A Complete Timeline Of Ticketmaster's Rise To Power

Ticketmaster. The very name strikes fury and anxiety into the hearts of many. While, per Wired, it was once just a clever computer inventory system created to efficiently sell local event tickets, Ticketmaster has since grown to become a household name – and not for good reasons. One of the public's main grievances against the ticketing company is its excessive service fees, often tacked on at the last second before purchase. Such extra charges started in the 1980s, though they usually capped out at around $1.50 tops (per The Chicago Tribune).

But Ticketmaster's fees gradually increased over time and were a major driver of the company's success. Still, former Ticketmaster CEO Fred Rosen told Artists House Music in 2006 that "nobody paid more for a ticket than they wanted to," adding, "it wasn't like you had a $50 ticket and a $25 service charge." Yet, just a few years later, that's pretty much exactly what you had – only worse. According to More Perfect Union, service fees amount to a shocking 78% of the price of a ticket as of 2022.

Per USA Today, the company introduced demand-based dynamic pricing in 2011, further increasing both ticket prices and controversy surrounding the company. By 2019, Live Nation Entertainment – which owns Ticketmaster – reported $11.5 billion in revenue, with $1.54 billion of this from ticket sales alone. So how did a ticketing system designed to make our lives more convenient become yet another financial burden? Here is a complete timeline of Ticketmaster's rise to power.

Ticketmaster was started by university employees in 1976

Ticketmaster had relatively innocent beginnings. According to Wired, it all started at Arizona State University in 1976, when Peter Gadwa, an employee of ASU's IT department, joined forces with Albert Leffler, who worked at the college's performing arts center. The pair started by successfully creating a better local ticketing system for the university's theater. Per Ticketmaster's website, they were soon joined by businessman Gordon Gunn III. Leffler coined the new company's name – Ticketmaster – and they were off.

As The Los Angeles Times notes, Gadwa was a skilled computer programmer and Leffler was an event booking specialist. Together, they created and licensed ticket-selling computer programs and sold them to other cities. They also handled tickets for their first major concert – a New Mexico Electric Light Orchestra show – in 1977 (per Ticketmaster). The pair continued to work towards creating a more efficient computerized system for selling tickets.

According to Encyclopedia.com, Ticketmaster's big breakthrough came in 1978 when its founders created a computer network that enabled them to view all inventory for a show rather than just isolated individual vendor allotments. This allowed people to select the best available seats at any given time and completely changed event ticketing forever. By 1981, Ticketmaster had earned $1 million – but a bigger ticketing company called Ticketron still dominated the industry.

Ticketmaster allied itself with concert promoters and venues

According to Encyclopedia.com, investor Jay Pritzker – the owner of Hyatt hotels – purchased Ticketmaster for $4 million in 1982. He then appointed stand-up-comedian-turned-lawyer Fred Rosen (pictured) as the CEO. Rosen aggressively focused his attention on the concert industry, confident that if a fan wanted to see a show bad enough, they would pay anything for a ticket.

As Encyclopedia.com notes, artists had become increasingly demanding in the 1970s and early '80s, often taking the majority of concert earnings and leaving the promoters and venues very little. Rosen used these frustrations to his advantage. According to Wired, he began contacting venues immediately, offering them a screaming deal. While competitor Ticketron charged them to sell tickets, Rosen promised to pay them. What's more, tickets would be sold more efficiently using Ticketmaster's innovative new program rather than the venue's box office. Venues signed up in droves, dropping Ticketron like a bad habit.

But exactly how did Rosen uphold this seemingly impossible deal? Enter the ticket service fee. Rather than charging the venue to sell tickets, Rosen charged the consumer and split the earnings with the venue and promoters (per Encyclopedia.com). He justified the fee, claiming he offered ticket buyers convenience – by using Ticketmaster's state-of-the-art computerized system (then accessed via phone operator), buyers could avoid having to line up at box offices and outlets. In a 2006 interview with Artists House Music, Rosen stated: "We served the public. But our clients were the venues and the promoters."

