticketmaster's chokehold on live music. Per USA Today, Ticketmaster began implementing dynamic pricing for concerts in 2011 to combat scalpers. According to Rolling Stone, dynamic pricing causes ticket prices to change constantly to fit market demand rather than remaining at a fixed price point, similar to airline tickets.

In situations where demand is high, prices quickly become astronomical. Such was the case in 2018 when people attempted to purchase tickets for Taylor Swift's "Reputation" tour. Swift had opted to use dynamic pricing, meaning costs of coveted seats skyrocketed before fluctuating between $595 and $995. Fans were left frustrated, often paying hundreds of dollars over perceived face value for tickets, and many individuals in the concert business observed that Ticketmaster had essentially become the ultimate scalper. Indeed, Live Nation Entertainment saw steady increases in revenue throughout the decade, peaking at $11.55 billion in 2019, with $1.54 billion of this from ticket sales (per Statista).

One of the decade's biggest songs was problematic on many levels

In 2013, Robin Thicke, T.I., and Pharrell Williams' party anthem "Blurred Lines" completely took over the airwaves. According to Us Weekly, the catchy song led the Billboard Hot 100 chart for 12 straight weeks, received several Grammy nominations, and was later certified diamond, making it one of the most successful songs of the decade. But not everyone was a fan. Almost immediately, the song drew controversy for its problematic lyrics like "I know you want it" and "I hate these blurred lines."

As The Guardian notes, several U.K. universities banned the song, claiming it objectified women, disregarded the need for consent, and even promoted rape. The song's misogynistic music video didn't help. Per Billboard, the unrated version, which featured Thicke, Williams, and T.I. — all fully clothed — surrounded by nude models, was banned by YouTube. And, as it turned out, life imitated art. In her 2021 book "My Body" (via The Times), model Emily Ratajkowski claimed that Thicke groped her breasts during the video's filming, stating that the incident humiliated her and made her feel "naked for the first time that day."

Thicke and Williams were also accused of copyright infringement. According to Forbes, Marvin Gaye's family claimed that "Blurred Lines" was remarkably similar to Gaye's 1977 hit "Got to Give it Up." This led to a five-year legal battle which, per Rolling Stone, ultimately culminated in Thicke and Williams paying Gaye's family around $5 million in 2018.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Chart trickery became commonplace

With digital music and streaming now the dominant forms of music consumption, artists and labels quickly found new ways to manipulate the system in their favor. As Slate notes, it started in 2014 when Apple gifted everyone a copy of U2's latest album, "Songs of Innocence," against their will. While it might have seemed harmless, Apple had essentially purchased millions of copies of the album and added it to all of its user's iTunes libraries, giving it more album sales than it likely would have had.

Similar shenanigans continued throughout the decade. As announced by Billboard, the music industry started measuring success in album-equivalent units in the mid-2010s to account for digital downloads and streaming. The RIAA, for example, considers 1,500 streams equal to one album sale. Some artists took this information in stride. As Vulture notes, Chris Brown's 2017 album "Heartbreak on a Full Moon" featured a whopping 40 songs, likely to garner more streams. Brown's tactic worked — per Billboard, it reached number one on the Top Hip-Hop/R&B Albums chart that year.

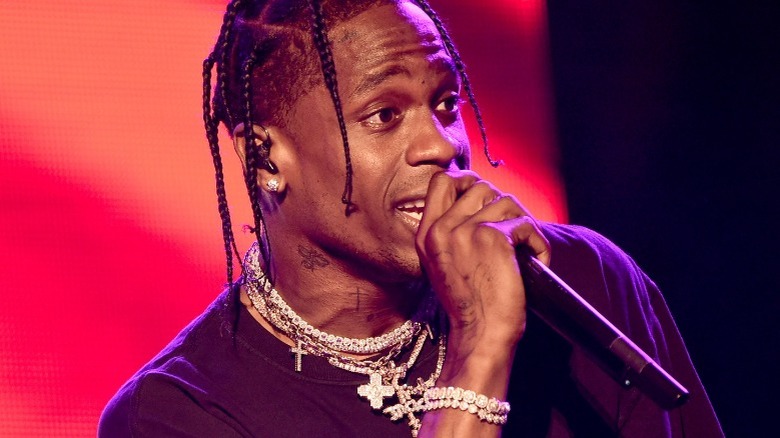

Bundling was another effective strategy to inflate sales figures. According to Fader, rapper Travis Scott racked up thousands of album sales by pairing a digital download of his 2018 album "ASTROWORLD" with exclusive merchandise items, like limited edition t-shirts and presale codes for his upcoming shows. Desperate to collect them all, his fans bought thousands of copies of "ASTROWORLD," powering it all the way to the top of the charts.

Several terrorist attacks targeted concerts

The 2010s saw several horrific attacks on concertgoers. According to the BBC, three men — later revealed to be Islamic terrorists — entered the Bataclan theater in Paris, France, during an Eagles of Death Metal show on November 13, 2015, and fired on the 1,500-person crowd with assault rifles, killing 90 people and injuring many others. Several concertgoers managed to escape through a side exit, a few climbed onto the roof, and others lay on the ground. The shooting — part of an organized citywide attack — ended with the three perpetrators being shot or exploding their suicide belts.

Tragedy struck again a few years later. As History notes, a radicalized suicide bomber detonated himself immediately following an Ariana Grande concert at England's Manchester Arena on May 22, 2017, killing 22 concertgoers and injuring 116 more. Per Rolling Stone, on October 1 that same year, a lone gunman fired into the crowd of Las Vegas' Route 91 country music festival from his adjacent hotel room, killing 58 and injuring over 500.

The devastating attacks have impacted live music enthusiasts the world over. According to a 2015 survey by SpinGo (via Business Wire), one in three Americans felt concerned for their safety while attending live music events following the Paris attack, with over half of those surveyed expressing a need for increased concert security. As research firm Ovum's Simon Dyson told CNBC, such security measures will likely further increase ticket prices as venues, promoters, and artists reallocate their resources.

If you have been impacted by incidents of mass violence, or are experiencing emotional distress related to incidents of mass violence, you can call or text Disaster Distress Helpline at 1-800-985-5990 for support.

Fyre Festival was a complete disaster

Conceived by entrepreneur Billy MacFarland and rapper Ja Rule, 2017's Fyre Festival was supposed to be the greatest live music event of all time. According to CNBC, the pair promised an island getaway in the Bahamas, complete with fine dining, luxurious lodging, and performances by top acts like Migos and Blink-182. Following heavy promotion on social media — namely videos peppered with models lounging on the beach — the anticipation was so great that people paid up to $49,000 for tickets.

But when April 2017 rolled around, Fyre ticket holders were met with a very different experience. According to the BBC, excited festivalgoers arrived on the island of Great Exuma to find wet mattresses on the ground, disaster tents for lodging, and general chaos. Luggage was dispensed from a shipping container and attendees were left to fend for themselves, with most immediately seeking the next flight off the island.

Trevor DeHaas' tweet featuring a now-iconic picture of an uninspiring cheese sandwich — served in place of the five-star catering that festival promoters had promised — concisely summarized the catastrophe. Blink-182 also took to Twitter amidst the turmoil to cancel their performances, stating that they did not think they would have what they needed to put on good shows. Per NBC News, MacFarland pleaded guilty to wire fraud in 2018 and was ordered to pay back everyone he had conned into investing in his various schemes — a sum totaling $26 million. He was also sentenced to six years in federal prison.

Misogyny was still rampant in the music industry

Female artists continued to navigate misogyny in the music industry in the 2010s. Perhaps the decade's most famous instance of such injustice was pop star Kesha's long legal battle with her producer, Dr. Luke. According to Billboard, Kesha entered into a six-album deal with Luke in 2005, when she was 18. The two released her 2010 album "Animal" — which featured her breakout song "TiK ToK" — together.