Ticketmaster defeated its main rival

In a 2006 interview with Artists House Music, former Ticketmaster CEO Fred Rosen recalled, "I wanted to sell every ticket in America." But he had competition. Per Encyclopedia.com, Ticketmaster's main rival was Ticketron, a ticketing agency that had dominated the industry for decades. Venues did business with Ticketron simply because there was no better option. But, as Rosen explained, the company had major shortcomings. For one, he claimed that venues were frustrated with Ticketron's endless excuses, old machines, lack of innovation, and overall bad service. Second, Ticketron charged them for the pleasure.

When Rosen started paying venues in the early 1980s, the decision to switch to Ticketmaster was nearly unanimous. According to The Washington Post, Ticketron eventually started playing the same game and charging their own service fees. The two companies battled it out for a decade, with Ticketron's owner, Abe Pollin (pictured), even publicly feuding with and suing Rosen. The battle ended in 1991 when Ticketmaster acquired Ticketron in a merger.

At the time, Ticketron's president claimed that merging would lower service fees, as the lack of competition would allow for less expensive deals with promoters. But prior to the union, Ticketron officials had expressed concerns with Ticketmaster's growing dominance, claiming that a single ticketing service would have little incentive to keep fees low. During his 1989 lawsuit against Rosen, Pollin even said, "There is certainly enough room for two major companies in this business. Competition made this country great."

Pearl Jam fought back against Ticketmaster but no one listened

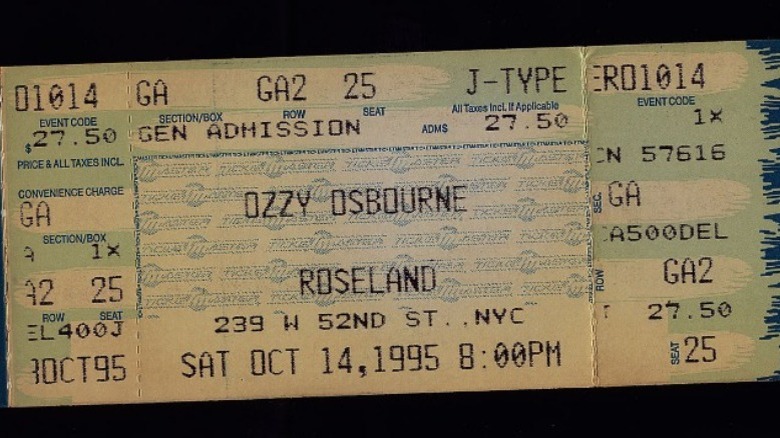

Ticketmaster really began flexing its power in the 1990s. According to Rolling Stone, the popular grunge band Pearl Jam went head-to-head with the ticketing giant in 1994 while planning their much-anticipated 1995 tour. The group requested that ticket prices be kept at $18, including only a reasonable service fee of $1.80 that was fully disclosed to buyers. Naturally, Ticketmaster – accustomed to charging fees of $3.60 to $18 by the mid-'90s – refused, and Pearl Jam called off the tour.

Shortly after, the United States Department of Justice approached the band and convinced them to file an antitrust complaint against Ticketmaster. Pearl Jam complied, claiming that the company's high fees and exclusive paid arrangements with venues were a clear abuse of monopolistic power that left artists and fans with no other options. While awaiting the Justice Department's verdict, Pearl Jam embarked on a calamitous tour of the nation's fairgrounds and remote parks, unable to play in most venues as they fell under Ticketmaster's purview.

In the end, nothing came of the band's great efforts. Other artists were hesitant to rally behind Pearl Jam, especially after witnessing how being exiled from major venues had impacted their tour. In the end, the Department of Justice quietly concluded its investigation, a bill proposing that Ticketmaster clearly disclose its service fees was dismissed, and Ticketmaster continued its practices unhindered. Meanwhile, the debacle cost Pearl Jam around $2 million (per Far Out Magazine).

Ticketmaster started selling tickets online

1996 was a big year for Ticketmaster. As The Los Angeles Times notes, the company – recently purchased by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen (pictured) – went public. At the time, Ticketmaster earned an average of $3.50 on every ticket sold, but concert attendance had decreased. It seemed that the public was getting wise to the company's fees. Still, tech guru Allen had high hopes for Ticketmaster, including plans to venture into amusement parks, zoos, and overseas markets.

Then came more exciting news. According to Dan Schiller in his book "Digital Capitalism," Ticketmaster sold its first online ticket – for a Seattle Mariners game, as per Ticketmaster – in November 1996. As then-CEO Fred Rosen told Artists House Music in 2006, the news was underwhelming at the time. Still, Rosen asked his employees to find out what motivated the buyer to use the internet rather than the phone system to purchase his ticket. According to Rosen, the man's response when they finally got ahold of him was: "I don't like talking to people and I don't like talking to you."

E-commerce redefined consumer convenience and opened a whole new market. Rosen notes that in the first full month, Ticketmaster made $100,000 off online ticket sales. By the second month, that figure had grown to $1 million and by month three, it was $3 million. Per CNN Money, the company was processing 75,000 online ticket transactions daily and earning $7.5 million monthly by March 1998. The internet age had arrived.

Consumers unsuccessfully sued Ticketmaster for high fees

As Ticketmaster's profits grew, so did consumers' frustrations. According to the United States Department of Justice, a group of angry ticket buyers led by Alex Campos filed a lawsuit against Ticketmaster in 1998, citing high service and handling fees made possible by the company's monopoly of ticket sales and venues. Per CBS News, Ticketmaster's add-on fees had reached up to $20 per ticket by 1998.

The consumers sought triple antitrust damages for the high fees they had paid and requested a court order that would stop Ticketmaster from future abusive charges. According to The Los Angeles Times, Ticketmaster officials contacted a federal judge and pleaded the company's case, claiming that the venues were its clients, not the ticket buyers. Under existing antitrust law, this meant that consumers were "indirect purchasers" and were therefore not able to sue Ticketmaster as the seller. Only "direct purchasers" – in this case, the venues – had legal grounds to sue for price-fixing.

But, as CBS News notes, venues benefitted greatly from their arrangement with Ticketmaster and therefore had no incentive to ever pursue such charges. Ultimately, the United States Supreme Court rejected the consumers' appeal without comment in 1999, siding with Ticketmaster and rendering the company immune from all similar lawsuits.

Ticketmaster joined forces with Front Line Management

The internet took a greater hold over society in the 2000s. According to The Berkeley Beacon, illegal filesharing and digital music decimated music industry profits. Faced with declining record sales, several companies began focusing their efforts on live music for financial gains. By far the most successful of these ventures was Live Nation. As Reuters notes, Live Nation started as a concert promotion company but gradually grew to own hundreds of venues, including the House of Blues chain. In the absence of conventional record deals, Live Nation also started making exclusive arrangements with prominent artists like Madonna, Jay-Z, and U2.

Fast becoming a music industry superpower, Live Nation inevitably began attempting to conquer its final frontier: ticketing. Per Wired, Live Nation CEO Michael Rapino (pictured) started working with CTS Eventim, a German ticketing company, to develop its own ticketing system in 2007. Naturally, Ticketmaster – which had dominated ticket sales for over a decade – took immediate notice of its new competitor.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the ticketing giant purchased its own promotional company – Front Line Management – in what many believe was a counterstrike against Live Nation. At the time, Front Line Management was the biggest talent management company in the world, handling the careers of The Eagles, Christina Aguilera, and Jimmy Buffett, among many others. In its new incarnation as Ticketmaster Entertainment, the company could use its affiliations with major artists as additional clout when vying for favor with venues.

Bruce Springsteen condemned Ticketmaster's shady practices

Many fans using Ticketmaster to buy tickets to Bruce Springsteen's "Working on a Dream" tour in 2009 were met with a most unpleasant surprise. According to Rolling Stone, buyers not sidelined with rampant technical difficulties were secretly re-routed to Ticketmaster's secondary market site, TicketsNow, where they were tricked into spending significantly more for upsold tickets still available at face value on the main site.

Springsteen was livid. In response, he penned a letter to Ticketmaster on his website, denouncing the company's sneaky move, assuring fans he was not in an exclusive arrangement with Ticketmaster and had no knowledge of its secondary market dealings, and encouraging consumers to write to their representatives to oppose the company's monopolistic abuse. He concluded his letter by stating (via Rolling Stone): "The one thing that would make the current ticket situation even worse for the fan than it is now would be Ticketmaster and Live Nation coming up with a single system, thereby returning us to a near monopoly situation in music ticketing."