In 2014, Kesha filed a lawsuit against Luke, claiming that he had bullied her about her weight, was consistently emotionally abusive, and had threatened to ruin her career if she didn't comply with him. She also claimed that in 2005, Luke drugged her at a party and took her back to his hotel room, where he raped her while she was unconscious. Luke countersued for defamation.

In 2016, a judge denied a preliminary injunction that would have released Kesha from her contract, leaving her in tears. Her mother, Pebe Sebert, told Billboard: "Dr. Luke basically owns Kesha until her death ... She can't legally put any new music out, or he can and will sue her." Other female artists — including Adele, Lady Gaga, and Kelly Clarkson — rallied behind Kesha. Taylor Swift even sent her $250,000 to assist with legal fees. As CBS News notes, Swift had fought her own legal battle against sexual abuse when a radio DJ groped her at a meet-and-greet in 2013, then sued her for losing his job. Swift successfully countersued for one dollar.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Sneakier versions of payola emerged

As online platforms replaced radio and music television, artists and record labels began searching for new ways to get heard. Naturally, money talked. According to a 2022 study published in UC Irvine Law Review, labels could pay for ads — which got songs played with higher frequency — petition Spotify editors to add their artists' songs to curated playlists streamed by millions, or pay third-party companies, like Playlist Push, to locate and pitch songs to popular playlist curators or influencers.

A successful playlister campaign typically costs about $500 to $1,500 per song. To ensure the job gets done, Playlist Push often pays up to $12 for the song's consideration or addition to a playlist. TikTok campaigns are a little cheaper: $300 gets a song added to a list that influencers can choose from. If the song is used in a TikTok video, Playlist Push pays the influencer $10.

According to Rolling Stone, Spotify's new promotional tool, Marquee, comes even closer to payola. Launched in 2019, Marquee presents pop-up ads that remind users of new songs and albums on their release day. Spotify requests a minimum of $5,000 per such campaign, charging 55 cents every time a user clicks on a pop-up. In exchange, it promises over 9,000 new listeners per week. Like radio payola, the system favors the already wealthy, which tend to be mainstream artists and major labels. But unlike radio stations, online platforms do not fall under the FCC's jurisdiction and remain unregulated.

Taylor Swift reminded the world that artists still didn't own their masters

In a 2018 press release, Universal Music Group announced that country singer-songwriter turned pop megastar Taylor Swift had signed a multi-album deal with UMG, the world's biggest label. Of course, this also meant that she had left her original indie label, Big Machine Records, behind. According to Time, a teenage Swift signed with Big Machine in 2005. She released her first six albums on the label, including 2012's "Red," 2014's "1989," and 2017's "Reputation."

Shortly after Swift's departure, Big Machine Records — along with all of Swift's masters — was sold to Ithaca Holdings, a company owned by Swift's longtime rival, Scooter Braun. Swift took to Tumblr to express her disappointment in 2019, writing: "For years I asked, pleaded for a chance to own my own work. Instead, I was given an opportunity to sign back up to Big Machine Records ... I had to make the excruciating choice to leave behind my past."

Swift claims that Big Machine's founder, Scott Borchetta, sold her masters to Braun out of spite, although Borchetta denies this. In a blog post on Big Machine Label Group, he claims that Swift had willingly surrendered her masters. Nonetheless, Swift set to work re-recording her first six albums, encouraging her fans to purchase and stream "Taylor's Versions" of her songs to reclaim rights and ensure that royalties did not end up benefiting Braun (per Time). As she wrote on Tumblr, "You deserve to own the art you make."