According to NJ.com, the resulting outrage caused the then-New Jersey attorney general to file a complaint against Ticketmaster, which resulted in a Federal Trade Commission investigation. In addition, a U.S. representative initiated legislation – termed the BOSS Act – that sought better regulations for the ticket industry. Fans also sued Ticketmaster for its deceptive practices. In 2011, Ticketmaster settled the lawsuit for $16.5 million but ultimately suffered no other consequences for its actions.

Ticketmaster merged with Live Nation

Despite widespread trepidations among fans and artists – including some harsh words from rocker Bruce Springsteen – Ticketmaster and Live Nation ended their several-year competition and began working together in 2009. As Reuters notes, the United States Department of Justice approved a merger between the two companies in early 2010, creating the industry giant now known as Live Nation Entertainment.

The merger married Ticketmaster Entertainment – dominant ticket-seller and owner of Front Line Management – with Live Nation, the world's largest concert promotion company, owner of hundreds of venues, and manager of countless artists. At the time, this gave one company complete dominion over every aspect of more than 140 million tickets, 140 venues, and 22,000 concerts each year. As a condition of approval, the Justice Department required Ticketmaster to sell parts of its company to create opportunities for rivals. Live Nation Entertainment also had to agree not to engage in any anticompetitive abuses of its power. The arrangement was set for ten years.

Christine Varney, the then-head of the U.S. Justice Department's Antitrust Division, even claimed that she expected ticket prices to decrease as a result of the union. But fans, lawmakers, would-be competitors, and artists were not convinced. Though they claimed to be exaggerating at the time, a writer for The Berkeley Beacon described the merger thusly: "Price gouging of epic proportions could occur, leaving the world of live music a post-apocalyptic, totalitarian wasteland ruled by one omnipotent corporation." Sadly, it wasn't too far from the truth.

Consumers successfully sued Ticketmaster for deceptive fees

Sometimes the legal process just takes time. According to Billboard, five ticket buyers sued Ticketmaster for deceptive ticket fees way back in 2003, when online ticket selling was in its infancy. The buyers had noticed that Ticketmaster was still charging order processing and UPS delivery fees even though physical tickets were no longer mailed. An investigation revealed that Ticketmaster was not actually doing any processing or delivering, but was still pocketing the money.

In 2014, the settlement was estimated to be in the ballpark of $400 million, covering around 50 million people who were wrongfully charged when they purchased Ticketmaster tickets between October 21, 1999, and February 27, 2013. Per CNN Money, the customers were finally offered a measure of closure in the case thirteen years later when Live Nation Entertainment – while never actually admitting any wrongdoing – agreed to a $45 million settlement, some of it dispensed in the form of discounts and free ticket vouchers in June 2016.

Live Nation staff made it abundantly clear that such credits did not apply to all shows, repeatedly stating on their website: "This voucher is potentially redeemable for two eligible General Admission tickets for certain Live Nation concert events subject to availability and limitations." They also stressed that vouchers were only available on a first-come, first-served basis. Indeed, a nationwide investigation of 70 U.S. cities by NBC's 13 WTHR failed to locate a single eligible concert in March 2017.

Ticketmaster teamed up with scalpers

According to The Hollywood Reporter, Ticketmaster sued Prestige Entertainment and others for using online bots to buy up tons of event tickets in 2017, citing a pretty clear violation of copyright acts and anti-scalping laws. So, imagine everyone's surprise when Prestige Entertainment clapped back by alleging that Ticketmaster was guilty of the same crime, using its own bots to buy up large volumes of tickets for later resale at inflated prices (per The Hollywood Reporter).

The plot thickened when CBC did an undercover investigation at a Las Vegas ticketing and entertainment summit in 2018. Posing as professional scalpers, reporters infiltrated Ticketmaster's secret inner workings with hidden cameras. They captured footage of Ticketmaster recruiters explaining in detail how their secondary market program worked – most importantly, how they never prosecuted those who used bots or fake names to scoop up tickets. In fact, they facilitated scalpers by allowing them to resell tickets on their site using a program called TradeDesk. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement, as Ticketmaster was then able to charge service fees twice on the same ticket.

Outraged by the scandal, fans initiated yet another class action lawsuit against Ticketmaster, this time for "unlawful and unfair business practices" (per Rolling Stone). But Ticketmaster managed to escape litigation yet again. According to Law360 (via Digital Music News), the company successfully argued that it cannot be sued by consumers and was granted a request to arbitrate the suit out of the public eye in 2019.