The music industry continued to profit off Michael Jackson

In 2019, 10 years after Michael Jackson's death, HBO released "Leaving Neverland," a four-hour documentary showcasing the struggles of Jackson's now-grown victims Wade Robson and James Safechuck (per Rolling Stone). According to the documentary (via Rolling Stone), Jackson groomed and later sexually abused both men when they were children. It wasn't the first time the King of Pop had faced such accusations: Jackson was arrested for child molestation in 2003, but was later acquitted following a 2005 trial. And, per Money, he had settled earlier child abuse accusations out of court in the 1990s.

In light of the #MeToo movement and docuseries "Surviving R. Kelly," which saw the singer dropped from his record label, Jackson's fans had to question if separating the art from the artist was still a viable option. A few took action: Radio stations in Canada and New Zealand boycotted his music, the Children's Museum of Indianapolis removed his gloves and fedora from display, and the producer of "The Simpsons" pulled his 1991 episode.

But for the most part, Jackson's legacy was unscathed. Spotify and Apple Music did not pull his music, and his streaming numbers remained high. According to Forbes, Jackson's estate — which vehemently denies "Leaving Neverland's" accusations and even sued HBO over it (per Rolling Stone) — has made $2 billion since his death, meaning the music industry continues to profit off Jackson. In fact, according to Forbes, his U.S. streams increased from 1.8 to 2.1 billion in 2019.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Pop songs became increasingly formulaic

Popular music became more formulaic than ever in the 2010s. For starters, Quartz notes that songs lost about 20 seconds from 2013 to 2018, with 6% of 2018's hit songs coming in at two minutes and thirty seconds or less. This is likely the fault of streaming: Since artists earn money for complete streams and the pay rate for every song is the same regardless of length, shorter songs allow artists to rack up more streams and therefore maximize profits. This monetary incentive affected everyone from rapper Kanye West to country singer Jason Aldean, and indeed both artists released increasingly shorter songs over the decade.

In addition, most of the top charting songs in the 2010s were actually written by the same handful of people. According to Billboard, Swedish record producer Max Martin (pictured) wrote 16 of the decade's Billboard Hot 100 number one songs, including Katy Perry's "California Gurls," P!nk's "Raise Your Glass," Taylor Swift's "Shake It Off," and The Weeknd's "Can't Feel My Face." Per Rolling Stone, OneRepublic's Ryan Tedder also wrote quite a few of the 2010s' biggest hits, including Adele's "Rumour Has It" and Ellie Goulding's "Burn." And, as Time notes, pop star Sia had a hand in the behind-the-scenes hit-making as well, writing Beyoncé's "Pretty Hurts" and Rihanna's "Diamonds," among many others. All of this culminated in a decade of songs that sounded eerily similar.

Unregulated monopolies dominated every aspect of music

Music industry monopolies really started flexing their power in the 2010s and aren't likely to relent any time soon. With its near complete control over ticket-selling technology, venues, promotion, and major artists, Live Nation Entertainment — formed from Live Nation and Ticketmaster — had tremendous power over live music — capable of putting rival venues out of business, charging increasingly outrageous service fees, and cutting off anyone willing to oppose its practices (per The Arts Fuse). According to The New York Times, Live Nation promoted over 30,000 shows, sold around 500 million tickets, and controlled over 200 venues in 2018.

Similarly, Wired notes that three major record labels — Sony, Universal, and Warner Music — dominated the music industry throughout the decade, determining which artists got played on the radio, streamed, promoted, or signed at all. This control is evident in the decade's hits: 90% of the 2010s' top 10 songs were by artists on major labels. Diversity plummeted as few new songs even made it to the charts. It's the same in streaming: Two platforms, Spotify and YouTube, grew to host 75% of the world's streams, and, as the next decade dawned, Spotify started leveraging its power over labels and artists to demand higher fees and royalty portions, in exchange for reach.

Unchecked consolidation over the 2010s has given a select few companies control over every aspect of today's music, and, as Newsweek notes, at the top of it all sits one billionaire: John Malone (pictured), who owns large portions of Live Nation, Pandora, SiriusXM, and iHeartRadio — a massive swath of the music industry.