Ticketmaster consistently managed to escape serious penalties

Ticketmaster and its parent company Live Nation have been in hot water quite a few times. In addition to several consumer lawsuits – many of which are still pending as of 2022 – Live Nation has faced scrutiny from the United States Justice Department. According to court documents released in 2020 (via Rolling Stone), Live Nation had previously strong-armed six venues into exclusively using Ticketmaster, threatening to cut off concert business if they used a competitor. The misconduct dates all the way back to 2012.

As Reuters notes, Ticketmaster also faced criminal charges for repeatedly hacking competitor Songkick's data from 2013 to 2015 in an effort to destroy the company by poaching its clients. Ticketmaster paid a $10 million fine to avoid prosecution. Such behavior is the definition of anti-competitive, monopolistic abuse and demonstrates blatant and repeated violations of the consent decree Live Nation and Ticketmaster had agreed to when the merger was approved in 2010. But, right before the Justice Department finalized its lawsuit against the company, Live Nation settled.

In January 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice extended Live Nation Entertainment's consent decree by five years, stating, "Live Nation broke the promises they made to the court and the American people when they merged with Ticketmaster in 2010; today, we're holding them accountable." Per Rolling Stone, this meant stricter penalties and additional compliance monitoring, but many felt that it was a light slap on the wrist for a litany of serious transgressions.

More artists started using Ticketmaster's dynamic pricing

The beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was exceptionally hard on the live music industry. For a full year, artists, promoters, and venues watched their profits plummet to zero and Live Nation Entertainment reported a shocking 92% decline in revenue from 2019 to 2020 (per Rolling Stone). Luckily, when concerts finally resumed in 2021, Ticketmaster already had the perfect recovery strategy in place.

As USA Today notes, Ticketmaster introduced dynamic ticket pricing in 2011 to funnel money lost to scalpers back into the music industry. Per Rolling Stone, such pricing fluctuates to match market demand, similar to airline tickets. Ticketmaster allows artists to opt in or out of dynamic pricing as they see fit, with many, like The Foo Fighters, Father John Misty, and Pearl Jam, choosing to keep prices low for their fans. Taylor Swift was an early adopter of dynamic pricing, opting to use it when tickets for her 2018 "Reputation" tour went on sale. At the time, the high prices shocked fans: The same seat could cost $595 to $995, depending on when you looked.

Following the financially-devastating pandemic, more artists opted to use dynamic pricing, leading to the sky-high 2022 ticket prices that quickly became the new normal. Blink-182 tickets got up to $600 at some venues (per Billboard), and even Bruce Springsteen, who once opposed Ticketmaster, weathered his fans' wrath when he allowed his tickets to be dynamically priced, driving them up to $5,000 in some cases (per Rolling Stone).

Ticketmaster botched the presale for Taylor Swift's 'Eras' tour

According to The New York Times, 3.5 million Taylor Swift fans logged on to Ticketmaster to purchase presale tickets for Swift's "Eras" tour on November 15, 2022. Despite using its Verified Fan feature to minimize bots and lessen the burden on its systems, Ticketmaster was quickly overwhelmed. Fans often waited for hours in virtual rooms only to get booted mid-sale and lose their tickets. Per PopBuzz, those who succeeded paid anywhere from $49 to $449, while unlucky fans forced to resort to resale tickets faced mind-boggling prices of up to $33,000.

Ticketmaster sold over two million Swift tickets during the first presale alone (per The New York Times). Following the second presale, the company canceled the public sale due to low ticket inventory. Fans were outraged. Swift took to Instagram on November 18, stating in a story (via CNN), "It's really difficult for me to trust an outside entity with these relationships and loyalties, and excruciating for me to just watch mistakes happen with no recourse."

Accorded to Wired, Ticketmaster's lack of competition has likely led to its stagnation of technological innovation. Despite charging its customers outrageous service and convenience fees, the company frequently fails to actually provide either of these perks. While Ticketmaster apologized for the snafu, citing "unprecedented demand," the debacle drew attention to the growing problem of Ticketmaster's unchecked monopoly. Many are now imploring the current administration to focus its antitrust investigations on Live Nation Entertainment next.